This is the fourth post in a series commissioned for The Drawing Center that will expand on topics related to the exhibition Lebbeus Woods, Architect, which is on view in our Main Gallery until this Sunday, June 15th, 2014. The form is inspired by Lebbeus’ own masterful and insightful blog which can be read here. The first three posts are available: here, here, and here.

Todd Kesselman

THE STATE OF BEAUTY

What is palpable in the current exhibition Lebbeus Woods, Architect is that the works are masterful, breathtaking. Many are ‘genius’—to use an outdated aesthetic term—in the sense that they appear (to mere, architecturally-uninitiated mortals such as myself) as if they have emerged out of nowhere, out of the future itself.

But are they beautiful?

One of the definitive achievements of German idealism, and the Romantic movement that followed from it, was to have transformed our understanding of beauty from a question of metaphysical, timeless truths to one of freedom, imagination, and human history. Immanuel Kant, for example, conceived of beauty as that unique experience of pleasure that arises when we find meaningful unified form in the world, without the use of our abstract, conceptual powers of thinking. Beauty, so understood, is our discovery of the paradoxical phenomenon of what Kant called purposiveness without purpose, or lawfulness without law—where form seems to possess lawful order, while at the same time being free from all of the ordinary kinds of laws that we are subject to in everyday life: from social and legal norms, to moral obligations, to the laws of physics.

Since the birth of modern aesthetics, this unique kind of aesthetic order has therefore stood for the creative power of human beings and the freedom of our imagination, in the face of the rigid, non-negotiable natural laws of nature that we’ve come to discover. Our discovery of these laws, and their exactitude, undeniably gave rise to a desire to understand ourselves as something more than the mere marionettes of nature.

If anything general can be said of aesthetic categories in the present, however, it is surely that there is a strong resistance or distaste for unity, integration, and beauty, or anything that appears to offer a well-packaged reconciliation between nature and freedom. Nature and humanity are more at odds than they have ever been, as is obvious to those of us who have spent any time in a lower-Manhattan severely impacted by global climate change. Nature’s revenge is persistently on the horizon. To speak about beauty now, outside of its state of disrepair, and as a serious aesthetic category that persists—as Woods himself did—we must cautiously acknowledge that it can no longer represent for us what it once did for our predecessors. To speak about Woods’ work in the context of beauty firstly requires an acknowledgment that we no longer live the naive optimism of the Romantic age.

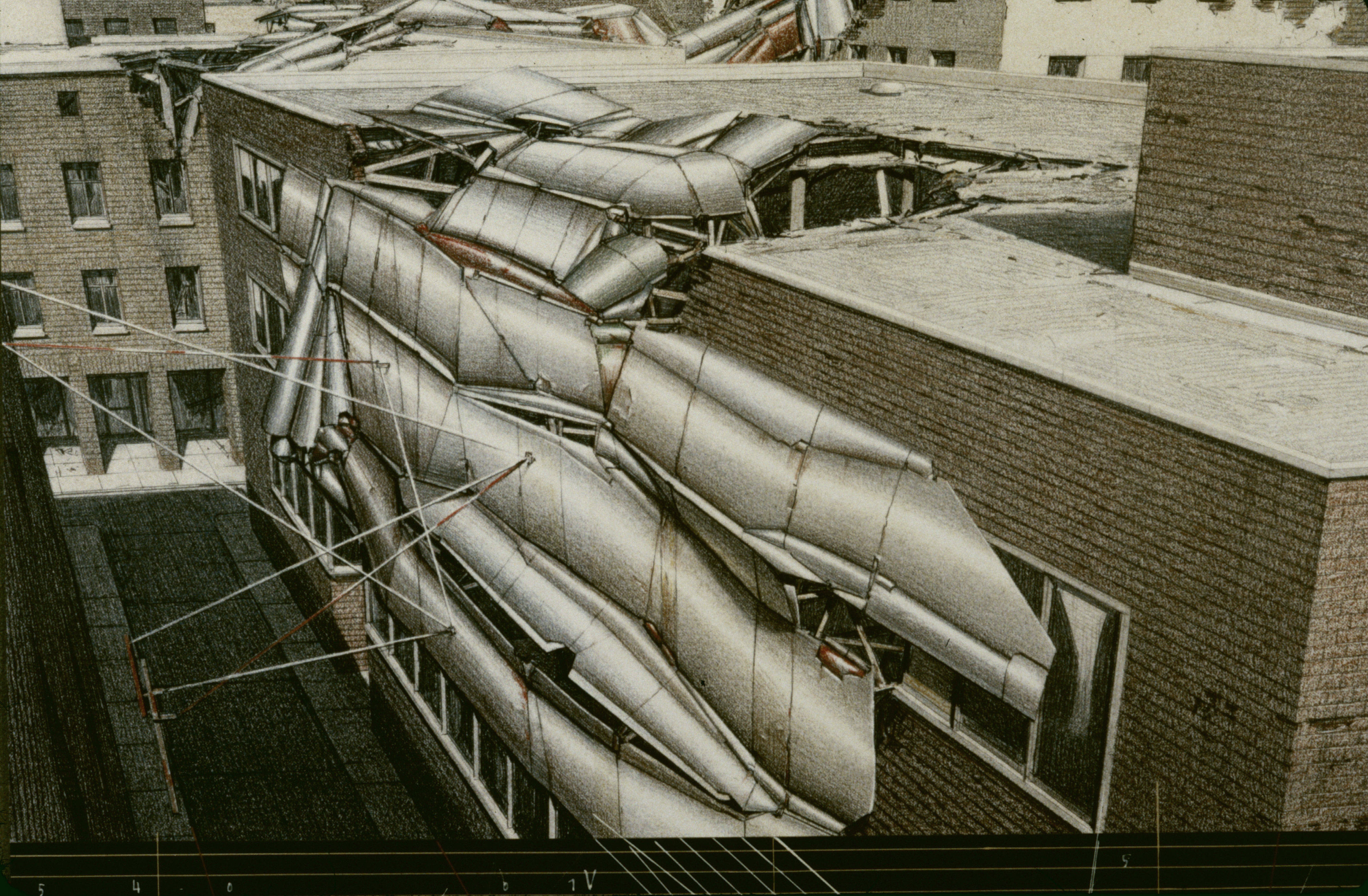

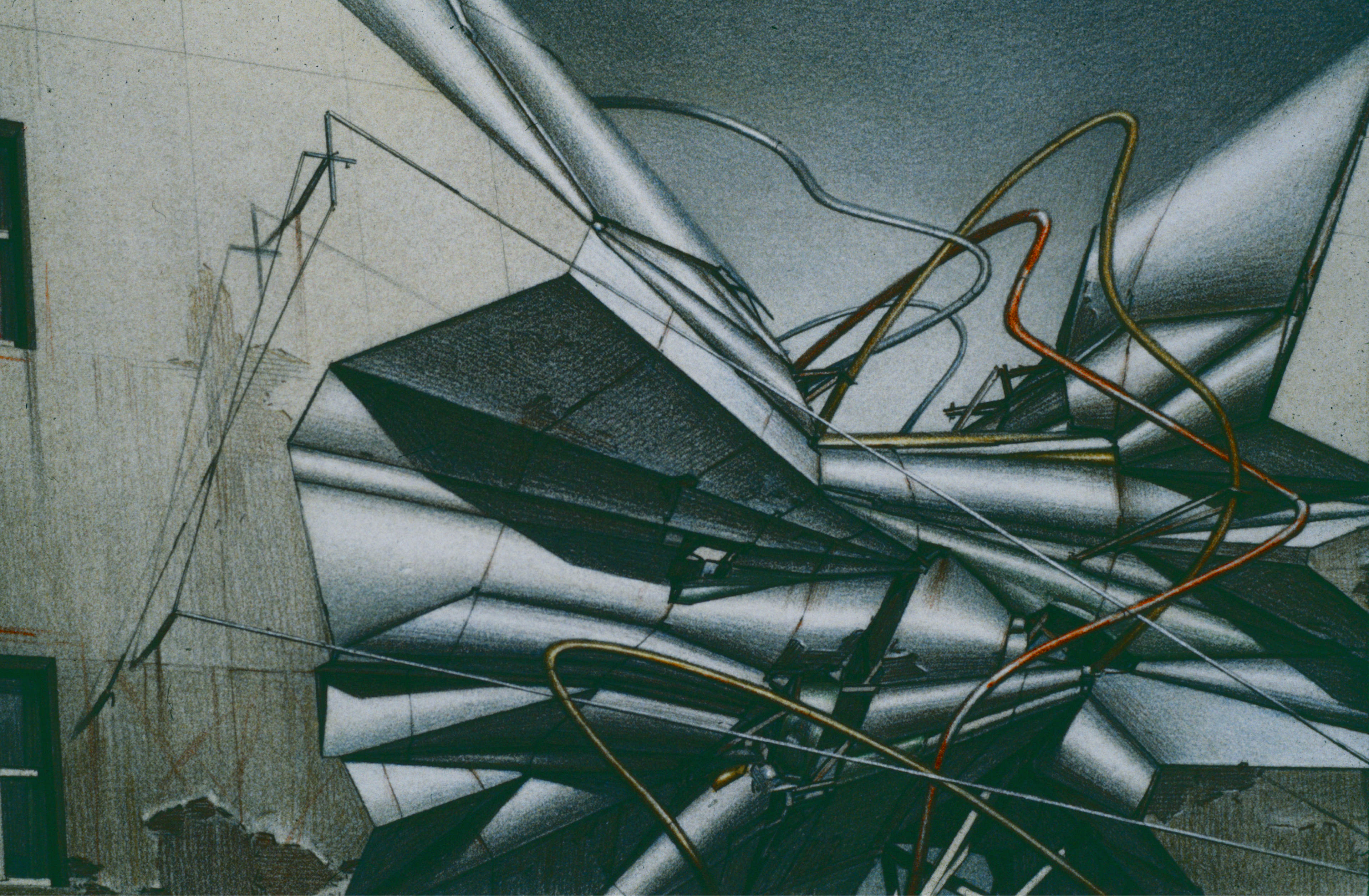

The project from 1993, War and Architecture, directly confronts us with such questions, since it was attacked by critics as an aestheticization of violence: violence made beautiful. Radical reconstruction, such critics would have it, idealizes and cleanses the real loss suffered by the inhabitants of Sarajevo, by transforming it into an object of our aesthetic satisfaction.

The most telling way to dispel such criticism is through a contrast with Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto, which Walter Benjamin quotes at the end of The Work of Art in the Age of its Mechanical Reproducibility. There Benjamin points to the fascist aspirations of the Italian Futurism:

For twenty-seven years we Futurists have rebelled against the branding of war as anti-aesthetic. Accordingly we state: War is beautiful because it establishes man’s dominion over the subjugated machinery by means of gas masks, terrifying megaphones, flame throwers, and small tanks. War is beautiful because it initiates the dreamt-of metalization of the human body. War is beautiful because it enriches a flowering meadow with the fiery orchids of machine guns. War is beautiful because it combines the gunfire, the cannonades, the cease-fire, the scents, and the stench of putrefaction into a symphony. War is beautiful because it creates new architecture, like that of the big tanks, the geometrical formation flights, the smoke spirals from burning villages, and many others. Poets and artists of Futurism! Remember these principles of an aesthetics of war so that your struggle for a new literature and a new graphic art may be illumined by them!

The stakes of War and Architecture rest on its being the uncompromising refusal of this vision of beauty. If you’re looking for fascist aesthetics, Marinetti is your man. Radical reconstruction, on the other hand, is a demand for conditions of human dignity and civic life to be reestablished. Woods’ claim that “architecture is war, war is architecture”—is an injunction for us to consider the past without repressing or erasing the violence and trauma that have been suffered. Works such as Scab (1993) and Scar (1993) are expressions of this idea; they do not take pleasure in the destruction enabled by technology and our capacity to dominate nature. Instead, they are models for the conscious reshaping of the fragments and remnants of war for the purpose of creating new livable ways of life, or the transubstantiation of the materiality of an unlivable past into forms that open up a livable future. In Woods’ own words “the principle of this reconstruction was that found materials would be reshaped, piece by piece, without thereby becoming ‘junk sculpture,’ or a collage of detritus” (The Sarajevo Window). Such forms give rebirth to matter, without denying the violence that has come to pass, without simply returning to the past, and without idealizing a future detached from the reality of history.

If the Futurists transformed beauty from a sign of creativity into a symbol of destruction, Woods’ work overcomes this difference by bringing together, at once, fragmentation and unity. The strange, almost alien result embodied in his drawings make us wonder, What is their purpose? What are they? Why are they what they are? Their purposiveness without purpose, their beauty, is to be found in the fact that we do not know what the future holds, or how to live amongst the wreckage of history. But we can begin by setting the imagination to work in the service of social mourning.

–Todd Kesselman, PhD Candidate, Department of Philosophy, The New School for Social Research