Unfinished artworks are unfinished either through circumstance or intent. Most often the death of the artist leaves the work unfinished, but sometimes the artist abandons the work, never having achieved to his or her satisfaction its complete realization. Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible, at the Met Breuer through September 4th, presents unfinished works, mainly in the Western tradition, from the Renaissance to the twenty-first century. The curators Kelly Baum and Andrea Bayer explore the idea of “unfinishedness” in art and what it might mean as a phenomenon and also as a strategy.

Many of the works in the exhibition from the Renaissance and Baroque periods are unfinished because of circumstance, but in the nineteenth century, unfinishedness began to be seen as a tool for the artist to use in her or his project. Certainly the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists were comfortable with allowing the eye of the viewer to “finish” the work. And in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, as artists grew increasingly comfortable with unfinishedness, they began to explore boundlessness, seriality, and decay—all ways to problematize any notion of a work being “finished.”

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), “The Agony in the Garden,” 1558–62. Oil on canvas, 69 1/2 x 53 1/2 inches. Collection of Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid © Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

A number of the earlier works in the exhibition—those from the Renaissance particularly—exhibit a non finito aesthetic, as it was known. Broadly and loosely painted, non finito uses the vivacity of an unpolished surface and immediacy of a sketch as a counter to the fully-worked and polished ideal. Titian and Tintoretto were two masters of the non finito, and a work such as Titian’s The Agony in the Garden shows the less resolved technique used to great effect. The areas where the light does not fall in the scene are less worked, looser, less finished; the resolution being less complete, as it would be to the eye of anyone in the scene. The non finito aesthetic is used to encourage the active engagement of the viewer’s imagination.

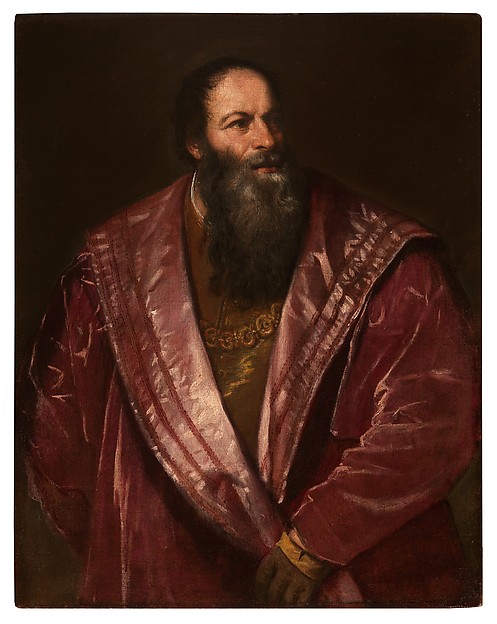

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), “Portrait of Pietro Aretino,” 1545. Oil on canvas, 38 1/16 × 30 9/16 inches. Collection of Palazzo Pitti, Galleria Palatina, Florence. Scala / Art Resource, NY.

Another work by Titian, his Portrait of Pietro Aretino, is one of the first in a series of unfinished portraits in several galleries of this massive exhibition. This portrait, commissioned by Aretino for Cosimo de’ Medici, has a rough surface that Aretino thought a sketch more than a finished painting. Yet he knew that the portrait, while not fully finished, has a “marvelous strength” and pulses with life. Aretino’s reaction to his portrait mirrors my own experience in viewing many of the portraits in the exhibition.

George Romney, “George Romney,” 1784. Oil on canvas, 51 3/8 x 41 inches. Collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London; purchased 1894. © National Portrait Gallery, London / Art Resource, NY.

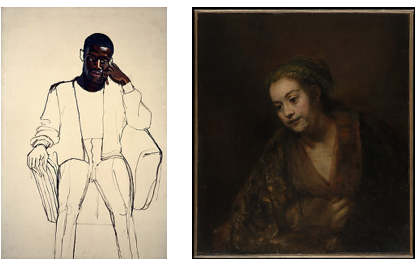

George Romney’s arresting self-portrait of 1784 shows a fully-realized face and crossed arms, with the barest sketch of a body, but it captures a moody and determined artist at the height of his powers. James Hunter Black Draftee, whom Alice Neel met by chance and who sat for her only once before he was scheduled to leave for Vietnam, reveals his apprehension and uncertainty as his draft date approaches. And Rembrandt’s portrait of his companion Hendrickje Stoffels in its intimacy and freedom from “finish” shows everything one needs to know about the relationship between the artist and the subject. To my twenty-first century eye, all of these works are fully-realized portraits—they convey vivid impressions of the sitter whether finished or not.

LEFT: Alice Neel, “James Hunter Black Draftee,” 1965. Oil on canvas, 60 x 40 inches. Collection of the COMMA Foundation, Belgium © The Estate of Alice Neel, Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London. RIGHT: Rembrandt (Rembrandt van Rijn), “Hendrickje Stoffels (1626–1663),” mid-1650s. Oil on canvas, 30 7/8 x 27 1/8 inches. Collection of The Met; gift of Archer M. Huntington, in memory of his father, Collis Potter Huntington, 1926.

Rembrandt is said to have stated “A work is complete if in it the master’s intentions have been realized.” And Matisse claimed that a work of his is finished “when it represents my emotion very precisely and when I feel that there is nothing more to be added.” George Romney sent his self-portrait as a gift to his friend William Hayley “as is.” Alice Neel signed her portrait of James Hunter on the back, declaring it finished. In these two cases at least, the artists recognized that the portrait was finished in terms of their artistic aims, whether or not its technique was perfectly finished in the academic sense. And this is the key to why so many of the portraits in the preceding galleries seem to me to be “finished.” They have achieved the artistic object of portraiture—to capture the sitter in some essential way.

A twenty-first century viewer has taken an artistic journey already, from the non finito of the Renaissance, mediated by the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists and their quest to paint as the eye sees, through Turner and his expansive, immersive storms and sunsets, through Cubism and Abstract Expressionism and Minimalist and Conceptual Art with their explorations of boundlessness, seriality, and decay, to a place of observation that is more comfortable with the unresolved than ever before. Lack of resolution, inconclusivity, and ambivalence are now part of the aesthetic experience, and allow a twenty-first century viewer like myself a greater appreciation of “unfinishedness” than I might have without the intervention of art history.

—Champ Knecht, Deputy Director for Administration at The Drawing Center