Carmen Herrera sold her first painting when she was 89 years old. Today, at 101, she still works almost every day in her studio. Even though recognition came to her late in life, to call her a late-bloomer would undermine a career spanning over seven decades, a career developed in Havana, Paris, and New York and marked by Minimalist and Op-Art sensibilities even before the movements bearing those labels were established. The exhibition Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight, on view at the Whitney Museum until January 2nd of next year, focuses on a three-decade period of Herrera’s long trajectory, from 1948 to 1978, and features over fifty works that include paintings, sculptures, and drawings. These works represent the steps in the evolution of her groundbreaking and signature style of abstraction, and bring much-warranted attention to an artist now considered among the most important figures of American modernism.

Herrera was born in Havana in 1915 and was educated there as well as in Paris, studying art, art history, and architecture. In 1939, after marrying an American schoolteacher, she left her native Cuba and moved to New York. In 1948, when Abstract Expressionism was blooming in the city’s art scene, Herrera decided to move to Paris. This is where the Whitney show begins as, according to the artist, it was at this point that she began to create her first mature works.

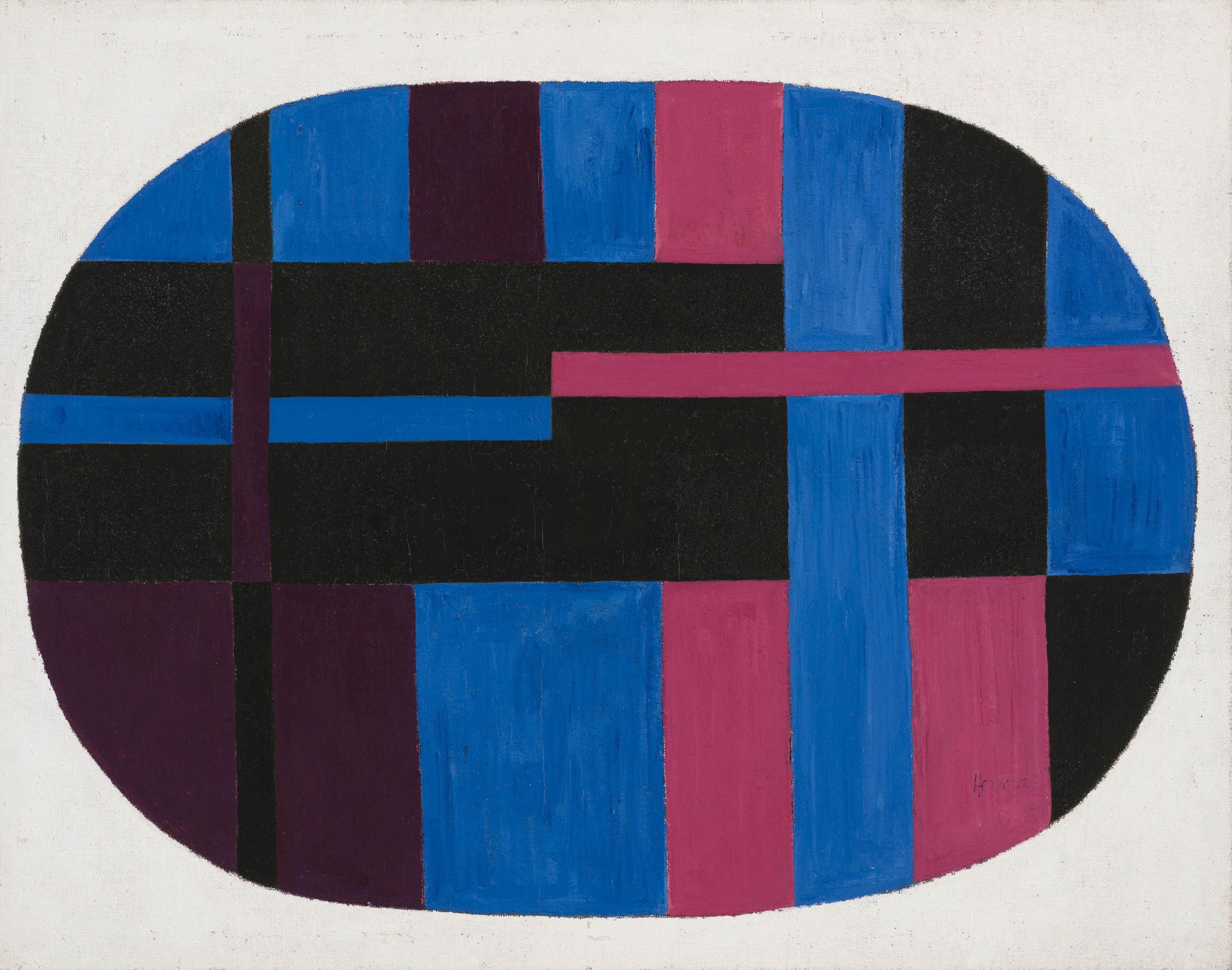

Carmen Herrera, Untitled, 1948. Acrylic on canvas, 48 × 38 inches. Collection of Yolanda Santos © Carmen Herrera

The first section of the exhibition is comprised of works made during her six-year stay in the French capital and during the four years that followed her move back to New York in 1954. In this formative period, Herrera explored different approaches to abstraction and experimented with black-and-white compositions. She deliberately abandoned any style of figuration and aimed instead towards highly geometric compositions using precise lines. She delineated large single color sections ranging in value and contrast to achieve a sense of totality in her paintings. A close inspection of one of these works, Untitled, 1948, reveals the application of thick layers of paint which enhances the tension created at the edges between color sections. After her return to America, she brightened her palette and produced bold, visually captivating works such as Green and Orange, 1958, an early example of Herrera’s incisive style in which all indications of brushstrokes and hand-drawn lines have been removed.

Carmen Herrera, Green and Orange, 1958. Acrylic on canvas, 60 × 72 inches. Collection of Paul and Trudy Cejas © Carmen Herrera

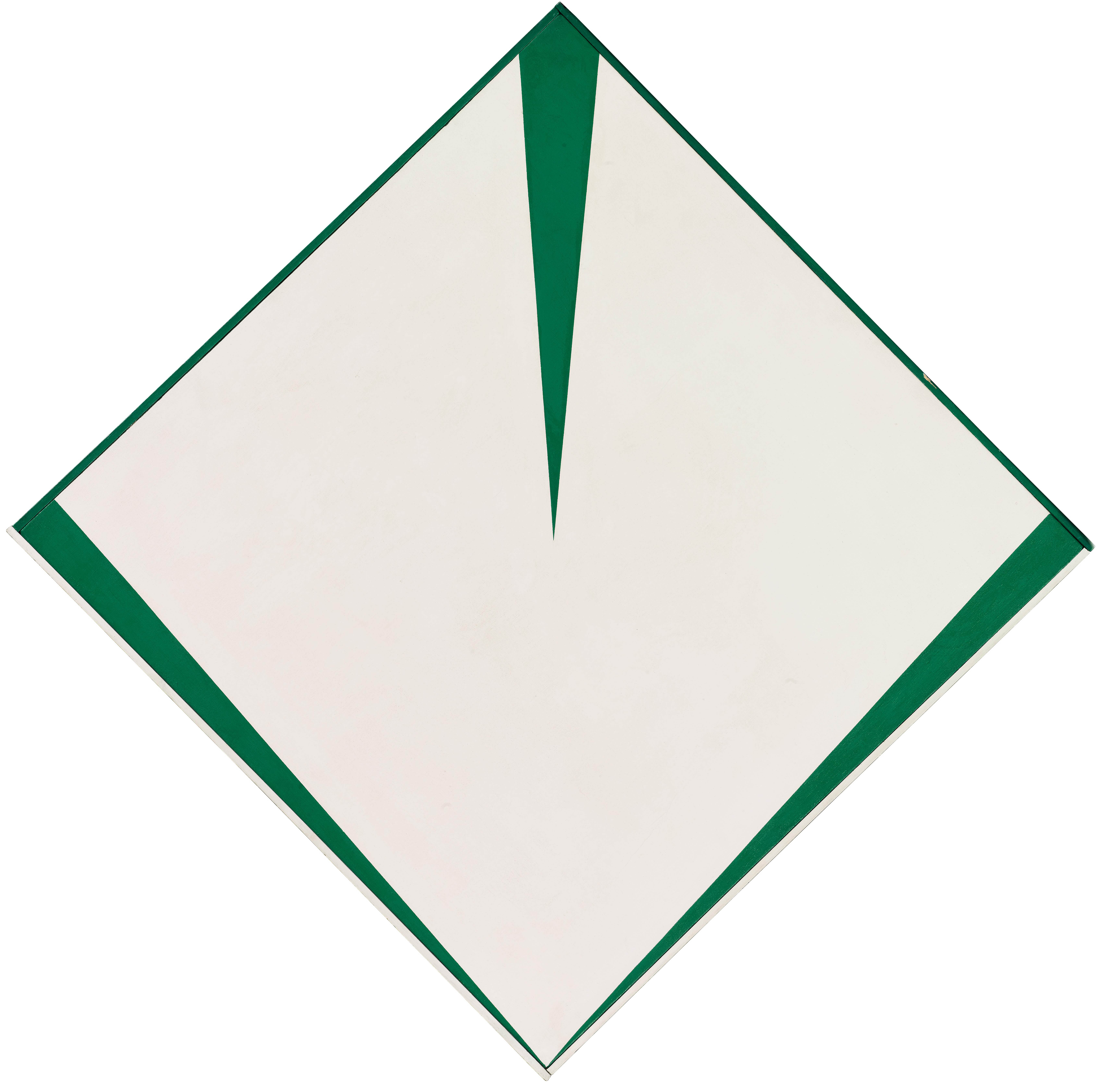

For the second section of the exhibition, which covers works made between 1959 and 1971, curator Dana Miller chose nine paintings from Herrera’s Blanco y Verde series. These works, regarded by the artist as the most important of her career, explore the possible iterations of a very simple set of principles: rectangular compositions in green and white with triangular forms. The triangular shapes in each work are positioned so that they just barely meet at their vertices, creating a sense of stability at each point of near contact. There is no need to get closer to the canvases this time; the viewer, seated on the bench in the middle of the room, can appreciate the moments of supreme tension shared by all the paintings hanging on the surrounding walls. In these works, Herrera also extends her treatment of the painting as a tangible object to the physical structure of the canvas, using the edges of the painting as a compositional tool—for example, in works such as Irlanda, 1965, the composition wraps around the edges of the frame.

Carmen Herrera, Irlanda, 1965. Acrylic on canvas with painted frame, 34 3/4 × 34 7/8 inches. Colección Pérez Simón © Carmen Herrera; photograph © Rafael Doniz

Herrera continued to work with dichromatic compositions throughout the 1960s and 70s, getting rid of all elements outside of the essential in color and form. The third section of the exhibition, Painting, Drawing, and Estructura, 1962–1978, presents compositions that are more refined in terms of technique: the artist constructs complicated relationships using simple forms, achieving what would later be called a minimalist aesthetic. During this period, Herrera produced Estructuras, a series of painted wooden works that, like much of her oeuvre up to this point, challenge the traditional representational character of painting. While sharing the geometric aspect of her earlier compositions, they are also sculptural in nature, thus encouraging the viewer to walk around them. On one of the gallery walls, works on paper show the designs and drawings that Herrera made as preparatory studies for these pieces. Her use of line and consideration of the overall layout reveal the influence of her architectural training from early in her career.

Carmen Herrera, Amarillo “Dos”, 1971. Acrylic on wood, 40 × 70 × 3 1/4 inches. Maria Graciela and Luis Alfonso Oberto Collection © Carmen Herrera

Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight gives the viewer the chance to witness three decades of continuous exploration of geometric abstraction by an artist that perhaps has not been rewarded with the attention she deserves until just recently. By showcasing her work in three chronologically consecutive periods, the exhibition demonstrates the gradual development of Herrera’s unique aesthetic, which has ultimately earned her a place among the most important figures of American modernism.

—Miguel Angel Calderon, Visitor Services Manager, The Drawing Center