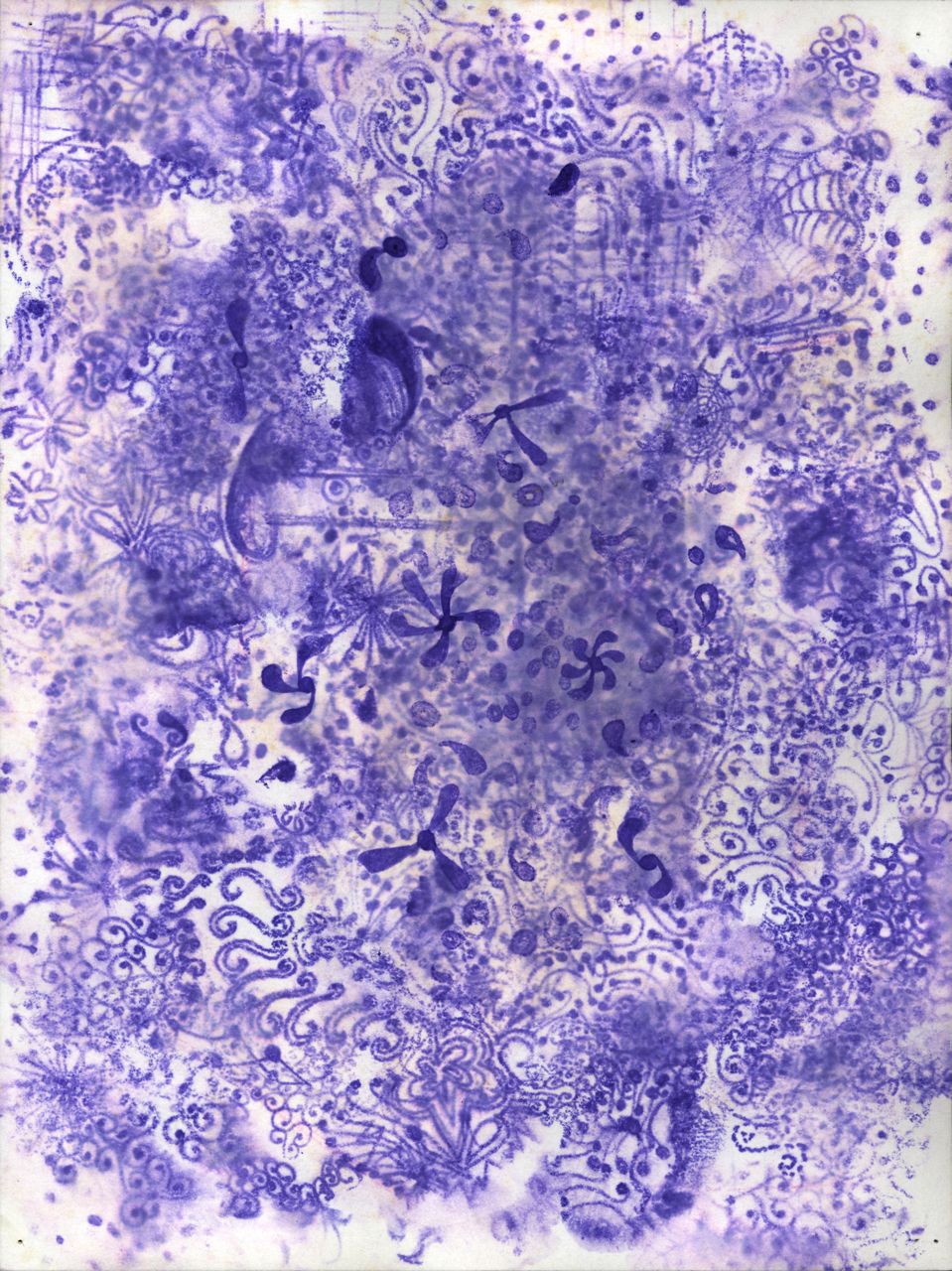

Felice Koenig shapes her paintings by applying layer upon layer of color—each layer an accumulation of resonant fields of dots. What is not immediately apparent in this intensely material practice is her deep dedication to love. Each painting takes months to complete, and during this time Koenig focuses on an affirmative vision. In her most recent piece, Double Embrace, she imagines a human being held by another, cradled in the cosmic ether. As she says, “One is temporal, the other endless.”

Felice Koenig, detail of Double Embrace, 2015. Acrylic on polystyrene, 24 x 24 x 4 inches (61 x 61 x 10 cm), from the Sculpted Form Series. Courtesy of the artist.

In Koenig’s current exhibition Drawing Together, she invites the public to create with her, using the simple tools of youth: paper and colored markers. Sitting opposite one another and working simultaneously on the same piece of paper for ninety minutes, the goal is to use play as a vehicle to create new bonds. The bridge between the seeming contradiction of her rarified, solitary work and her desire to contribute to the world’s betterment emerged by chance one day while I was visiting Koenig’s studio. She asked if I wanted to do a collaborative drawing. It had been a pastime since she was a small child, and throughout her life it continues as a form of connection with her intimate circle. After this interaction, I suggested she draw with a wider range of people as a means of merging abstraction with her social values. Thus, this project was born.

My own curatorial practice advocates for love, and also an understanding of these familial, romantic, and community bonds as built from moments of heartfelt exchange. In 2013, I organized More Love: Art, Politics, and Sharing since the 1990s at the Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This exhibition brought together thirty-three conceptual artists, including Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Janine Antoni, Emily Jacir, and Antonio Vega Macotela, who make political art by emphasizing emotional ties and/or fostering participation. One of the exhibition’s key tenets was feminist theorist Luce Irigary’s call for a “wisdom of love,” a form of non-hierarchical knowledge exchange. Rather than the traditional Western “love of wisdom,” she argues for “a philosophy [which] joins together the body, heart, and the mind.”

To capture what is ephemeral, cumulative, difficult to record, and sometimes impossible, many of the artists in More Love amassed collections of tender, fleeting, reciprocal actions. A 175-pound pile of candy becomes a gift to the viewers, one piece at a time. The politically less heard contribute their words of love for campaign-style buttons. Artists act as surrogates for the imprisoned; one of them asking the inmates to create a symbolic diagram of his substitute encounters around Mexico City, 365 time exchanges in all. A forensic artist sketches the first loves of brave More Love visitors. Two thousand, two hundred, forty-eight butterfly kisses with Cover Girl Thick Lash mascara between two sheets of paper become fields of affection, flirtation, child’s play, and longing. Again and again, drawing offers the artist and participants a way to pay attention, document, and remember fragile instances of intimacy.

Jim Hodges, Untitled, 1992. Saliva-transferred ink on paper, 12 x 9 inches (30.5 x 22.9 cm). Collection Susan Harris. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels. © Jim Hodges.

With his saliva drawings, Jim Hodges, a poetic alchemist, collects fleeting interpersonal interactions by sketching flowers, spider webs, and endless doodles on disparate scraps of paper. He then covers a piece of paper with his saliva, and uses it to make mono-print transfers of those images next to and on top of each other. Recalling the Bazooka bubble gum tattoos of his childhood, Hodges finds a method to convey the sensuous touch, coupling, body tracing, and “misinformation” between two people. Made at the height of the AIDS epidemic, this series of works transforms a fearful bodily substance into something unpredictable, yet beautiful. Likewise, Koenig’s collaborative drawings also trace her experience with her partners. As C. Allan Ryan, an eighty-six year-old retired telephone executive, remarked in reference to his drawing with Koenig: “Can you recall the best party you ever went to, or the best time you ever had on vacation, or the best couple of hours you spent with somebody? That’s what this will tell me in retrospect.”

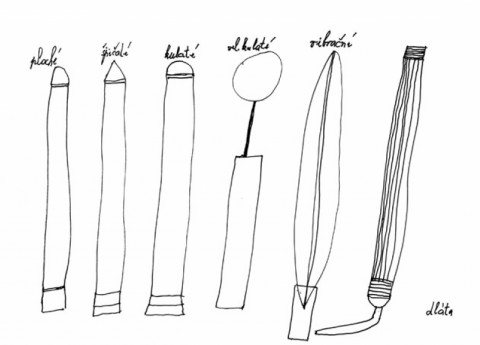

Kateřina Šedá, It Doesn’t Matter, 2005-07. Grandmother’s drawings. 17 ¾ x 24 ½ inches (45 x 62.5 cm). Courtesy of the artist.

Czech artist Kateřina Šedá used drawing to re-engage her grandmother, Jana. She had given up on life after retiring, ceasing to cook, clean, or shop. To almost every question she replied: “It doesn’t matter.” Šedá asked her to depict every tool in the hardware store where she once worked, the remaining focus of her interest. The 521 pen-on-paper documents of wrenches, pliers, and all manner of knives, brushes, and infrastructure parts, became an exquisite handmade catalogue. Her depression abated; the act of drawing a tonic. With the innocent line of the untrained applied to these industrial objects, the works became marvelous abstractions. Similarly, Koenig offers her collaborators a page for reflection. She mirrors their squiggles and dashes, and in so doing, draws them out.

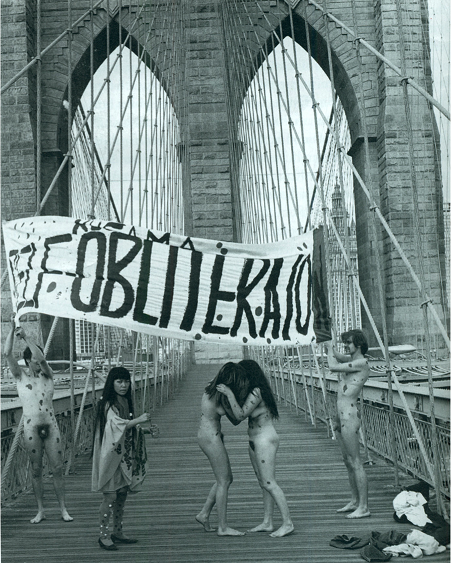

Yayoi Kusama, Self-Obliteration Happening, Brooklyn Bridge, New York, 1968. Performance. Courtesy Victoria Miro Gallery, London; Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo and Yayoi Kusama Studio, Inc. © Yayoi Kusama.

Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama wants to see the world through an all-embracing veil. Her Infinity Nets are vast abstract canvases full of interlocking patterns of cells, reminiscent of Koenig’s matrix of dots. An early figure in feminist, minimalist, and performance art movements, Kusama went on to cover entire rooms and even the landscape with her signature spots, literally painting animals and the water in a pond in her 1967 film Self-Obliteration. The next year she brought this idea of an infinite togetherness to happenings in protest of the Vietnam War. In highly publicized events, she would occupy public space, inviting participants to disrobe and then cover their bodies with equalizing polka-dots in five colors. Scholar Jonathan Katz discusses these gatherings as symbolic of the 1960’s form of love, where difference was deemphasized in favor of commonality. With her touch, he says, “Kusama transforms everyone into more or less the same order of being,” and then harnesses that “… as the route to collective freedom.” While clearly a descendent of this expansive mark-making pioneer, Koenig takes her repetitive, loving gestures off the canvas and into the world, one meditative encounter at a time. Reflective of today’s current decentralized community structure, she builds her field of love with a cascade of individuals. Their drawn interactions become this network’s only trace.

Documentation of Felice Koenig and Gerald Mead drawing Catalyst Sweep Embellish from

Felice Koenig and CS1 Curatorial Projects, Drawing Together, 2015. Social engagement piece comprising a series of 14 x 11 inches (35.5 x 27 cm) colored marker and paper drawings co-created in 90-minute sessions with individuals at Big Orbit Gallery in Buffalo, NY. Courtesy of the artists. Photo by Claire Schneider.

When sitting down to draw with Koenig in a small replica of her studio, her drawing partner is offered a blank piece of paper amongst a sea of Prismacolor and Stabilo markers. Koenig waits for her collaborator to make the first mark, and then mirrors and embellishes his or her gestures. If the person sketches in the corner of the page, sweeps lines across it, or creates waves of dots, so does she. If the participant does not know how to start, Koenig will visually respond to a first word, a current thought or feeling, which she had asked the person to hold in his or her mind as they began. She waits for her collaborator to rotate the piece of paper, one of the few directions, and the volley of marks continues; the sheet is turned again, and the artists are “off cruising, connecting, drawing. All clicked in.” It’s like jazz musicians riffing off one another. There is a mutual feeling of being gifted. Time stops. The creative self is alive in the joy of making without the care of a final product. As one, initially nervous librarian said, “I think the experience dusted off a part of my brain, because that evening I stopped at my piano, sat down and played—for the first time in ages.”

Felice Koening and Rodney Taylor, Conversation Having Humanity, from Felice Koenig and CS1 Curatorial Projects, Drawing Together, 2015. Social engagement piece comprising a series of 14 x 11 inches (35.5 x 27 cm) colored marker and paper drawings co-created in 90-minute sessions with individuals at Big Orbit Gallery in Buffalo, NY. Courtesy of the artists. Photo CEPA.

Drawing balances—it is both concentration and release. Drawing Together shifts two people from a typically lone state into a profoundly sincere dialogue. The final drawing is a celebration of this new connection. The beautiful vibrating energy of the universe, which Koenig offers to viewers in her painting, is now more action than object. As the founders of the website Learning to Love You More, artists Miranda July and Harrell Fletcher, wrote: “the best art is like an assignment; it is so vibrant that you feel compelled to make something in response…in the same way that the ocean gives the assignment of breathing deeply, and kissing instructs us to stop thinking.” In the ever pinging now, Drawing Together supports presence, togetherness, and play, and in so doing, advocates for reparative communion.

—Claire Schneider is Director and Founder of CS1 Curatorial Projects and is currently organizing Felice Koenig: Drawing Together on view at CEPA Gallery’s Big Orbit Project Space in Buffalo through May 16. Her 2013 exhibition More Love: Art, Politics and Sharing since the 1990s, Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, won an American Association of Museum Curators Award for Best Exhibition and was accompanied by a 240-page catalogue.