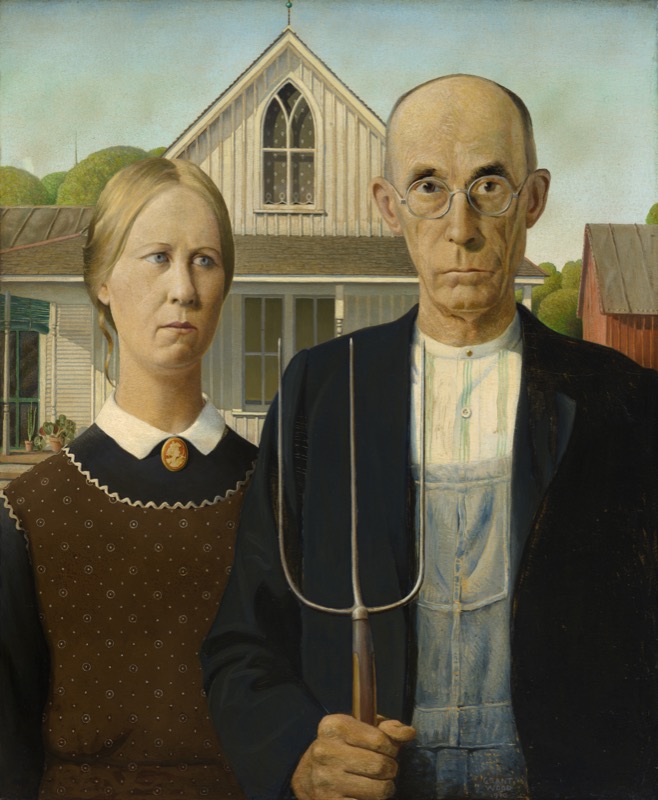

On view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables is the museum’s first retrospective of the Regionalist artist Grant Wood in more than thirty years. He is most famously known for his painting American Gothic (1930), an iconic portrait of two American Midwestern farmers, a male and a female, standing in front of a white Carpenter-Gothic style house.

Grant Wood, American Gothic, 1930. Oil on composition board, 30 3⁄4 x 25 3⁄4 in. (78 x 65.3 cm). Art Institute of Chicago; Friends of American Art Collection 1930.934. © Figge Art Museum, successors to the Estate of Nan Wood Graham/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph courtesy Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, NY.

The exhibition, which occupies roughly half of the museum’s fifth floor, consists of various media that collectively speak to Wood’s range as an artist: drawings, paintings, prints, murals, decorative objects, and so on. His early roots in decorative art are evident at the very beginning of the show, where a set of quirky, even surreal corncob chandeliers designed for the dining room of a Cedar Rapids hotel greets visitors among other decorative objects.

Wood, who was born in 1891 on a farm near Anamosa, Iowa, began his artistic practice as early as high school. His seminal influences include Ernest Batchelder and Arthur Wesley Dow of the American Arts and Crafts movement, whose lessons he studied in the pages of the journal Craftsman and Composition. While he gained early critical acclaim from his decorative objects, his lack of commercial success forced him to rethink his practice and instead focus on fine art; his trips to Europe between 1920 and 1928, in particular, inspired him to paint. Like many of his artist peers, he went to study the French Impressionists and for a period of time painted after them (these works are among the first paintings presented in the exhibition). It was a visit to Antwerp, however, where he saw paintings by Hans Memling and other Flemish Old Masters, that would have a lasting impact on him and inform his approach to painting for years to come—this is especially noticeable in his portraits.

Even after shifting from decorative to fine art, Wood still firmly believed in the aesthetic as well as democratic values underlying the former. According to Whitney curator Barbara Haskell, “his ideology and pictorial vocabulary remained grounded in Arts and Crafts,” specifically “his later use of flat, decorative patterns and sinuous, intertwined organic forms as well as his belief that art was a democratic enterprise that must be accessible to the average person, not just the elite.” As Wood himself maintained, “a work which does not make contact with the public is lost.”

This shift coincided with Wood’s renewed interest in local subject matter, specifically that of Iowa and the Midwest; feeling defeated when a solo exhibition at Paris’ Galerie Carmine failed to attracted press as well as sales, he returned to Iowa to experience familiar surroundings anew: “[I returned] from my third trip to France to see, like a revelation, my neighbors in Cedar Rapids, their clothes their homes, the patterns on their tablecloths and curtains, the tools they use. I suddenly saw all this commonplace stuff as material for art. Wonderful material!” His interest in portraying Midwestern farmers as subjects eventually inspired him to paint American Gothic, which quickly garnered national attention. While it was interpreted by some as a satirical portrait of the couple and of farming life in the Midwest, Wood insisted that he had nothing but genuine admiration for the two subjects.

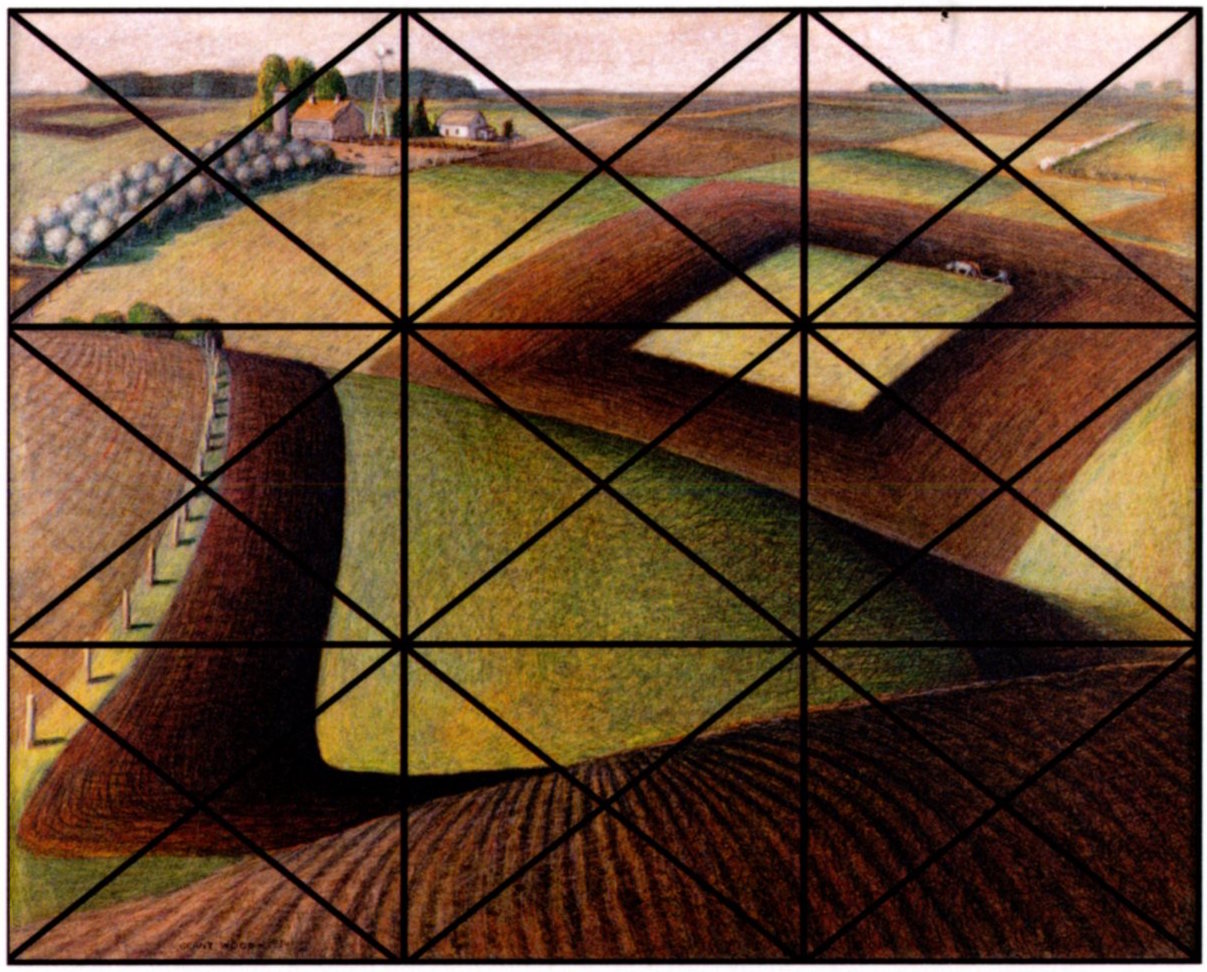

Grant Wood, Fertility, 1939. Charcoal on board, 18 x 24 in. (45.7 x 61 cm). Promised gift to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas. © Figge Art Museum, successors to the Estate of Nan Wood Graham/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph by Dwight Primiano.

As the Whitney exhibition points out, drawing was integral to Wood’s process. For every painting or lithograph, he drew a full-scale study beforehand. He developed his landscapes by using the principle of thirds, a compositional device which involves overlaying a grid of nine squares on top of a drawing and making adjustments so that the key visual elements of the landscape are positioned at the intersections of the grid. His use of this device speaks to his focus on composition before narration, an approach derived from his Arts and Crafts roots as well as from Flemish Old Masters. As such, he viewed his work as an abstraction before representation: “I make a design of abstract shapes without any naturalistic details. Until I am satisfied with this abstract picture I don’t go ahead. When I think it’s a sound design, then I start very cautiously making it look like nature.”

Despite his swift rise to fame and his quintessentially regionalist beliefs, Wood was perhaps as much an outsider as he was a warmly accepted member of the community to which he claimed to belong. As Haskell notes, Wood did not conform to the masculine ideals of the Midwestern farmer that he perpetuated in his images. The press frequently alluded to his queer identity through various euphemisms such as “cherubic” and “soft-spoken,” as well as by pointing out his status as a “shy bachelor.” At times, his queerness was suggested (never directly stated) as a means of discrediting him. In an attempt to oust the artist from his teaching position at the University of Iowa’s studio program, department chair Lester Longman often made veiled references to Wood’s sexuality.

Wood arguably manifests his same-sex attraction through his depictions of male subjects, who are oftentimes shirtless and laboring in the fields. As Peter Schjeldahl of The New Yorker observes, “no special sleuthing is needed to winkle out his desires from his enraptured depictions of hunky men versus his stony ones of women, and the recurrent suggestion of male anatomy in his bizarre Iowa landscapes.” The Times’ Roberta Smith also notes that the artist’s male subjects are “noticeably more engaging than those of women.” The painting of his studio assistant and former student Arnold Pyle, entitled Arnold Comes of Age (1930), is an especially intimate portrait that quietly speaks volumes to Wood’s desire toward him. A commemoration of Pyle’s twenty-first birthday, the portrait depicts a slender youth whose elongated features recall the Mannerist portraits of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Inspired by the Flemish Old Masters’ use of symbolism, Wood depicts the sitter’s transition into adulthood in more ways than one. For instance, a butterfly, a universal symbol of metamorphosis, flutters by the sitter’s right elbow. As art historian Richard Meyer argues, the butterfly also represents Pyle and Wood’s frequent visits to the Butterfly Teashop, a Cedar Rapids café, moreover opening up “both the social relationship of artist to sitter and the possibility of a private or encoded visual message from the former to the latter.”

Grant Wood, Arnold Comes of Age (Portrait of Arnold Pyle), 1930. Oil on composition board, 26 3⁄4 x 23 in. (67.9 x 58.4 cm). Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln, Nebraska; Nebraska Art Association Collection 1931.N–38. © Figge Art Museum, successors to the Estate of Nan Wood Graham/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph © Sheldon Museum of Art.

Meyer’s notion of an encoded message speaks to a larger point: that homosexuality, until recently, has “rarely operated at the level of conscious articulation within the history of art.” Thus, he argues: “Dealing with this fact means attending to homosexual identity not only as a fully formed and visible category of difference but also a structuring absence, or blank spot, within the historical record.” While Arnold Comes of Age lacks overt homosexual desire, it is this very absence coupled with his use of symbolism that is telling of how queerness as an identity lacked social recognition during Wood’s lifetime; on a more intimate level, the lack of overt details or references arguably reflects his own personal struggles with his sexuality.

As a queer artist whose subject matter seems at first to solely suggest national fervor, Wood presents himself at the Whitney as a man full of contradictions, but ultimately a revelatory surprise for me.

Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables is organized by Barbara Haskell, Curator, with Sarah Humphreville, Senior Curatorial Assistant. The exhibition is on view through Sunday, June 10, 2018.

—Austin Yoon, Curatorial Intern, The Drawing Center