Louise Lawler began her career as part of the Pictures Generation, a loosely-defined group of artists who came of age in the 1970s. Like other members of this group, Lawler is known for using photographs to comment on the way mass media impacts our perception of the world. Now the subject of an intimate retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art, entitled Why Pictures Now, Lawler asks visitors: in what way is the Pictures Generation still relevant today? The exhibition consists of several parts, including a sound installation in the museum courtyard and a series of responses to Lawler’s work by contemporary artists who have carried the tradition of institutional critique into contemporary practice. But, it is the exhibition’s presentation of Lawler’s large scale series of vinyl line drawings, which she calls ‘tracings,’ that best demonstrate how the artist’s later practice has broadened beyond photography, and it is through these works that the artist explores how digital manipulation transforms the way artworks (or pictures more generally) are perceived.

Louise Lawler. Why Pictures Now. 1981. Gelatin silver print, 3 x 6” (7.6 x 15.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired with support from Nathalie and Jean-Daniel Cohen in honor of Roxana Marcoci. © 2017 Louise Lawler.

Lawler’s earlier photographs, taken during the 1980s and 90s, also on view, are the basis for her later line drawings. These photographs provide candid and intentionally unflattering views of art world treasures. Each image captures a work by the likes of Jasper Johns, Jackson Pollock, or Edgar Degas as they are displayed in museums, galleries, and warehouses, or in the well-decorated homes of private collectors. For instance, Lawler’s Monogram shows Johns’s painting White Flag as it hangs in a collector’s home above a bed with a complementing, monogrammed duvet. Works like Monogram expose the contexts that give significance to artworks—their provenance, their price at auction—and speak to the way artworks function in society as symbols of good taste, regardless the artist’s intentions. As such, through these early photographs, Lawler challenges longstanding misconceptions that regard artists, not the frameworks they work within, as purveyors of meaning.

Installation view of Louise Lawler: WHY PICTURES NOW. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, April 30-July 30, 2017. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck.

Imagining possibilities for photography beyond framed works, throughout her career Lawler has printed and reprinted her works across cocktail napkins, postcards, posters, and business cards. In the Adjust to Fit series begun in the late 1990s, Lawler extended this idea by expanding and printing her photographs at a monumental size: to a scale that undercuts the legibility of the image, but fills a substantial predetermined area of wall space. With titles amended by notes like “distorted three times,” works from this group poke fun at the market push to create bigger and by extension ‘more impressive’ artworks with the hope of engendering higher sales.

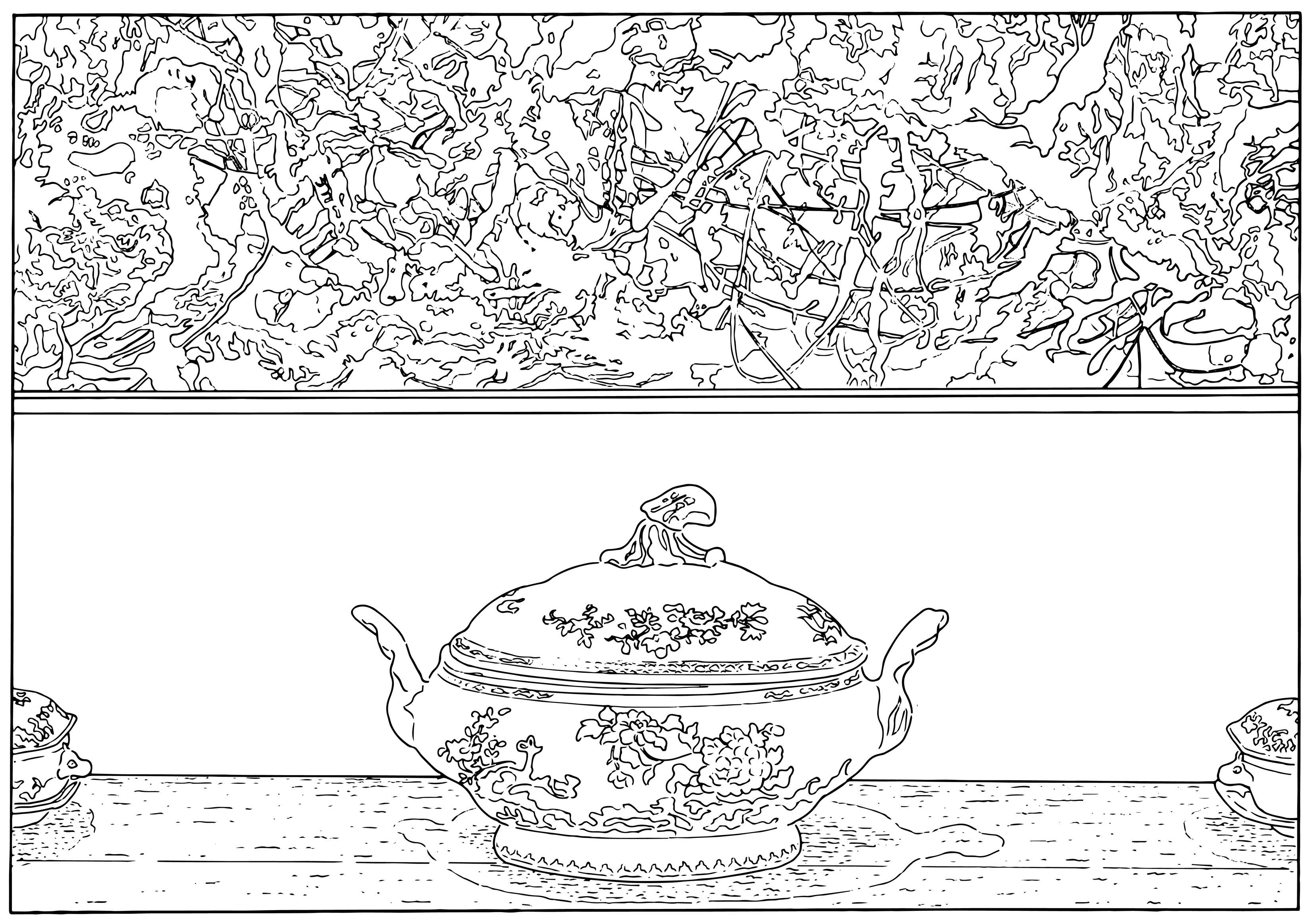

Louise Lawler. Pollock and Tureen (traced). 1984/2013. Dimensions variable. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Endowment for Prints © 2017 Louise Lawler.

Following the logic of her Adjust to Fit series, Lawler’s more recent series, which she calls ‘tracings’, likewise alters her early photographs so that they can be easily enlarged. Collaborating with the children’s book illustrator Jon Buller, Lawler traced the outlines of objects from several of her early photographs, like Pollock and Tureen (Arranged by Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine, Connecticut), 1984, and converted the tracings to vector images that could be blown up to any scale. As in the current retrospective at MoMA, the ‘tracings’ are then printed on vinyl at a larger-than-life size and affixed directly to the wall. Using drawing, the ‘tracings’ mark the artist’s understanding of how the meanings of contemporary artworks change not only through institutional context but also through manipulation of the archives that act as artwork documentation. For Lawler, who has long guided viewers to examine the lives of artworks after leaving the artists’ studio, the ‘tracings’ stand as the most recent admission of the ever-more-numerous ways the artists’ hand is removed from the work.

Louise Lawler: Why Pictures Now will be on view at The Museum of Modern Art in New York through July 30. The exhibition is organized by Roxana Marcoci, Senior Curator, with Kelly Sidley, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography.

—Amber Harper, Assistant Curator, The Drawing Center

Installation view of Louise Lawler: WHY PICTURES NOW. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, April 30-July 30, 2017. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck.