This is the fifth post in a series commissioned for The Drawing Center that will expand on topics related to the exhibition Lebbeus Woods, Architect, which was on view in our Main Gallery from April 17th – June 15th, 2014. The form is inspired by Lebbeus’ own masterful and insightful blog which can be read here. The first four posts are available: here, here, here, and here.

James Lowder

THE STATE OF EDUCATING, THE SENSES

The name Lebbeus Woods has long been considered synonymous with the radical and the experimental within the discipline of architecture, his own personal form of architectural practice displaying at once a unique and singular vision through a range of exquisitely delineated drawings of unthinkable beauty. Much more than mere exercises in virtuosity, the often jarring yet captivating images he produced had the capacity to transform the very fabric of the known world and transport the viewer into spaces never before conceived, representations that had profound political repercussions beyond any building he could make, and a critical architecture that questioned the fundamental definitions of the practice and the social and cultural role of the architect. He was the real deal, and his relentless and authentic commitment to a radical agenda had a profound effect on the discipline. What is perhaps less well known is how this radical and anarchic position was equally characteristic of Lebbeus as an educator.

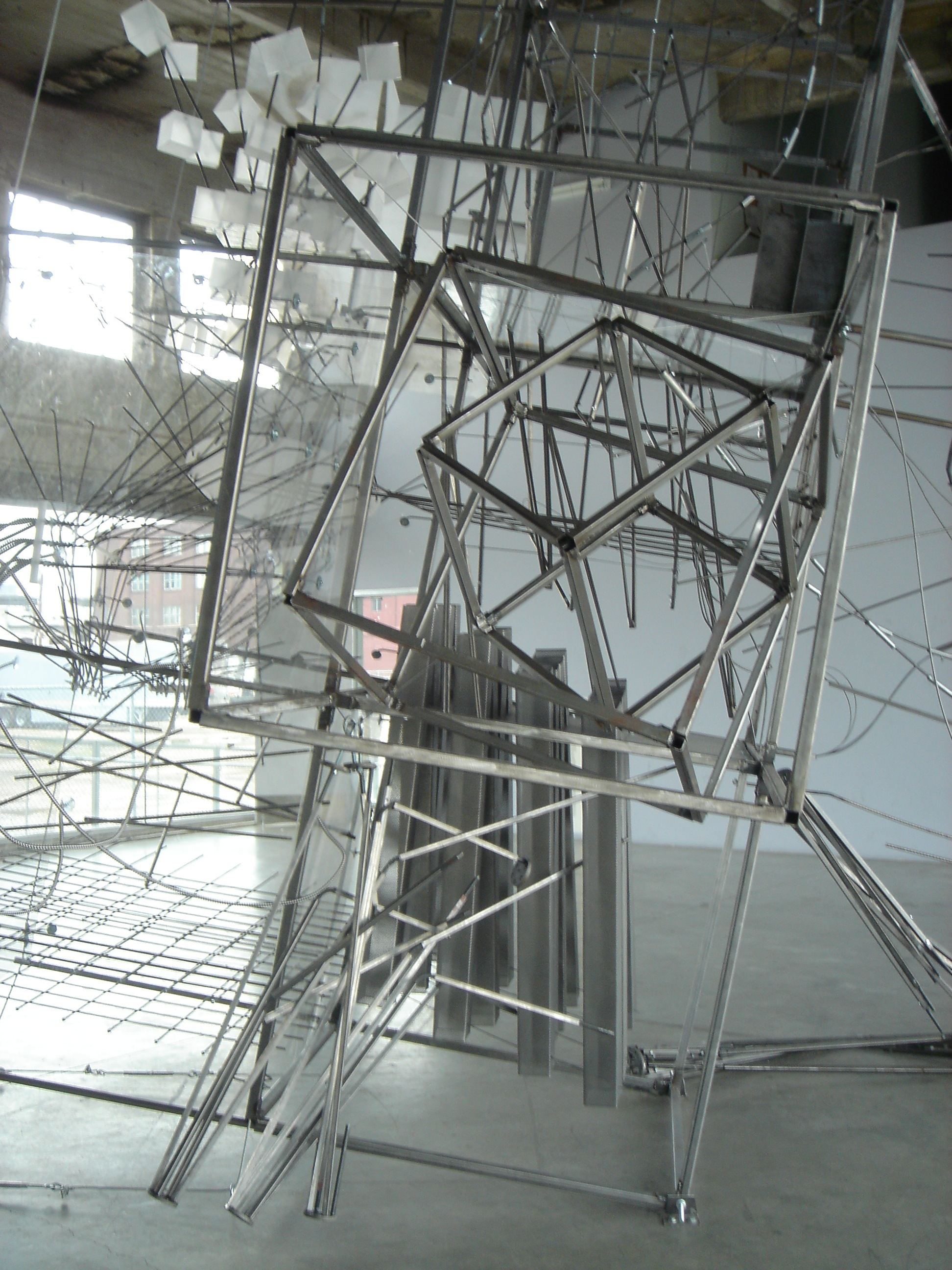

Lebbeus Woods and James Lowder. 2004. Analogical Architecture: Space of Conflict. Vertical Studio at SCI-Arc. Photo courtesy of James Lowder.

When a sensitive and inquisitive intellect invests a great deal of energy in education, there is a rather compelling yet terrifying question that arises, one that puts the most seasoned educator on their heels, rocks their confidence and simultaneously provokes states of anxiety and urgency, a nervousness tinged with the excitement and potential of discovery.

What exactly does one teach when one teaches?

This seemingly simple question is perhaps the most fundamental and profound challenge a teacher can posit, and it is a question that Lebbeus asked himself frequently and with a great sense of urgency, as evidenced in his numerous blog entries entitled Architecture School. (here, here, here, and here)

In the first blog entry of the series, entitled Architecture School 101, Lebbeus states:

A teacher must understand the difference between training and education. The trans-disciplinary nature of architecture, the depth and diversity of knowledge it requires, as well the complexity of integrating this knowledge into a broad understanding that can be called upon at any moment to design a building or project, goes far beyond what anyone can be trained to do. Still, some teachers try to train students, using all the finesse of training dogs. Even those who disclaim rote learning and ‘copy me’ methods can carry vestiges of attitude that amount to the same. A good test is whether the students’ work in a design studio is diverse and individual, or is similar or even looks like the personal work—the ‘design style’—of the teacher. The best teachers preside over the flourishing of individuals and their ideas, and the resulting diversity. Diversity is the essence of education.

In this statement, Lebbeus is not only taking to task the range of dominant pedagogical models found today in architecture schools, but also the underlying ideology upon which most educational institutions are fundamentally predicated – the transfer and advancement of a body of knowledge and with it, the promise of progress. Heavily influenced by the scientific method, (consisting of conducting research,positing a hypothesis, testing the hypothesis, and measuring results in order to verify or discredit the hypothesis), these forms of knowledge tend to privilege what is readily communicable, observable and digestible within a given timeframe, namely issues concerning technique, history and discourse. The incremental moments of novelty that register advancement within a defined discipline only serve to reinforce, if not constrict, the very boundaries of the field they may have wished to push and explore.

Although it could rightly be argued that these concerns are fundamental to the education of an architect, I contend that they also leave much to be desired in the cultivation of one’s own particular sensibility. While they aim at clarifications and along with them, at certainties, they also confuse and stifle the more personal development and expression of the individual student. If a school is to truly take on the difficult problem of educating the next generation of architects, it must educate not only the intellect but also the senses.

Lebbeus Woods and James Lowder. 2004. Analogical Architecture: Space of Conflict. Vertical Studio at SCI-Arc. Photo courtesy of James Lowder.

With the education of the senses, one is reminded of the adage of Josef Albers, perhaps the single most influential teacher of the artistic disciplines in the Twentieth century. He frequently stated that his teaching consisted of nothing more than orchestrating exercises, a mechanism “to open the eyes.” To follow Albers, teaching is not learning about styles or techniques, but rather learning how to see with precision and intent; it was a process of self-discovery through direct observation. It requires an ardent pedagogical stance that cultivates a visual awareness in the student, stripping the world of the common forms of engagement and remaking it into a field of plastic qualities and temporal relationships that expose the beauty in the wide array of objects that constitute our daily existence. In this case, seeing and creating are deeply intertwined, and are the necessary foundation for true artistic expression and experimentation. This pedagogical model clearly had a profound impact on many of the great teachers of last century, particularly at the Cooper Union – Lebbeus was no exception.

That being said, I would argue that Lebbeus’ interests as a teacher went beyond providing a framework where students can learn how to see. His ultimate goal was the cultivation of an attitude towards their education, a sensibility. He used the pedagogical method of Albers as a spring board into an unknown territory of experimentation, discovery, and ultimately, emancipation. Many of today’s institutions more than ever cater to, or serve as an appendage of, the established architectural profession; and the once fruitful scientific method of inquiry in the design studio is slowly transformed into a conceptually inert pedagogical model that reinforces and calcifies the status quo (with moments of originality and excellence notwithstanding). In such a landscape, the would-be experimental architect must find methods and tactics to antagonize, destabilize and usurp the existing confines. Viewing the imposed conventions in the academy as no different as those found in architectural practice of the ‘real world’, Lebbeus embraced “inquiry as an anarchic enterprise”, the concept central to Paul Feyerabend’s canonical text Against Method, as his own method in the design studio.

In pushing beyond simplistic self-expression, Lebbeus exposed experimentation as a truly complex process, a result of an anarchic enterprise as opposed to a rational one, which contradicts familiar and dominant structures of knowledge-building and reframes the very definitions of learning and interpretation. Such a reframing necessitates new forms of observation and interaction, reveals resistances to the normative means of critical judgment, and produces an architecture that is at its core discursively unmanageable. Upon first encounter, the student is confronted with a pedagogy that is indeterminate, contradictory and at odds with familiar forms of knowledge building. Yet, precisely this kind of encounter carries the potential to return architecture to its origins – the experience of the Other – thus forcing the student to make the unknown intelligible, provoking new content. This form of engagement requires a recalibration of faculties, as previous structures of framing disciplinary knowledge are now inadequate. It is, in the end, a process that does not provide answers, but rather points to more questions.

Lebbeus Woods and James Lowder. 2004. Analogical Architecture: Space of Conflict. Vertical Studio at SCI-Arc. Photo courtesy of James Lowder.

Within the studio, Lebbeus was able to do this by transforming his students into collaborators in an experiment. He set up the conditions for a shared experience by vigorously engaging and attacking those aspects of the discipline that are indifferent towards challenges, powerless if asked to face it. Students and teachers alike were aggressively stripped of the existing structures of engagement: all previous forms of thought were rendered impotent. More than a few students quickly started to feel anxious, exposed, and a little more than just uncomfortable, neck deep in an unfamiliar territory. And, while frustration and aggression were not uncommon responses to what could be easily seen as an invitation to the fragmentation of their psyche, the students (either out of exhaustion or out of necessity), would find themselves with no other option than to rebuild themselves from within and without an external discursive framework. What could be said of the student certainly applied to the teacher, and Lebbeus did not take a role any different in terms of risk. What he imposed upon others was taken up by him as well.

I cannot help but be reminded of the Ignorant Schoolmaster, where Jacques Ranciere described the method by which illiterate parents taught their children how to read. The parents, in their ignorance, could not provide any answers, but they could provide for their children a structure built upon questioning. The children would have to engage and be responsible for their own education and, as a result, for their own emancipation.

Lebbeus’ goal for the design studio shared nothing less than this ambition.

— James Lowder is a professor at the Irwin S Chanin School of Architecture at the Cooper Union and a long-time colleague of Lebbeus Woods.