Drawing is an essential part of architectural practice. In the digital age, most drawing is done through computer-aided design software, but the hand of the architect is still crucial. In Frank Lloyd Wright’s day (1867–1959), of course, all drawing was done by hand. Wright, however, had a special appreciation of his drawings, not just as design aids and construction documents, but as elements of branding and publicity, as well as aesthetic objects in themselves.

Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive, now on view at The Museum of Modern Art, presents more than 450 works from the Frank Lloyd Wright Archives, comprising drawings, architectural models, films, television broadcasts, and more. The exhibition engages the work of the renowned and prolific architect on a wide variety of fronts. In doing so, it enables the visitor to see Wright’s understanding of the importance of his architectural drawings, and the canny uses to which he put them.

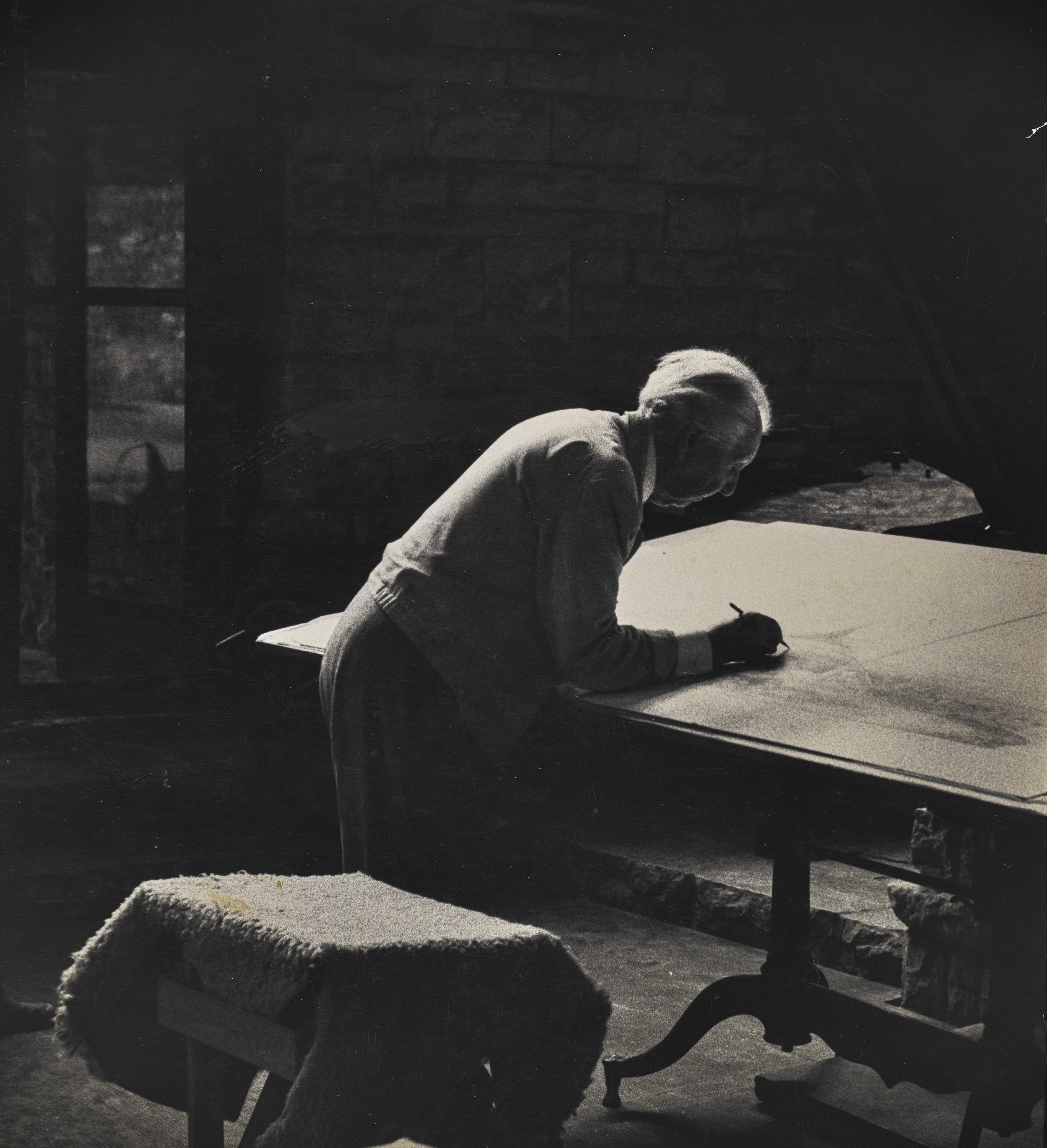

Unknown photographer. Frank Lloyd Wright. n.d. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York) © 2017 Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, AZ. All rights reserved.

Wright began his career as a draftsman in the firm of Adler & Sullivan, and an early drawing of the gate to the Wainwright Tomb in St. Louis, in Wright’s own hand, shows his mastery of Louis Sullivan’s intricate, curvilinear ornament. Wright’s elevation drawing of his design for the Milwaukee Public Library and Museum (1893), produced from his independent practice after leaving Adler & Sullivan, is a fairly straightforward rendering of a neoclassical design. However, a pair of drawings done slightly later by licensed architects working in Wright’s Oak Park studio show a growing awareness of the opportunities presented by architectural drawings beyond the studio. They also illustrate the evolution of the Wright studio style under the influence of the Japanese prints that Wright admired and collected.

Installation view of Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 12–October 01, 2017. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar.

The rendering of the Thomas House by Birch Burdette Long and the perspective drawing of the DeRhodes House done by Marion Mahony—one of the first licensed women architects in the United States—show a dramatic use of negative space and dynamic framing that are clearly derived from Japanese printmaking. It is apparent that these renderings were intended to evoke an emotional response as much as they were intended to convey architectural information. The studio was using aesthetic tools to evoke feelings about Wright’s buildings and to contextualize his architecture within Western interpretations of Eastern traditions that bring built structures into harmony with landscape and nature. The drawings are visual representations of Wrightian concepts and show in an immediate and instinctive way what Wright sought to accomplish in his practice.

Comparing these drawings with a much later (1930) perspective and detail of the Larkin Building shows a marked change in the Wright Studio style of drawing. This difference reflects Wright’s changing motivation for promoting his practice and ideas. This Larkin detail is done in a spare, black-on-white style, devoid of the landscape elements in the earlier drawings that establish a setting and the foliage that indicates the natural world. Austere and self-consciously “modern,” this drawing and others like it evoke the International Style at a time when Wright attempted to both undermine architectural modernism and position himself as its avatar.

The even later series of drawings of Wright’s proposed Mile-High Illinois tower, proposed in 1956 at a separate stage in his career, are incredibly dramatic and likely useless as architectural elevations. Vertical in orientation, and done on overlong, narrow sheets of paper, these drawings position his needle-like tower rising above a tiny Chicago, like a redwood soaring over a forest of saplings. Their intent is to evoke in the viewer the sublimity of Wright’s grand expression of architectural power and position his mile-high tower as the epitome of forthright American optimism.

Installation view of Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, June 12–October 01, 2017. © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Jonathan Muzikar.

Throughout his career, Wright used architectural drawings not only as planning and construction tools, but also to further his architectural program. As the publication of the Wasmuth Portfolio in 1910 shows, he was very conscious of his drawings as important elements of a campaign to revolutionize capital-A Architecture. MoMA’s Unpacking the Archive exhibition makes it clear how important drawing was to this great American architect.

Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive is one view at MoMA through October 1, 2017. The exhibition was organized by The Museum of Moder Art, New York, and Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

—Champ Knecht, Deputy Director for Administration, The Drawing Center