Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696-1770) is best known as the most inventive and original fresco painter of the eighteenth century; his son, Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo (1727-1804), followed in the father’s footsteps. The exhibition Tiepolo Caricatures from the Robert Lehman Collection, closing this Sunday, September 28th at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, examines both artists’ lesser-known caricature studies. The exhibition includes drawings by Giovanni Domenico featuring the Commedia dell’arte character Punchinello, and drawings of people viewed from behind by Giovanni Battista.

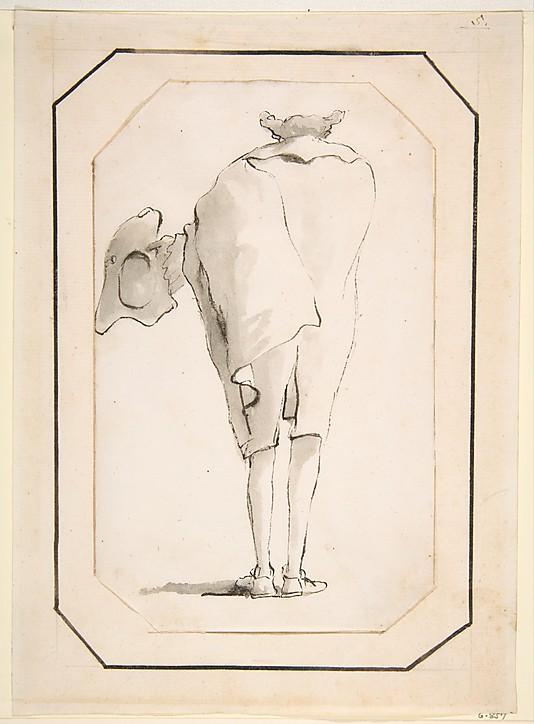

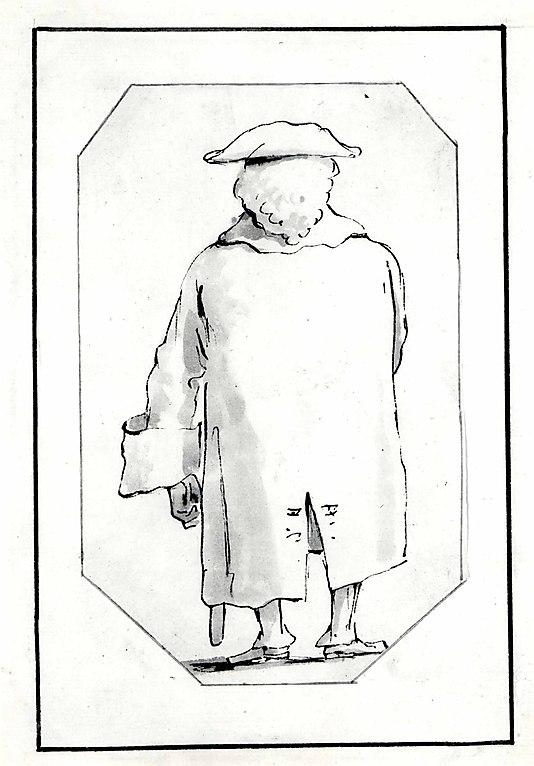

The “seen from behind” caricatures are very minimal drawings, in which figures are outlined with just a few strokes of pen. Light grey ink wash merely hints at volume. The Punchinello drawings are more detailed and developed compositions, but they still maintain a rather loose, playful approach of a quick wash with line details drawn fluidly with pen; the artist chose to work in shades of brown ink, which seems to accentuate the playfulness.

The curators of this small exhibition do not attempt to provide an in-depth explanation of the social and political significance of these images, and as a result some of the symbolism is probably lost on the modern viewer. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo was an astute social observer, and certain types from contemporary life enliven his religious and mythological frescoes. Just as iconographical analysis can help the modern viewer to appreciate religious paintings, a knowledge of the contemporaneous society would certainly improve the understanding of these satirical figures. Certainly caricatures that rely on universal crudeness would easily be understood without this sort of contextual information, but the drawings in this exhibition do not fall into that category. Even without such additional information, however, the most uninformed observer can note the apparent anonymity of the characters in the two series of drawings.

There is something vulnerable about a person who is seen from behind, and in Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s series, both the artist and the viewer are engaging in the impolite behavior of laughing behind someone’s back. While in real life, a figure seen from behind can be walked around and greeted face to face, in these drawings the back is the only dimension of this character that the viewer will ever meet. The artist exaggerated some of their features, posture and costume, and the very fact that they are seen from the back, having turned to the viewer the very body part that is most often the target of jokes, makes them clear figures of jest.

Caricature of a Man Holding a Tricorne, Seen from Behind

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

1760 (?)

Pen and black ink, gray wash

7 3/4 x 4 13/16 in. (19.7 x 12.2 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection

Caricature of a Man Wearing a Wig and a Tricorne, Seen from Behind

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo

1760 (?)

Pen and black ink, gray wash

7 5/16 x 4 1/2 in. (18.5 x 11.5 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection

The anonymity of being seen from behind is somewhat similar to the anonymity that Punchinello enjoys in Giovanni Domenico’s series, for these characters always appear in a mask. Even as a baby, in Giovanni Domenico’s The Infant Punchinello in Bed with His Parents, Punchinello is masked. The Punchinello drawings also include mysterious unmasked observers who appear with their backs to the viewer. However, the essential difference remains: someone in a mask can maintain his anonymity while observing his surroundings through the eye slits. In this way, anonymity of an individual seen from behind is very different from that of a person in a mask. The first one can’t see you laughing at him, while the second is not only well aware of the actions of those around him, but can also be a threatening presence that is hiding under a mask.

The Infant Punchinello in Bed with His Parents

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo

Late 18th–early 19th century

Pen and brown ink, two shades of brown wash, over black chalk

13 13/16 x 18 3/8 in. (35.1 x 46.7 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo

Late 18th–early 19th century

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over black chalk

13 3/4 x 18 5/16 in. (35 x 46.5 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection

Ultimately, the intimate size of this exhibition is the perfect setting for what will be, for many visitors, their first introduction to Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s and Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo’s satirical work. The exhibition Tiepolo Caricatures from the Robert Lehman Collection will be on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through September 28, 2014.

— Jenya Frid

Curatorial Intern