Les graveurs du XIXe siècle, a guide to printmakers published in 1885, describes Henri-Charles Guérard as an artist characterized variously as a “modernist, Impressionist, ‘Manetist,’ one who depicts landscapes and seascapes, a japoniste, one who indulges in fantasies, an alchemist, an essayist, with imagination constantly at work, having in his head a bouquet of fireworks that bursts into thousands of caprices.” Throughout his career, Guérard put his wide-ranging abilities toward the task of establishing printmaking (and even printed ephemera) as high art. On view at the New York Public Library’s Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, A Curious Hand: The Prints of Henri-Charles Guérard (1846–1897) presents nearly ninety works on paper from the library’s own Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs that speak to Guérard’s role as printmaking’s advocate in late-nineteenth century Paris.

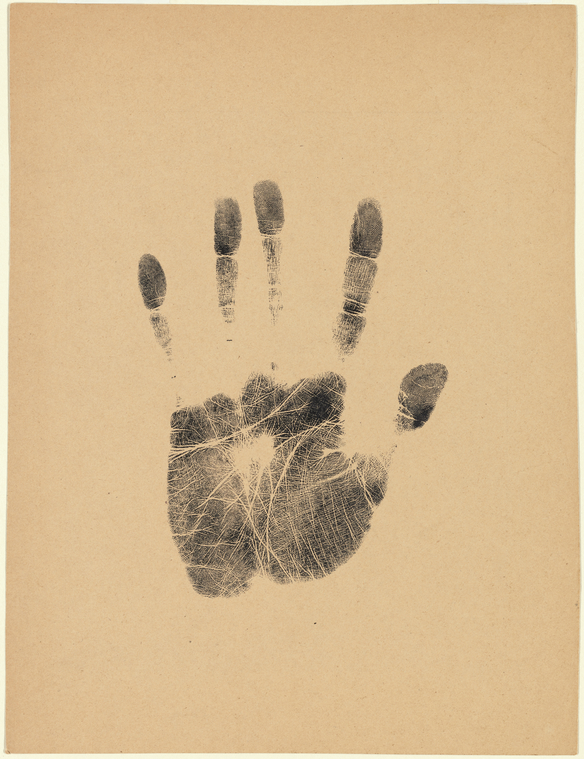

Henri-Charles Guérard, Imprint of the Artist’s Left Hand, ca. 1885. Unique nature print. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

As an allegorical representation of the exhibition, an imprint of Guérard’s left hand (c. 1885) stands at the galleries’ entrance. Though the first part of the exhibition highlights Guérard’s reproductions of works by masters such as Rembrandt and Velázquez, the intimacy and, indeed, inventiveness of Guérard’s handprint demonstrates the artist’s regard for original printmaking as commensurate with other genres of fine art—since, as the critic Roger Marx concluded in 1889, printmaking, like painting, is created by the artist’s hand, aided but not supplanted by mechanical technique.

Henri-Charles Guérard, After Rembrandt van Rijn, Docteur Faustus, ou Le Microcosme [Faust], 1875. Etching. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

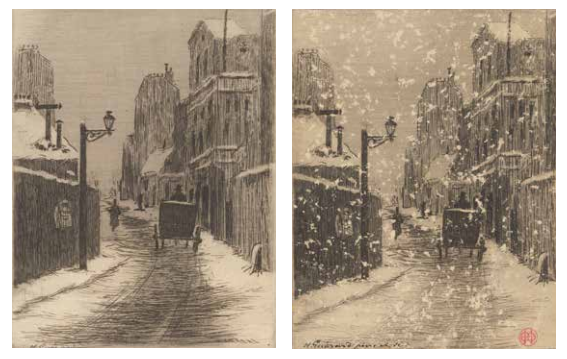

These views are underscored by Guérard’s position as a founder of the Société des peintres-graveurs français (est. 1889), a circle of artists who aimed to raise printmaking’s standing. Guérard’s own experimental practice held this goal to task; in an etching entitled La Rue Chevert (before 1888), for instance, Guérard removed pieces of his print’s surface to give the scene a wintry effect. Such desire to subvert existing conventions in French art points to the early influence of Edouard Manet, whom Guérard worked with early in his career, creating reproductions (perhaps better described as ‘translations’) of paintings such as Dead Toreador (1864) and The Boy with Soap Bubbles (1868–69).

Henri-Charles Guérard, La Rue Chevert, before 1888. Left: Etching and aquatint; Right: Etching, aquatint, and toolwork. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Guérard’s extensive engagement with Japanese subjects is also prominently featured in A Curious Hand. Drawing inspiration from manga, whimsical sequential woodblock prints, by the Japanese Edo-period artist Hokusai, Guérard completed nearly 200 illustrations for the publication L’Art japonais, a publication that added to the wave of interest in Japanese culture in late-nineteenth century France, known as japonisme. Though japonisme is considered Orientalizing in essence, Guérard’s nuanced study of his subjects suggests a deep respect for Japanese culture; the artist’s prints neither focus exclusively on attractive Japanese women nor depict East Asia as an a-historical utopia, but rather delve into the nuances of Japanese techniques and folk subjects. There is no doubt that Guérard also viewed the popularity of Japanese woodblock prints as a boon to printmakers eager to assert the legitimacy of their genre.

Henri-Charles Guérard, L’Assaut du soulier [The Assault of the Shoe], ca. 1888. Etching, drypoint, and aquatint with roulette in pink. Figures in this image resemble figures found in Hokusai’s manga. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

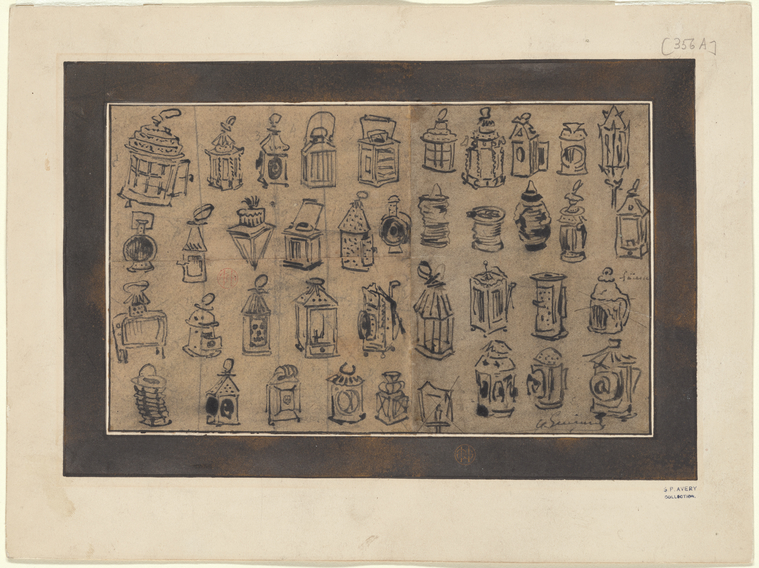

Far from the austerity of Guérard’s early reproductive prints, his later works highlight the personal (and somewhat eccentric) inclinations of the artist who frequented the zoo and maintained a protracted collection of lanterns, regarded as increasingly outmoded commodities. That Guérard introduced reflections on his own experience into his oeuvre suggests the artist’s interest in using biography as a means to assert printmaking as a valid from of artist expression and contemplation about life.

Henri-Charles Guérard, Composite drawing of the artist’s lamp collection, 1876. Pen and ink. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

In A Curious Hand: The Prints of Henri-Charles Guérard (1846–1897), the New York Public Library presents an artist who never ceased to view printmaking as a genre with singular merits. Even in Guérard’s numerous examples of printed ephemera—maps, menus, addresses, fans, calendars, and calling cards—the artist chose to use intaglio, a technique more esteemed than lithography, which was typically used to produce such items. In A Curious Hand, one finds an artist unafraid of experimenting with media, encountering cross-cultural exchange, and referencing his personal experience; an artist who was equal parts printmaker and rebel.

—Amber Moyles, Curatorial Assistant

A Curious Hand: The Prints of Henri-Charles Guérard (1846–1897) is on view at the New York Public Library’s Stephen A. Schwarzman Building (476 5th Ave, New York, NY) until February 26th.