This is the first post in a series commissioned by Aleksandra Wagner for The Drawing Center that will expand on topics related to the exhibition Lebbeus Woods, Architect, which is on view in our Main Gallery until June 15th, 2014. The form is inspired by Lebbeus’ own masterful and insightful blog which can be read here. Here is a list of the upcoming themes and contributors:

1. Paul Miklowitz: THE STATE OF THINGS

2. Vladan Nikolic: THE STATE OF SCIENCE FICTION

3. Chris Mann: THE STATE OF USEFULNESS

4. Todd Kesselman: THE STATE OF BEAUTY

5. James Lowder: THE STATE OF EDUCATING, THE SENSES

6. Aleksandra Wagner: THE STATE OF HOSPITALITY

Brett Littman

Executive Director

Laura Indick

The Bottom Line Editor

Paul Miklowitz

THE STATE OF THINGS

What is a State? A condition, status, something static—thus true, the True, the Platonic Form, stable Being in contrast to changeable becoming. “The state of things” is an eternal verity, the Nature of the Real. And yet…if one needs to ask about the state of things, those things must be in constant flux—changing their state—evolving. Or devolving more likely, sliding from the Ideal to the all-too-human real: unfortunately, the political state has never actually been much like the True and so stands in constant need of change. It is in this contradiction that Lebbeus Woods moved, from it that he took so much of his creative power.

Perhaps no art form is more infallibly governed by laws than is architecture; after all, it must submit to the necessity of physical causality—the State of Nature—or literally fail to stand. Laws of Nature are not optional, not mere matters of taste or style, or even of merely temporary fact; their necessity is absolute, they leave free will no room to move. Yet Lebbeus dared to challenge even this necessity; not knowing how to do something, he tells us, never stopped him from trying to do it. “Aerial Paris” comes to mind.

As for any actual, flawed and fleeting political state, with its nexus of compromises and repressions, its hierarchy of sovereigns and subjects, of wills to power dominating and being dominated—on this ideological battlefield, Lebbeus proposed strategies and interventions that faced down hypocrisy and let chaos back in. Learning from Nietzsche, Lebbeus affirmed contradictions and complexity, and he boldly challenged the bad faith of the political State that would efface its own origin in violence and destruction: his “scabs” and “scars” spit in the face of the State and its lies about itself, calling attention to this sorry state of things in order to undermine the State as thing-in-itself.

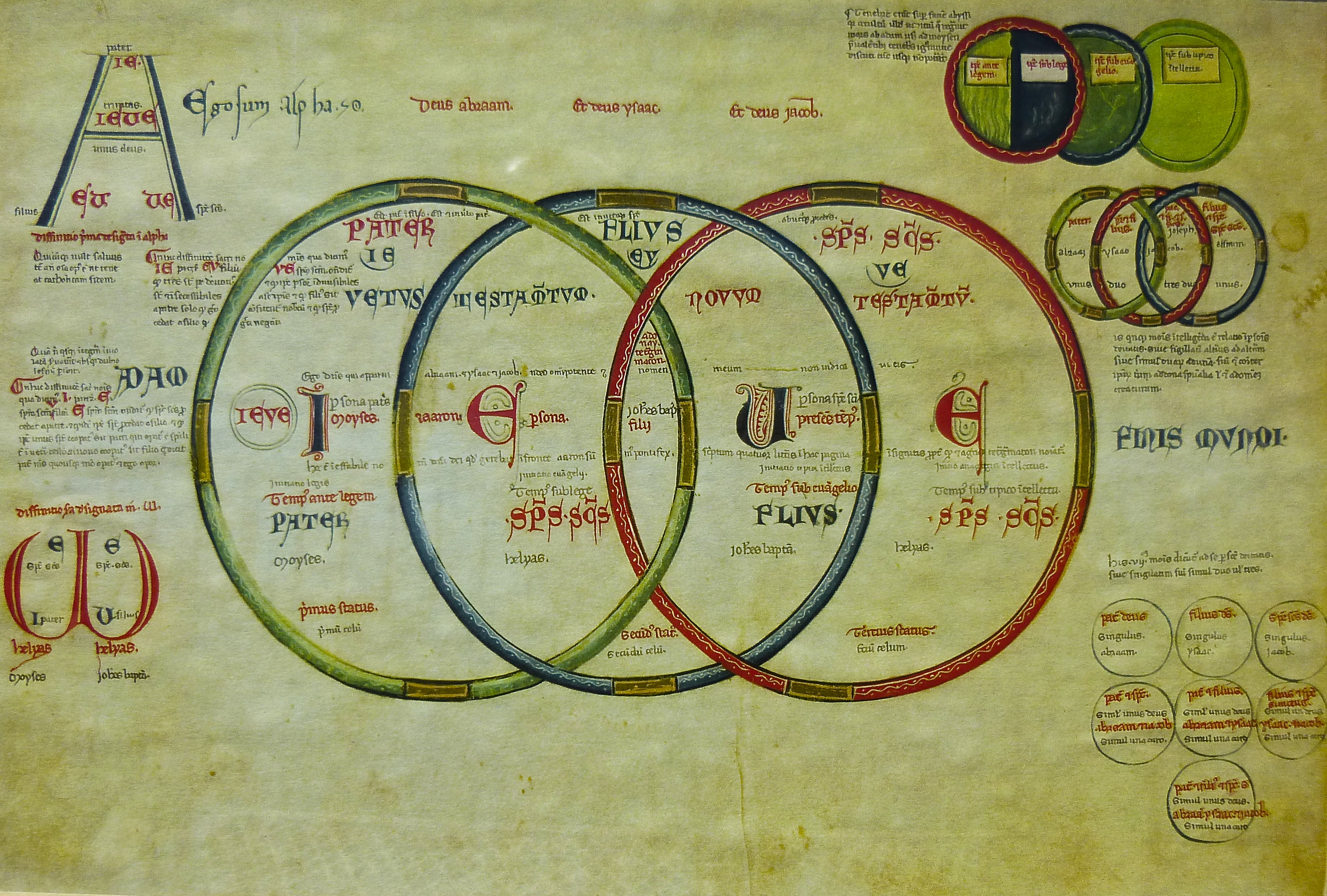

Joachim of Fiore (ca. 1135-1202), Il Libro dell Figure dell’Abate Gioachino da Fiore (Turin, 1953), Vol. II, Tavola XI

And what kind of “thing” did Lebbeus produce? Architects design buildings, and Lebbeus did that. But buildings, as the word suggests, get built—and Lebbeus’ buildings didn’t. One could say that this oversight, the absence of meaning-fulfilling realizations in concrete that buildings must represent for an architect, was the fault of physics: intransigent, oppressive, inflexible laws that bully smaller minds into confining themselves to the merely possible. At the opening of the recent SFMOMA show, a curator remarked that the museum focuses on works of “conceptual architecture,” and hence that the Lebbeus Woods show was a natural for them—but I think this too-easy label is really importantly inaccurate to describe his work. “Concept” implies language—and although there is plenty of language, highly articulate, conceptually sophisticated language, in and associated with many of Lebbeus’ projects, the drawings are not “conceptual,” in this sense at least. Rather, they are vividly, tangibly, viscerally perceptual. And yet, “perceptual architecture” would be a meaningless term, since all architecture is by its very nature perceptual. What Lebbeus does is something far more original, and rare, than either the straightforwardly conceptual or the merely perceptual: something like a new kind of seeing-as-thinking. It reminds me of the attempt to visually represent the three dispensations of historic time in Joachim of Fiore’s thirteenth century mystical/heretical Liber Figurarum (above): a new kind of writing that isn’t writing and yet is, a new kind of picturing that is simultaneously something else, something concretely abstract, or abstractly concrete. Something impossible—yet brazenly actual. Such a new kind of thing that it isn’t clear what kind of thing it is.

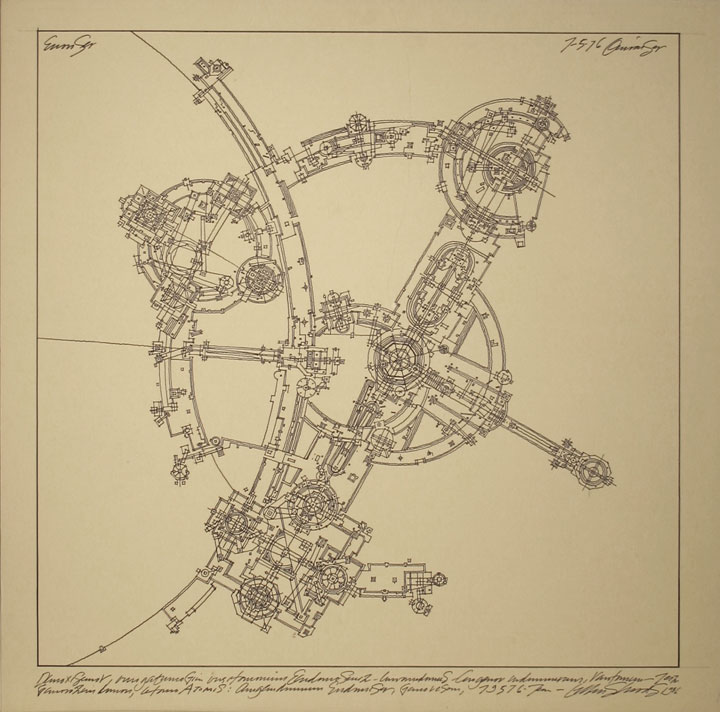

I’m thinking (primarily) of those works that achieve a unique hybridity: “artist’s renderings” of complicated, dubiously possible buildings, accompanied by the architect’s floorplans. One of these pairs (above) in particular is breathtaking. A large square composition, it depicts a kind of castle complex, with towers and bridges and battlements surrounded by forest, superficially resembling certain of M.C. Escher’s graphic visions, but far more visually complicated than Escher and much less simply paradoxical. At first, the building looks “realistic” because it is so astonishingly well-rendered (and all done freehand!). But on closer inspection, it is really more like something out of a dream; impossible to completely comprehend despite its very concrete realization, and thus ominous, overwhelming. The accompanying floorplan drawing makes the realization of the unreal even more disorienting: Lebbeus not only imagined the exterior appearance of an improbable structure in vivid and compelling detail, he also imagined its interior anatomy so fully and carefully that it seems it must be actual after all…if only in some future state of things, where the laws of physics have bent still further to the human will. Not the scientist’s this time, but the artist’s.

— Dr. Paul S. Miklowitz, Professor of Philosophy, Cal Poly State University