Vladan Nikolic

THE STATE OF SCIENCE FICTION

Lebbeus Woods has created works, and within his works entire worlds, which in appraisals and reviews often evoke the genre and imagery of science fiction. Yet his concept of science fiction reaches far beyond what the term generally implies. We need labels to classify things, to easily associate and to contrast them to the realms of what we know. By doing so, we inevitably simplify and diminish them, too; some things just defy easy classification.

Science fiction suggests a futuristic scientific universe, but it is also a Weltanschauung, a conceptual world-view that envelops the possible that can be imagined, and the impossible that could come into being, separately, and all at once. It can also comment on our present reality, transcending it into a futuristic-looking hyper-reality – something so real that it surpasses the banality of everyday mechanics and trite politics.

Lebbeus said in a New York Times interview: “I’m not interested in living in a fantasy world. All my work is still meant to evoke real architectural spaces … what interests me is what the world would be like if we were free of conventional limits. Maybe I can show what could happen if we lived by a different set of rules.”

Of course, science fiction can be, and often is, pure fantasy and escapism. The best of it lets us explore our current experiences and our possible futures through bold aesthetic forms and means; it allows us to see things from new angles, and make audacious connections between well-known images and previously unimagined perspectives. In short, it lets us understand our reality in a new way.

Lebbeus Woods. The New City. 1992.

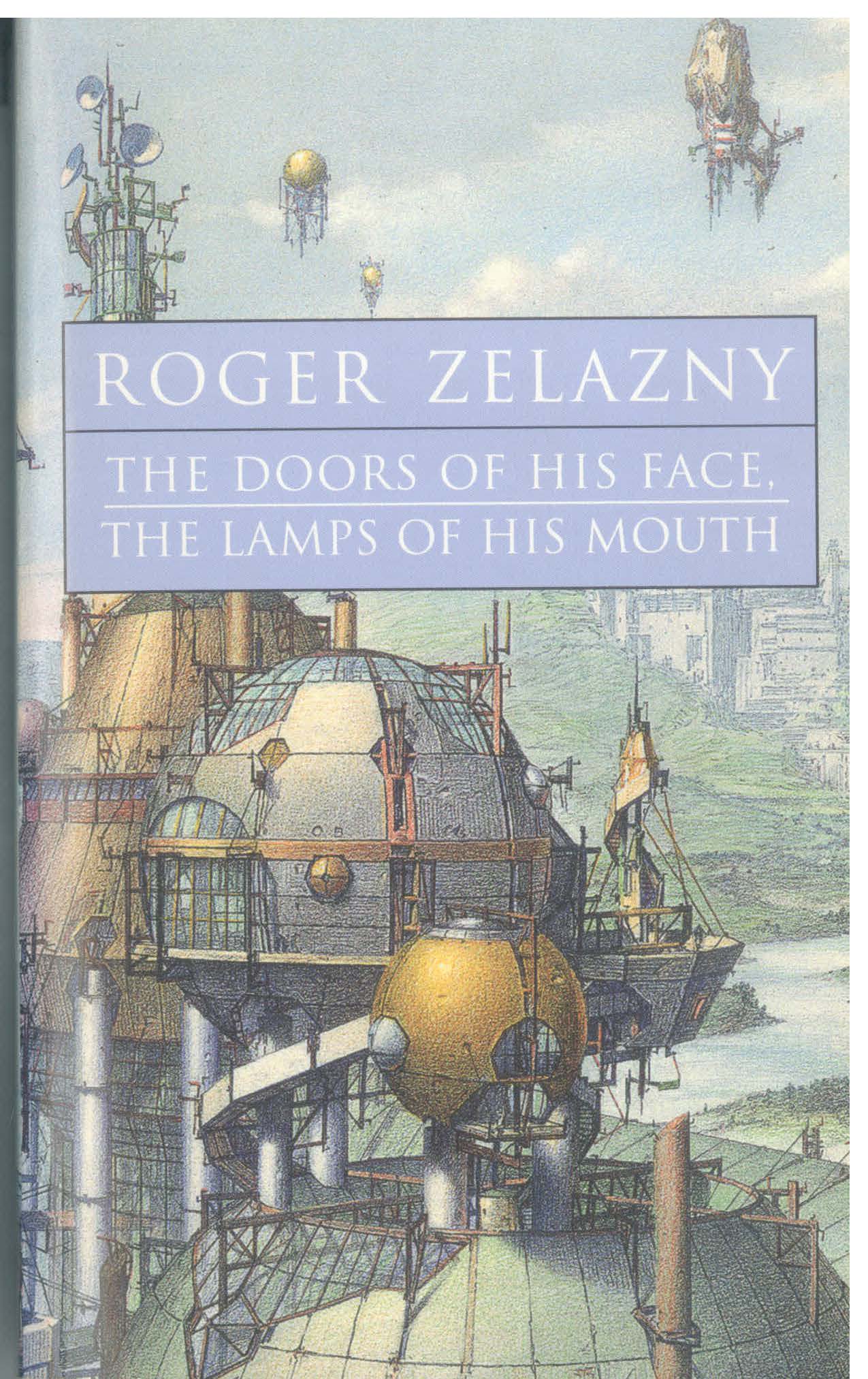

Cover page for Roger Zelazny. The Door of His Face, The Lamps of His Mouth. New York: ibooks, 2001.

(c) Estate of Lebbeus Woods

As filmmaker and storyteller, this is also where my interest in science fiction lies. Our surroundings are rapidly changing, and so are we. Consumer society, all-pervasive media, terrorism and state surveillance, a general sense of paranoia and disconnectedness, sanitized violence, and helplessness of the individual are already realities that shape us. Through fragmented but connected narratives, science fiction can explore how these external realities affect the internal world of the individual and, in turn, can redesign the external realm: issues of control, individual choice, and personal responsibility are intertwined with the way we are conditioned by society, our environment, and how we construct our concept of reality.

Another architect who had become a well-known filmmaker once told me that all architects want to be filmmakers. To me, Lebbeus was both. As a filmmaker, I would have probably focused mostly on the story of Alien3 and tried to find the best visual way to tell it; as initial conceptual architect and designer for the film, Lebbeus created the world, which told the story. In the end, his designs were not used.

The monster in science fiction film has been continually re-made, as have new worlds and altered states. Initially supposed to reflect our collective fears of the unknown, each new re-make has added better special effects without adding much new meaning, making the “profound” redundant at best, banal and simplistic at worst. Nowadays, conventionalized meanings and escapist fantasy have come to dominate what was once the most daring genre. Occasionally, a veneer of supposedly subversive subtext is added to the mainstream blockbuster, but this mostly feels like calling the same old used car a new “pre-owned vehicle.”

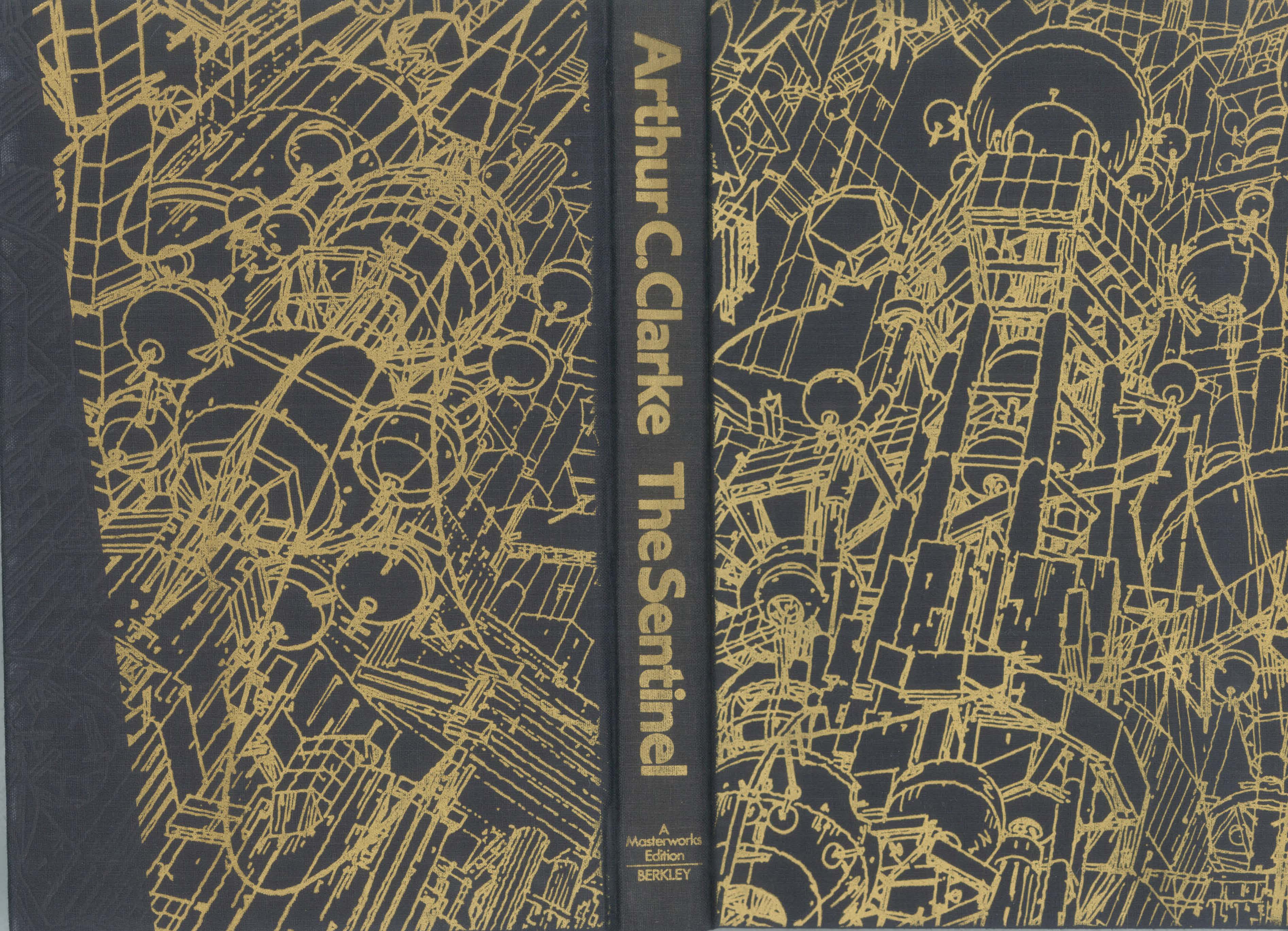

Lebbeus Woods. 1983.

Cover for the limited hardcover edition of Arthur C. Clarke. The Sentinel. Masterworks of Science Fiction and Fantasy. New York: Berkley Books, 1983.

(c) Estate of Lebbeus Woods

One of Lebbeus’ favorite films was Chris Marker’s 1962 film La Jetée, another work that is termed “science fiction,” but which completely transcends the genre. It does not even contain moving images — told through a series of photographs, connected through a narrator, the film is a study of the impact of images, memory, and time. But as Lebbeus points out in his blog, the story is actually quite conventional; he asks the question of how Marker managed to turn routine ingredients into a masterpiece. For Lebbeus, the film’s power lies “in a simple phrase: the power of evocation. For everything that is not shown, the filmmaker counts on the power of imagination of his viewers….”

To me, this is the magical sentence that encapsulates the power and potential of science fiction to evoke something beyond the fear of the future. I don’t believe in summaries and explanations, but perhaps, to those still having the time to listen and think, the conclusion to that same blog entry on La Jetée illuminates what science fiction can be:

“The La Jetée approach in architecture must be as abstract as architecture itself. So, the creation of spaces of the imagination can only be found, it would seem, in an architecture of fragments, loosely joined like neurons in the brain, separated by synapses that can only be bridged by an electrical charge of thought. The key to such an architecture would be the potency of its fragments and thus its capability to inspire leaps of imagination that join them into a whole within the mind. Exactly how such an architecture would appear to us we cannot know at present, as its emergence is still in the future.”

Vladan Nikolic is associate professor of Media Studies and Film at The New School and an award-winning filmmaker. His science fiction feature film ZENITH (2010), which is also part of an extensive transmedia project, has been released in a unique and innovative way, combining theatrical, video, and online releases over multiple platforms, resulting in millions of downloads and a cult following.