Failures.

Failures.

Attempts. Failures.

…

Failures. Not total failures (a certain embryo…perhaps for later.)

I give up.

Found at the beginning of Drawing Papers 14: Henri Michaux: Emergences/Resurgences, these lines succinctly summarize the creative process for poet and artist Henri Michaux (1899-1984). Emergences/Resurgences provides a series of beautiful and inspiring ruminations on the subject of failure in an art practice. As seen here, Michaux views failure not only as productive (towards a “victory”), but also as a source of unending questioning; failure as the conviction in one’s ideas, failure as a means of its own without the hope for eventual success. Michaux eloquently offers alternative mentalities towards failure in the studio by demonstrating the potential in the failed “embryo” of his efforts.

Written towards the end of the poet-artist’s life, as his contribution to the series “Les Sentiers de la création” in 1972 (Editions d’art Albert Skira, Geneva), the text is part of a set of publications acting as “sites” of meditation for artists to dwell on their creative “paths,” which feature the integration and engagement of their visual material and writing. Published for the first time in English to accompany the major solo exhibition, Untitled Passages by Henri Michaux (2000), Emergences/Resurgences, like many of The Drawing Center’s publications, is an object in its own right, with lasting relevance to artists, writers, and readers today. The synthesis of text and art in Michaux’s contribution to Sentiers resonates profoundly as equal parts soliloquy, poetry, confession, and treatise.

Often associated with Surrealist thought and art—indeed, my first introduction to Michaux’s work was in the Morgan Library’s Drawing Surrealism exhibition last year—the relationship of Michaux’s work to the movement is actually more complicated. He presents a counterpoint to the movement, rejecting Andre Breton’s claim to a truly automatic, unconscious drawing and writing, but within the pages of Emergences/Resurgences, the poet does state, “If I am set on taking the way of lines rather than of words, it’s in order to enter into relation with what is most precious to me, most true, most withdrawn, most “mine”…” (12), thus personifying the surrealist ideal. However, it is better still to think of Henri Michaux in conversation with Victor Hugo and William Blake: those poet-artists whose nomadic practice and hybridization of text and visual work remain outside category or epoch.

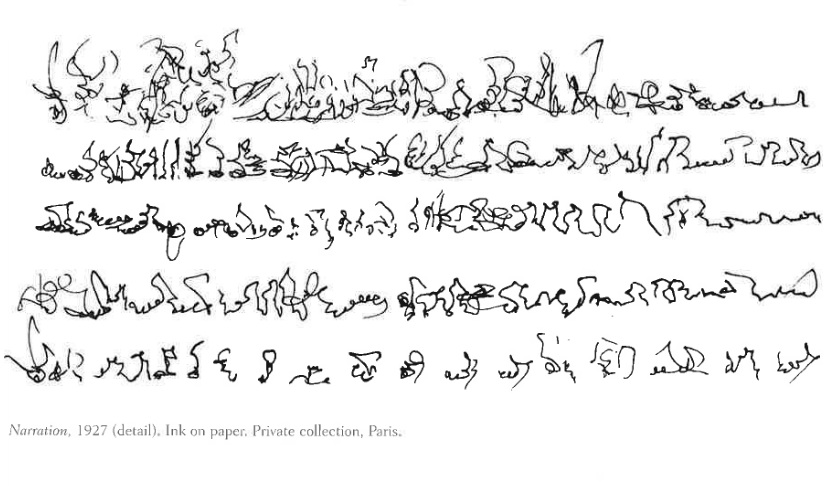

Along with solidifying Michaux’s stance on surrealism, Emergence/Resurgence delves into the artist’s initial foray into the plastic arts. In his musings on the impetus to draw, Michaux is clear: “…written things are never impoverished or rustic enough,” (12). It is in painting that Michaux is able to rediscover the primal and primitive gestures, unencumbered by the weight of language’s nuances, metaphors, and inflections. His lack of technical training makes his drawing practice particularly freeing and spontaneous. At the age of twenty-six, already an accomplished poet, Michaux took to drawing his first series, including “Narration,” (1927) comprised of “pictographic trajectories.” These trajectories refuse to follow straight translation; instead they opt to lead the viewer to certain evocations while remaining indecipherable; pictographs with no Rosetta stone. Yet, out of the calligraphic abstraction, discernible forms do merge on the page.

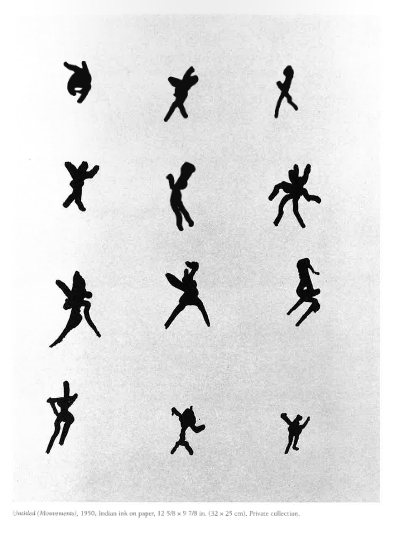

Drawn lines evoke writing; the lush opening of Narration gradually gives way to signals increasingly dispersed, as a tale petering out as the choice of words—signs—becomes increasingly difficult or uncertain to assemble. Michaux also writes of an influential trip to China that fostered in him a deep admiration for the work of the literati painter-poets of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), for the “[lines] flung into the air, veering this way and that as if seized by the momentum of sudden inspiration, and not traced out in laborious, prosaic, exhaustive, bureaucratic fashion…” (12). The formal and mental foundations of the later Mouvements series found on subsequent pages (35-38)—whole compositions featuring manipulated figure-signals—show evident references to the literati painting style.

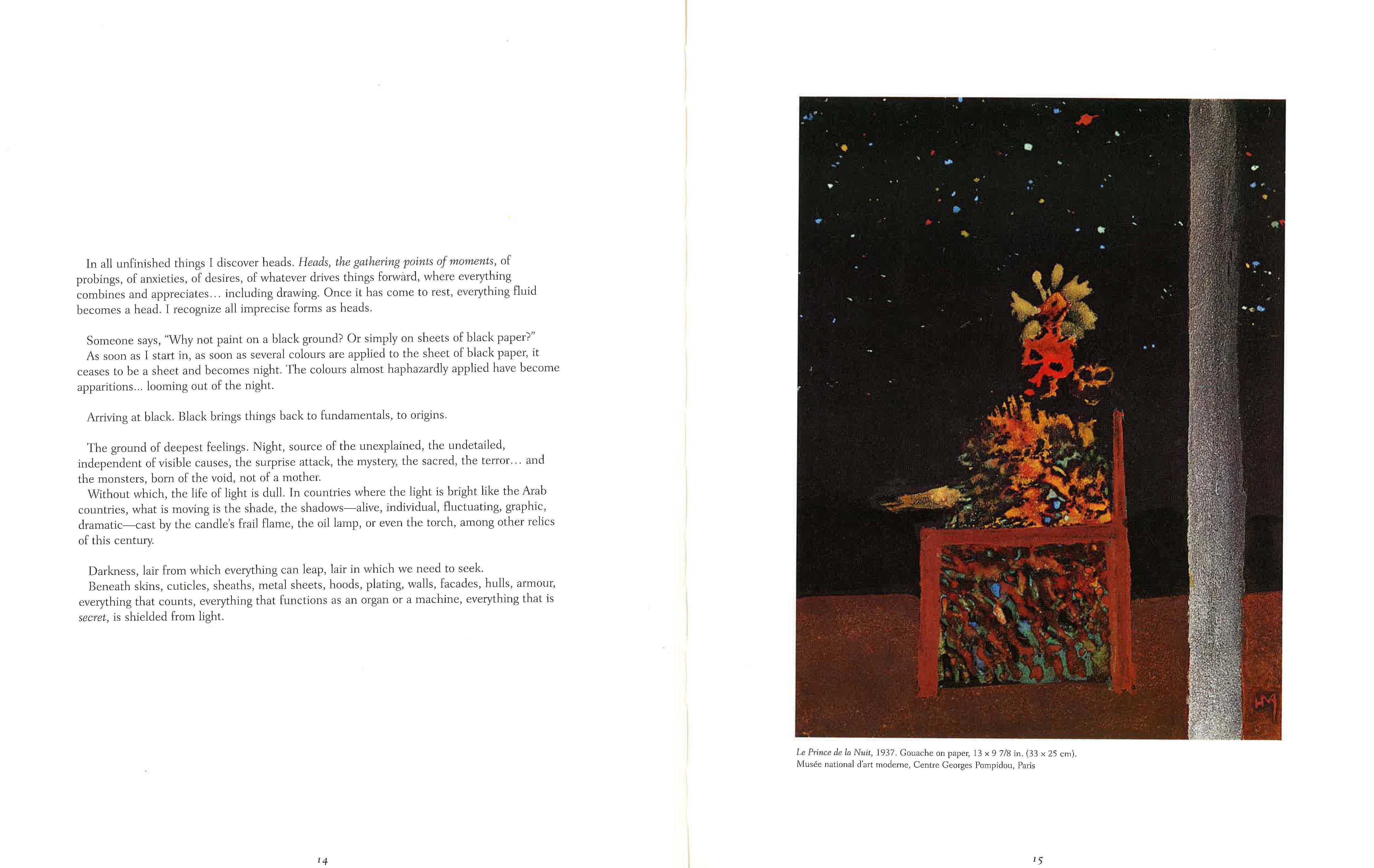

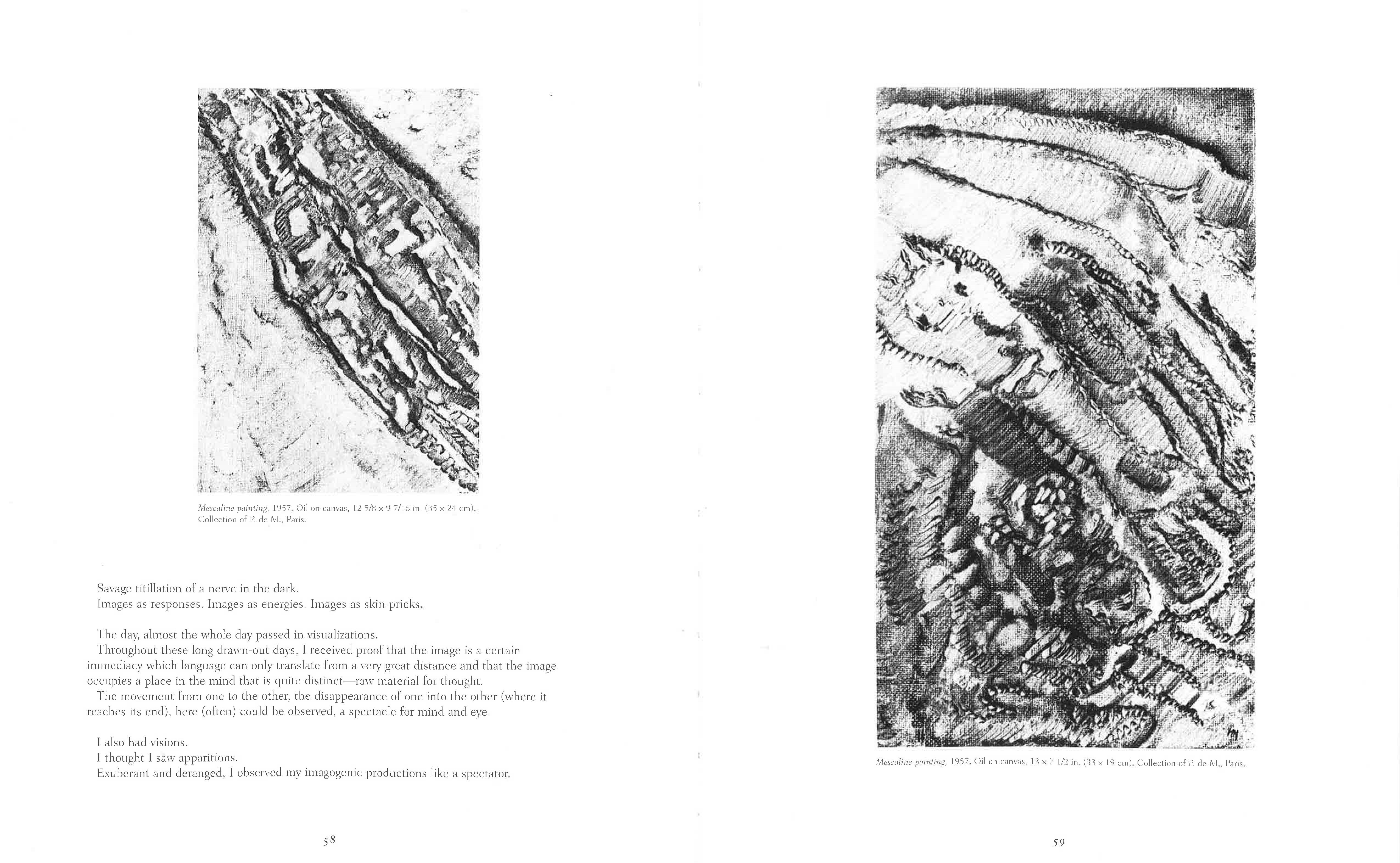

Despite his enthusiasm for drawing, Michaux never ceased to write; in fact, “The wellsprings of writing have not dried up, they recall themselves to me,” (11) and Emergences/Resurgences whirls in the hypnotizing song of the poet’s words and wisdom. Resting next to a large reproduction of Le Prince de la Nuit, 1937, is the revelation: “Beneath skins, cuticles, sheaths, metal sheets, hoods, plating, walls, facades, hulls, armour, everything that counts, everything that functions as an organ or a machine, everything that is secret, is shielded from light” (14). Within the section dedicated to Michaux’s experimentation with mescaline, and nestled textually between two works containing a frenetic confluence of lines that seem to embody the cellular—nuclei running in streams along rivers or veins in oscillating patterns of chaos and symmetry—are the enigmatic, succulent words: “Images as responses. Images as energies. Images as skin-pricks” (58). As these words imbue the reader with a psychedelic spirit, Emergences/Resurgences demonstrates the interconnectivity of Michaux’s art and writing as they relate to each other as more than mere illustration or explanatory note. The dyadic work reflects what Xie He, a 5th century Chinese writer, historian, and critic, calls “spirit resonance,” or flow of energy that illuminates text, image, and artist alike.

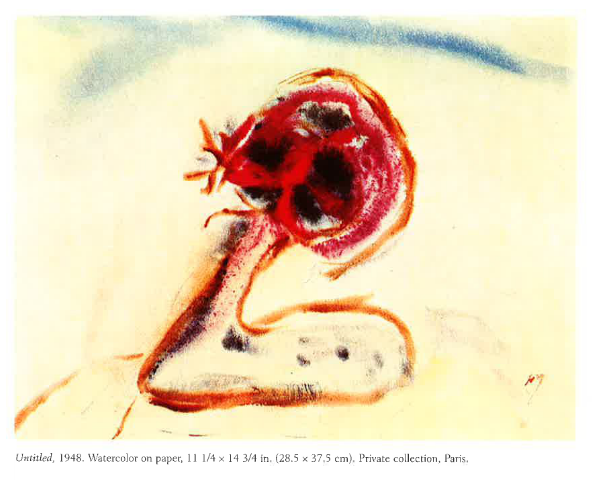

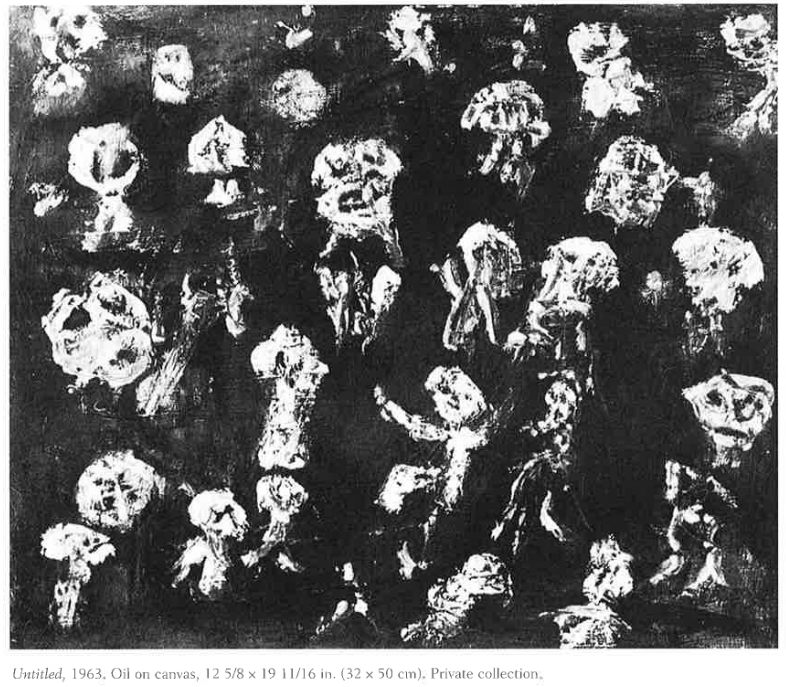

Interspersed between the articulate lessons and wandering, groovy prose, lies a subject that sprouts out of the text sporadically to reveal a more personal, vulnerable, and continual resurgence − the artist’s life. In a particularly engaging series of passages, Michaux shares the genesis of heads in his work. These objects-turned-subjects emerge unconsciously out of the watery ink and arise with much frequency during various ordeals in the artist’s life. Michaux recalls how, new to drawing, “in all unfinished things I discover heads. Heads, the gathering points of moments, of probings, of anxieties, of desires … I recognize all imprecise forms as heads,” (14). This is followed by a suite of watercolor and ink drawings revealing strange, deformed skulls and torsos done in a mixture of dry and wet ink; lines quickly vein into flesh and gesture. Later, as his wife lay dying in a hospital bed in 1948, a half-crazed and isolated Michaux wanders the wards where, “…unhappy heads, heads in extreme distress, appear on the paper, fragments of heads, desolations of being, as if they had been there all the while…” (28). These spectral forms continue to saturate his life and drawing, and ultimately Michaux embraces these unknown faces as the “truest faces” − welcome phantoms and the “realest of places.”

To read or buy the text, please visit The Drawing Center’s bookstore.

— Genevieve Wollenbecker, Bookstore Manager