Ellsworth Kelly, Wild Grape, 1961. Watercolor on paper, 22 1/8 x 28 1/2 inches. Private collection. © Ellsworth Kelly. Photograph courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

For people seeking a taste of summer without the blazing heat, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exquisite exhibition of Ellsworth Kelly’s plant drawings, on view through September 3rd, provides the perfect occasion. Featuring approximately eighty drawings dating from 1948 during the artist’s time in Paris to his most recent work made in upstate New York, this intimate show reveals another side to the abstract painter that nonetheless makes perfect sense. The plant drawings are essentially contour drawings executed primarily in pencil or pen—although there are isolated spots of color in the exhibition, like a rosy red heap of apples from 1949 (Kelly made a pencil version that same year), a bright green stalk of corn (1959), and a sunshine yellow tulip (also 1959). Kelly has called the plant drawings “a kind of bridge to a way of seeing that was the basis of the very first abstract paintings,”[i] and indeed, both the botanical renderings and Kelly’s abstract compositions aim to strip things down to their basic shapes and contours, supplying the minimal amount of information necessary to understand a form.

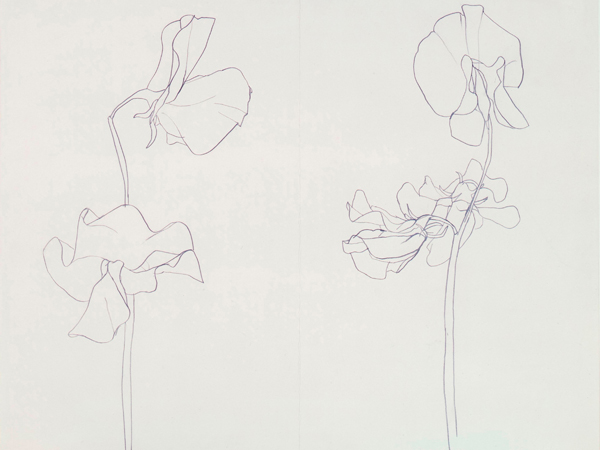

Ellsworth Kelly, Sweet Pea, 1960. Graphite on paper, 22 9/16 x 28 inches. The Baltimore Museum of Art, Thomas E. Benesch Memorial Collection. © Ellsworth Kelly. Photograph courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Still, with their fragile edges and delicate lines, Kelly’s plant drawings have an emotional charge that is distinct from that of his abstract work. Kelly asserts in an interview in the exhibition catalogue that the renderings are “portraits of flowers, not anonymous,” and Kelly’s own predilections and desires seem to emerge as we follow the development of his oak leaves, tulips, lilies, and his ever favored wild grape over time. His gently climbing Wild Grape from 1960 is achingly beautiful while his spiky off-kilter cactus from 1980 is laugh-out-loud funny. This awkward fellow provides a striking contrast with the gently unfurling calla lily placed opposite (2006) and the latter in turn with a pair of scraggly lilies from three decades prior (1980). If these images perfectly capture the changing natural world, they also seem to reflect Kelly’s state of mind while drawing—as he himself tells us, “the most pleasurable thing in the world for me is to see something and then translate how I see it.”[ii]

– Claire Gilman, Curator

[i] Quoted in exhibition catalogue.

[ii] Quoted in wall text.