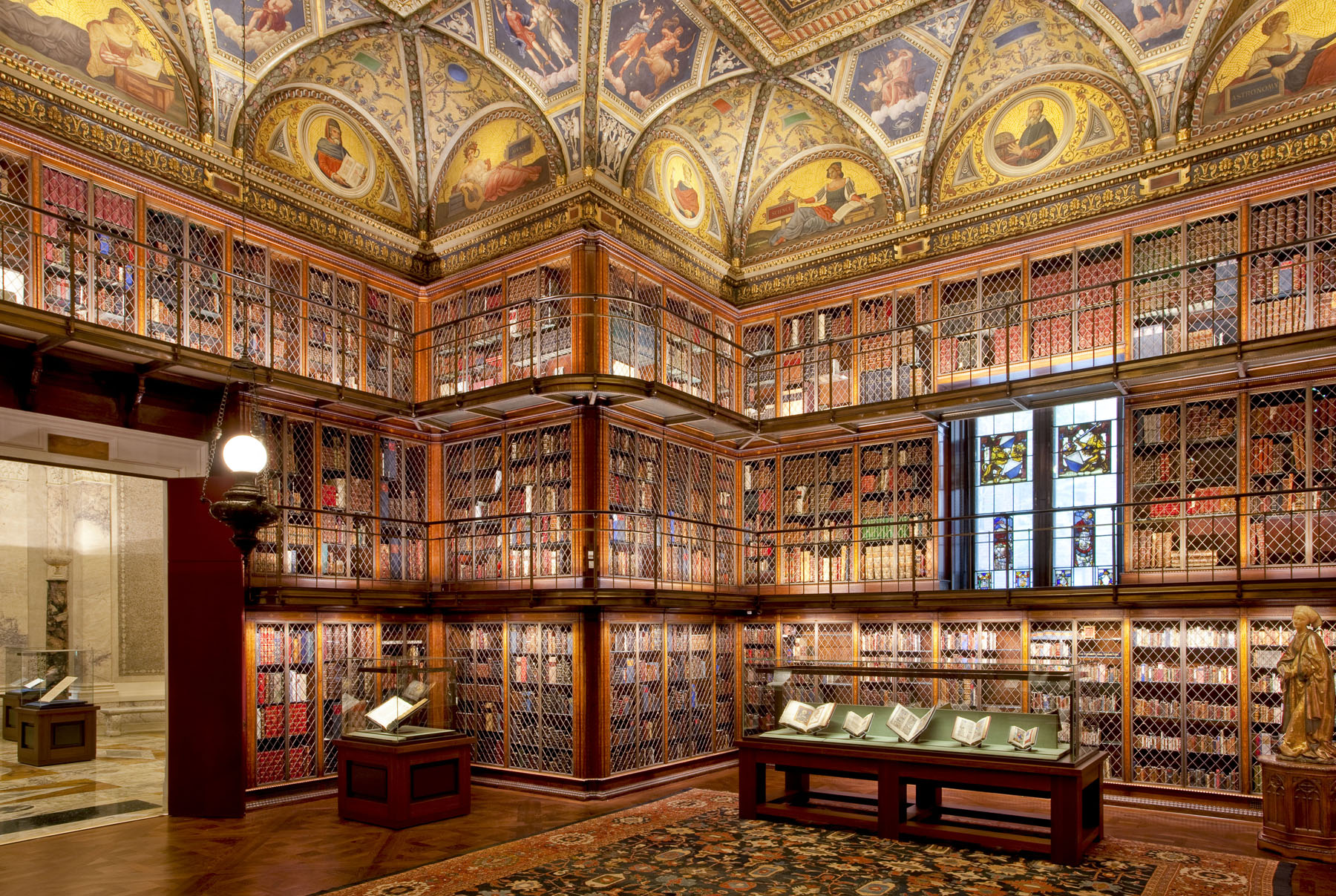

Pierpont Morgan’s Library. The Morgan Library & Museum. Photography by Graham Haber. Image courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum.

On a recent visit to the Morgan Library and Museum to see the Delirium: The Art of the Symbolist Book exhibition I started thinking about the relationship between museums and their affiliated libraries. The Morgan, for instance, presents its library mission front and center, creating relationships between books for research and display purposes that engage the public on two fronts. Reflecting on other museum affiliated libraries of similar size and style, it became clear to me that the initial distinctions between library and museum start to fade. Libraries are thought to be quiet, solitary, and aimed at answering specific questions, while museums are social and encourage curiosity and discussion, yet in the right hands, they can unite to enhance one another, and most effectively engage and educate the public. Museums like the Morgan, Frick Collection, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art have found ways to integrate holdings from their research libraries into the outward thinking, public missions of their exhibition programs.

The Reading Room at the Morgan Library & Museum. Photography by Michel Denancé. Image courtesy of The Morgan Library & Museum.

Retaining ‘library’ as part of its institutional moniker, the Morgan preserves the closest relationship between its collection of artworks and extensive book and manuscript holdings. Functioning like a ‘library for drawings,’ the Morgan’s Drawing Study Center is described by museum staff as a ‘think tank’ for curators and fellows, many of whom are doctoral candidates or early-career scholars. Fellows at the center, which has been critical to the museum’s mission since 1999, often complete projects informed by artist engagement with texts and language, including research on medieval illuminated manuscripts, late-sixteenth century drawings of Homer’s Odyssey, and the relationship between drawing and writing in works by American artist Cy Twombly and French artist Jean DuBuffet. The Morgan’s exhibition program takes on a similar theme, alternating between shows that highlight texts from the library catalogue and artworks from the museum collection. By integrating texts and literary subjects into even their exhibitions of visual art, the Morgan reminds interested parties that they can also spend time in libraries and reading rooms to further satisfy their curiosity.

Public Entrance of the Frick Art Refrence Library. Photo by Michael Bodycomb. Image courtesy of The Frick Collection.

The Frick Art Reference Library of the Frick Collection (on New York’s Upper East Side) was founded by Helen Clay Frick, the daughter of the Gilded Age industrialist and art collector Henry Clay Frick. The Frick Art Reference Library’s collection includes books, auction catalogues, photographs, and electronic resources, which focus on painting, drawing, sculpture, and printmaking, with additional materials related to the decorative arts. These materials bring far-reaching knowledge about the history of Western art from the fourth century CE to the mid-twentieth century into the public eye in addition to supporting the activities of the Frick Collection, including its exhibition program. As at the Morgan Library, the scope of the Frick Art Reference Library catalogue is broader than the works of art at its affiliated museum. Yet, at the Frick, as well as at the Morgan, library and museum shed light on one another while offering separate and unique opportunities for visitors.

Main Reading Room of the Frick Art Reference Library. Photo by Michael Bodycomb. Image courtesy of The Frick Collection.

The Thomas J. Watson Library at The Metropolitan Museum of Art was borne of the same culture, though under different circumstances than the Frick and Morgan. Thomas J. Watson funded the library’s construction as part of the board that organized the Metropolitan Museum of Art and its associated institutions during the 1870s and 1880s. Like the Frick Art Reference Library, one function of the Watson Library is to support knowledge about the Met’s collection of artworks and objects. As is also the practice at the Morgan, one need not visit the Watson Library to see the books, manuscripts, and journals in the Met’s library catalogue, since these items are frequently curated into exhibitions comprised completely of library materials—American artist Tauba Auerbach curated one such exhibition last November. As a glance at the Watson Library Instagram makes obvious, the aesthetic value of texts is a central focus for this library’s staff. As a result, the library is treated as an exciting extension of the museum, critical to continuing discussions about and interest in the collection. Though still a place of solitary and specialized work, the library is integrated into the institution’s public mission and is an asset for the casual visitor as much as to the historian or scholar.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

David H. Koch Plaza. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

There is a reason that the attached museums exist in partnership with each of these libraries. Library materials, sometimes brought out on display for exhibitions in the museums, are often fragile by nature—paper isn’t the most timeless medium. It’s understandable that the Morgan, Frick, and Met all want visitors to stop by their exhibitions before delving into their library collections, but for art historians, curators, curious parties, and artists, these non-circulating collections can help a question squirming at the back of the mind become a full-blown investigation. Art history isn’t just for art historians, and anyone interested in digging a little deeper should visit these three spaces.

—Isabella Kapur, Curatorial Intern