This conversation between artists Mickalene Thomas and Judith Bernstein is excerpted from our catalog for Judith Bernstein’s ongoing exhibition Judith Bernstein: Cabinet of Horrors, on view through Sunday, February 4, 2018.

MT: How long have you been in this live/work space?

Judith Bernstein: I have been here fifty years. I don’t own the space. It’s actually rent stabilized. Well you know what happened? I graduated from Yale and I came to New York and I looked in the Village Voice to try to find a place to stay, and I found this loft. So, I just remained here. It was too bad that I didn’t have some money in the 70s, because I graduated from Yale in ’67. So in the 70s, you could have bought something really cheap, but I still didn’t have the money to buy it at that period of time. And also, the foresight to beg around or whatever you have to do to get that. But nevertheless, now I can actually afford to stay in New York, but that became a reality only very, very recently.

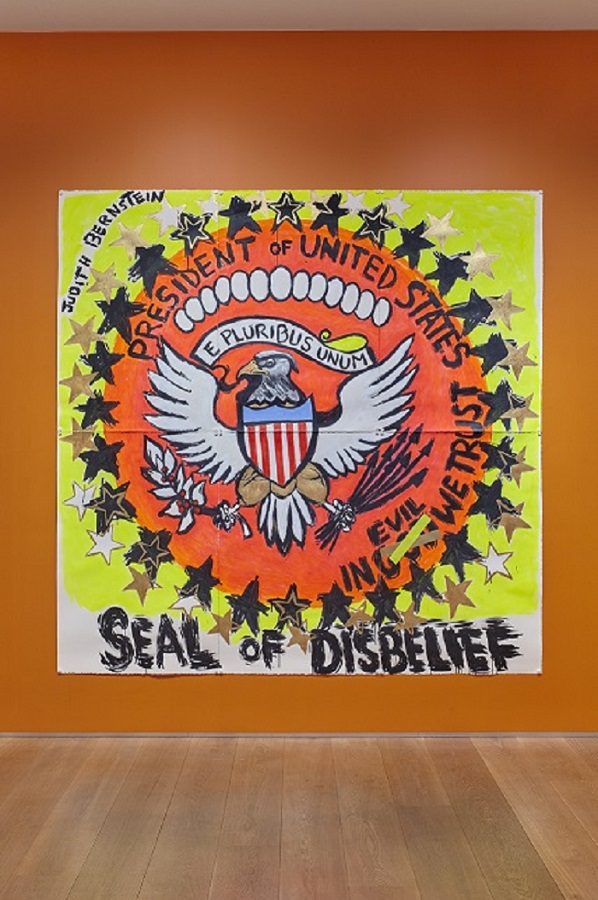

Installation view of Judith Bernstein: Cabinet of Horrors, The Drawing Center, 2017. Photograph by Martin Parsekian.

MT: Who were some of the artists you hung out with after graduate school? Who were your friends? What was it like for women artists during those times? Where’d you go? What was your New York City like then? Because I know what it was like for me after I graduated in 2002. Could you talk about your experience as an artist during those days?

JB: Well, I’ll tell you frankly, I was kind of on tenterhooks, because it’s very hard to make that transition coming from an academic situation where I didn’t realize the prejudice against women artists. Don’t misunderstand me. But it wasn’t anything that was any big deal in comparison to the brick wall that you hit, by the way, when you came to New York at that time. And it’s funny, because I went to Penn State as an undergraduate. There were three men to every woman at that time. That’s not how it is now. Then when I went to Yale, it was an all-male school. In 1967 when I graduated, that was the first year they allowed women as undergraduates. As a graduate student, there were only like three women in my class, and all the rest were guys. It was a different time frame; now the gender makeup of academic institutions has really shifted. Absolutely—definitely more women than men in these programs now. Women are dominating at a large number but are still underrepresented in galleries, museums, and private collections. When I came to New York, there were a lot of women who were like me. They had gone to graduate school, they were smart. They wanted access to the system. So what could they do? Start a gallery! There was Barbara Zucker, Dotty Attie, Mary Grigoriadis, and a woman named Sue Williams. Not the Sue Williams that you’re familiar with. Lucy Lippard was a critic, which probably I’m sure you know. But anyway, she had a file of a lot of women artists. So they went to her studio and they looked at the file, and they picked people and went on studio visits to choose artists that they wanted to work with. They wanted to start a woman’s gallery, the first woman’s gallery. The first women’s gallery—that became A.I.R. and that was in 1972. Such a long time ago.

Installation view of Judith Bernstein: Cabinet of Horrors, The Drawing Center, 2017. Photograph by Martin Parsekian.

JB: When were you born?

MT: 1971, in Camden, New Jersey. Raised in East Orange, Hillside, New Jersey. Moved around quite a bit.

JB: Wow, wow, wow, wow. You see, it was a million years ago. They went to studios and that’s how it all started. Women didn’t have options to show, there was such a wall. Everywhere you’d go, there’d be galleries that would be all male, and that were not receptive to me and the work I was doing.

It was interesting because when they first started A.I.R., they were trying to figure out a name. Howardena Pindell was part of that, and Howardena actually was a roommate of mine when I was at Yale a long time ago. Anyway, she suggested “Jane Eyre,” and the gallery said “A.I.R.” I had suggested at the time, “TWAT: Twenty Women Artists Together.”

MT: I love that. They should have used TWAT. Did they use it?

JB: No, unfortunately not, but A.I.R. turned out to be very good because it was a code name for “artist in residence.” Back then there would be a sign at building entrances that would say “A.I.R.” to let the fire department ensure that if something happened, they could get in, get you out. Then, the people I was hanging out with, Joyce Kozloff, who else? I was friendly with Loretta Dunkelman, Jackie Winsor. I was friendly with Joan Semmel—a lot of the feminists at that time. Nicole Mouriño: What about Martha Wilson? Pat Steir? Oh, Martha. We became friends in the ’80s, and she has been very supportive, and a collector of my work.

MT: Are there any artists that you wish you would have gotten to know, or do you regret, because either they passed? Or you know, their connection never happened?

JB: Yes, that’s a really good question. Let’s see, Nancy Spero, I was friendly with, but I would say we weren’t super close. Louise Bourgeois, I knew, by the way, and Louise was great. She was very, very funny and acidy in terms of humor, and she was really a hoot. I also missed out on meeting Richard Lindner, that would have been interesting. There was a group of women artists separate from A.I.R. that were “fight censorship” women. Louise was part of that, Anita Steckel, and who else? Joan Semmel. It was like the precursor to the Guerrilla Girls.

MT: Are you a Guerrilla Girl?

JB: Yes, yes. Well, I’m not now, but I was for a long time.

Installation view of Judith Bernstein: Cabinet of Horrors, The Drawing Center, 2017. Photograph by Martin Parsekian.

MT: You have been confronting and questioning male patriarchy for a long time with your drawings using male phalluses. When did you start to work with this subject matter?

JB: Pop Art was in the air and I thought of screws, screwing, and being screwed. Well, how did Anita put it? She said, “If a penis is wholesome enough to go into a woman, it should be wholesome enough to go into a museum” [sic]. That was just hilarious. But we had a good time with the group. We were photographed by John Franco, and were on some radio shows—stuff like that. Frankly, the art world was very small in comparison to what it is now. We got together with people that were like-minded. But each artist’s sexual subject matter was very different, since sex is such a raw or explosive topic anything sexual gets put into one category, when the agendas are very different. My own work was political and sexual, and I was using the cock as an antiwar image. It was also feminist, and of course, about sexuality.