“Mukherjee’s [works]… attain a level of marvel that edges slightly towards the monstrous,”[1] stated Peter Nagy of Nature Morte. Having seen them first hand, ‘marvelous monstrosity’ seems an apt description.

When Laura [Hoptman, Executive Director] mentioned the other day that a solo show featuring the work of a female Indian sculpture artist had recently opened at the Met Breuer, I was both immediately intrigued and surprised that this was the first I’d heard of it. Indeed, the exhibit—titled Phenomenal Nature: Mrinalini Mukherjee— is quite unorthodox in both its content and execution.

The fact that a Bengali woman is the subject of a retrospective in the US at all is a radical act in itself. One may be surprised to hear that before 2013, neither the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, nor the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum had featured a solo exhibition of a South Asian woman—at most, the work of female South Asian artists had been featured in group shows, such as the 1997 Out of India exhibit at the Queens Museum, which although influential were often reductive and superficial in nature [2]. What’s more, Phenomenal Nature is curated by Shanay Jhaveri, the MET’s first Assistant Curator of South Asian Art in the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art—a role which was, arguably, created specifically for him in 2015 [3]. After joining the MET, Jhaveri almost immediately proposed Mukherjee’s show. As the Met Breuer had been inaugurated with a solo show of Nasreen Mohamedi, he saw it only fitting to feature an Indian artist with a completely opposite visual idiom.

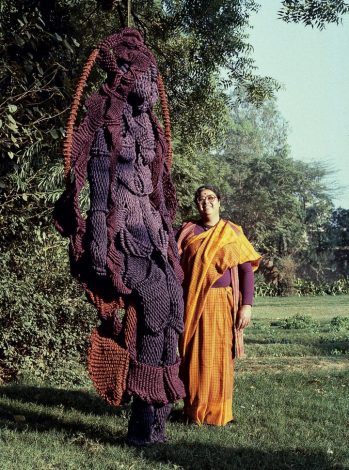

Vriksh Nata (Arboreal Enactment), (3 pieces), 1991–92

Natural and dyed hemp

Left: 87 1/2 × 53 × 19 1/2 in (222 × 135 × 50 cm)

Centre: 93 1/2 × 46 × 27 in (237 × 117 × 69 cm)

Right: 66 × 35 1/2 × 27 in (168 × 90 × 68 cm)

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

© Mrinalini Mukherjee

Photo © Avinash Pasricha.

For Mukherjee herself, who passed away at the age of 65 in 2015, this exhibition of 57 works marks the first comprehensive display of her work in the United States. Especially for a single artist, the scope of her oeuvre is stunningly wide-ranging—from fiber, to ceramic, to bronze—and one can only imagine how much further her work would have evolved, were she still alive today.

Born in Mumbai in 1949 to artist parents, Mukherjee’s childhood was spent both in the foothills of the Himalayas and in Rabindranath Tagore’s own Santiniketan. She went on to MS University in Baroda, India (now Vadodara) where she studied painting, printmaking and mural making; she learned the latter under the influential artist, and her father’s former student, K.G. Subramanyan. Rejecting the Western construct of handicrafts being reduced to a “low art,” Subramanyan encouraged Mukherjee to engage with traditional Indian artistic and craft traditions, especially fiber.

Indeed, in the Western consciousness, the idea of fiber art and knotting often conjures up visions of macrame and other such products of the hippie lifestyle popular in the late 1960s and ‘70s. This handmade countercultural mindset manifested itself in the form of instructional publications aimed at home crafters and hobbyists; the rhetoric of these books would often stress the decorative and functional aspects of these crafts, alluding to “knotting” as being an ancient practice, but divorced from any mention of the cultures it originated from [4]. Thus in its targeting of the white, middle-class female homemaker, fiber art was a largely classist and gendered art form in the US in the 70s.

It is interesting to note, then, that while American artists such as Alexandra Jacopetti and Faith Wilding were working to expand this notion of fiber art in the ‘70s (with their Macrame Park and Crocheted Environment respectively), Mukherjee was around the same time also developing a similar practice, albeit working in near isolation in India.

In straying from the then-dominant tradition of figure painting in India, and in her practice of integrating craft techniques with a modernist visual vocabulary as a South Asian woman, Mukherjee was enacting something quite revelatory. And her insistence on using natural rope and an unconventional loom solidified the intuitive nature of her work.

The fiber sculptures, which mark the beginning of the path through the exhibition and are subsequently sprinkled throughout, are sensual, arresting, organic, and even frightening in nature. Whether jutting from the walls like a bas-relief – such as the piece Nag Devta (Serpent Deity) – or hanging from the ceiling by a thread – as in Rudra (Deity of Terror) – these almost human forms accost the visitor, a sort of corporeal encounter. The exhibit also explores the latter half of Mukherjee’s career in the mid-1990s, when, prompted by a residency at the European Ceramics Work Centre in the Netherlands, she began working with ceramics, eventually taking on bronze in 2003.

From her ceramic works, I was particularly struck by her Night Bloom series, which the exhibition pamphlet describes as being “reminiscent of icons being reclaimed by vines … braiding the human and the vegetal together in a single form.” Seeing these works in person immediately reminded me of similar clay sculptures of Hindu deities I’d made as a child, amorphous in their shape but still recognizable in essence. There resides in her work, then, a timeless quality, hovering between innocence and sophistication. At the same time, however, Mukherjee clarifies that her work is not intended to evoke any specific religious connotation: “My idea of the sacred is not rooted in any specific culture . . . rather it is the metamorphosed expression of varied sensory perceptions.” [5]

Her use of bronze, the artist’s medium of choice in her later years, was likely a decision influenced by having watched her mother model and cast small sculptures in bronze. Mukherjee was able to leverage the uncertainty of sculpting in the lost-wax technique and without the control offered by rope to produce works that seemed to almost defy gravity in their delicacy and acrobatics. Her Palmscape series in particular, although created from innocuous plant fragments collected throughout New Delhi, held an acerbity that seemed almost scorpion-like.

A common theme in descriptions of Mukherjee’s work is a transgression of art-historical categories, and even time itself. Uma Nair states: “They may be fossilised trophies dug from a prehistoric swamp or the robotic armour of an alien orchid creature.”[6] Indeed, her work seems almost anachronistic in its anticipation of art trends and collapsing of time.

Adi Pushp II, 1998–99

Dyed hemp

55 × 44 × 37 in

(140 × 112 × 94 cm)

Collection Amrita Jhaveri

© Mrinalini Mukherjee

Photos © Randhir Singh, 2017

“Mrinalini always enjoyed subverting conventions,” says curator Jhaveri. “She prefers to explore the hidden character of the material, its tactile potential, its ability to express a daring yet subtle eroticism, its power to contain within it an organic fecundity.”[7] Perhaps it is this temporal multivalence that makes her work so subversive.

Phenomenal Nature, curated by Shanay Jhaveri, is on view at The Met Breuer in Floor 3 from June 4 through September 29, 2019.

—Kaira Mediratta, Curatorial Intern

[1] Nair, Uma. “Met, New York: Mrinalini Mukherjee’s Sculptures Will Flourish at the Museum This Summer.” Architectural Digest India. June 04, 2019. Paragraph 9.

https://www.architecturaldigest.in/content/new-york-modern-indian-craftsmanship-sculptures-mrinalini-mukherjee/.

[2] Sharma, Meara. “The South Asian Artists Making Their Mark on the Western Scene.” The New York Times. December 28, 2018.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/28/t-magazine/south-asian-artists.html.

[3] Lowry, Vicky. “Shanay Jhaveri Makes His Curatorial Debut at the Met.” Galerie Magazine. Spring 2018.

https://www.galeriemagazine.com/the-met-museum-shanay-jhaveri-makes-his-curatorial-debut/.

[4] Bryan-Wilson, Julia. Fray: Art and Textile Politics. University of Chicago Press, 2017. Pp. 20-21.

[5] Phenomenal Nature: Mrinalini Mukherjee. The Met Breuer, 2019. Exhibition guide.

[6] Nair, Uma. Paragraph 9.

[7] Nair, Uma. Paragraph 2.