Viewing Program Curator Lisa Sigal recalls a recent meeting with poet and artist Christopher Knowles.

Christopher Knowles, Red Abracadabra (detail), Undated. Typing on paper,

11 x 8 1/2 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.

I was looking back at TDC’s archives, which are organized in black binders; inside are yellowed newspaper reviews and slides from the earliest Viewing Program Selections shows, beginning in 1976. Binder number 1: Christopher Knowles, artist, 19 years old at the time, was included in the Summer Selections show, May–June 1977. Hilton Kramer’s review of the show in The New York Times questioned Knowles’s unconventional approach to drawing, a Drawing Center curatorial mandate since the founding of the museum that same year.

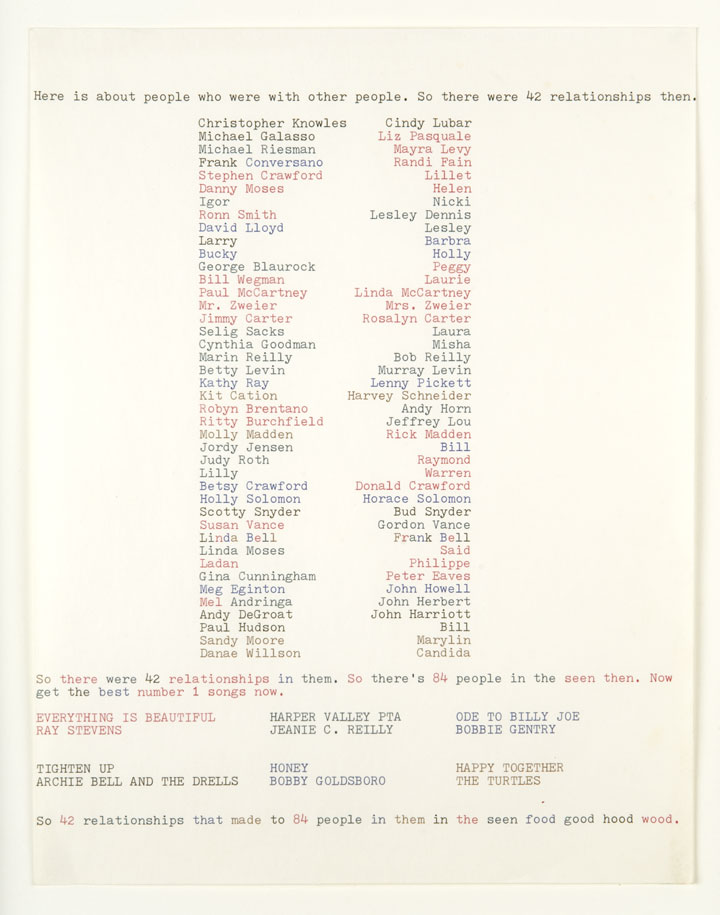

The pieces that were exhibited in 1977 were made on rolls of Xerox paper, 10 and 12 feet long, and covered with marks and patterns made with an old-fashioned typewriter. The pages are covered with repeating patterns of letters, some of which are readable, others coded. Knowles’s text drawings map time, music lyrics, song titles, movie scripts word-for-word, interior and urban space. The images shown in The Drawing Center’s exhibition were so tall that viewers were given binoculars to see the uppermost tiny text patterns. I was intrigued.

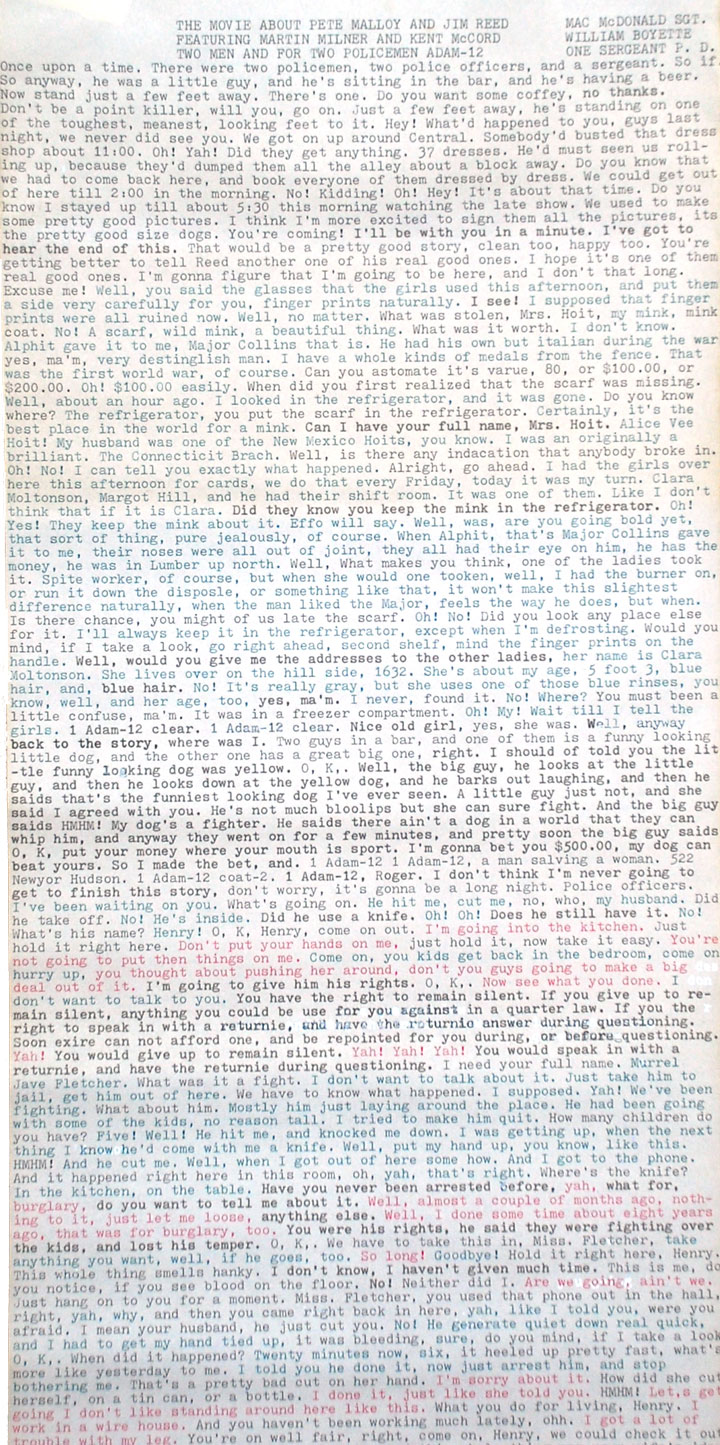

Christopher Knowles, The Movie About Pete Malloy and Jim Reed Featuring Martin Milner and Kent McCord For Two Men and Two Policemen Adam-12 (detail), Undated. Typing on paper, 33 1/8 x 8 5/8 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.

I googled Knowles and contacted his gallery, Gavin Brown’s Enterprise. I was informed that Christopher Knowles does not use computers. The only way to arrange a meeting was through the gallery. Bridget Donahue, who works at Gavin Brown, has a special appreciation for Knowles and his work and she put me in touch with him.

I was immediately charmed by Chris. As we pulled out some drawings, Chris lit up. He enjoys looking at his own work, which brings back detailed memories of his childhood home and his parents’ office. We were looking at stacks of his text work from the 70s, around the time of his inclusion in The Drawing Center show.

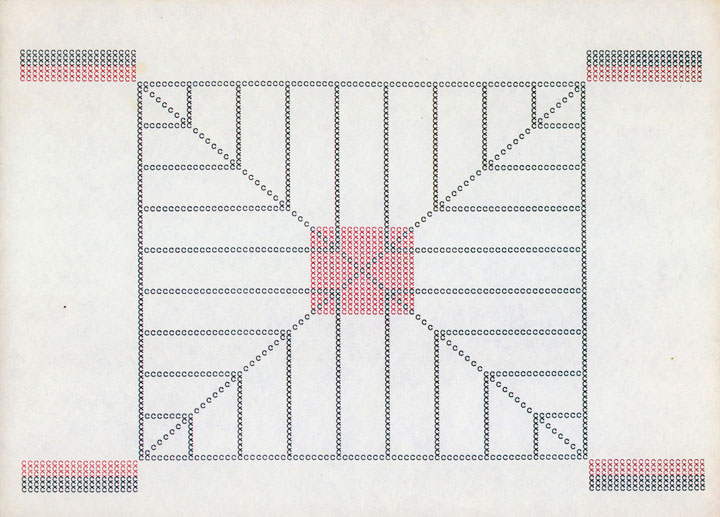

Each typewriter piece we looked at had a code to unravel, some more concealed than others. A diagram formed by patterns of c’s seemed at first to be an abstract geometric design, but turned out to be a depiction of the skylight in the loft where Chris grew up. Another work, 77WABC, May 10th, lists the names of all the station’s radio shows, their DJs, and a schedule of air times. The drawing is partly a homage to the last day the station played oldies before switching to talk radio. Its matter-of-factness combined with attention to detail fluctuates between the concrete and the poetic.

Christopher Knowles, Untitled, Undated. Typing on paper, 8 1/2 x 12 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.

Bscope is a piece that reproduces the sound of a radiator as steam and water pass through the pipes. The repetitive typed variations of Bscope feel rhythmic. The piece is rich with associations of musical sounds that are produced by commonplace objects that surround us but largely go unnoticed.

The limitations of Christopher’s process are what make the work so powerful. Colors in his work are the classic red, green and black of typewriter ribbons. In Abracadabra, the letters of this word are sequenced as an upside-down isosceles triangle. Grammatical rules are the joke in another piece: “Throw the e out the window and add ing.”

At some point Chris cocked his head and got very close to decode a piece. It seemed to be a very short letter to an ex-girlfriend. I could not make out any of the words and it took him a while to recall the code. It was a turnover text; the letters typed were from the flip side of carved wooden blocks from his childhood. “Ybir, Puevf” is “Love, Chris.”

I find Chris’s work compelling and complicated. Besides his unique approach to making work, his relationship to the work itself is unlike other artists.’ Despite the accolades and good fortune of connections, Chris, is unpretentious. His work is an illuminating case of context and audience reception.

He appreciates his good fortune in meeting avant-garde theatre director and playwright Robert Wilson as a boy. Chris was cast in some of Wilson’s productions and his poems were part of the libretto for Einstein on the Beach, a collaboration between Wilson and Philip Glass. Chris still cherishes his friendship with Wilson.

Christopher Knowles, Untitled (42 Relationships), Undated. Typing on paper, 11 x 8 1/2 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise.

We left the gallery together to walk to the subway. On our way Chris received a phone call which he politely excused himself to take on the street corner. He had an old-fashioned flip phone with a speaker. His girlfriend, who is also an artist, was calling to find out where he had been all afternoon. He responded warmly that he had a meeting at the gallery with Lisa Sigal. She asked how the meeting went and Chris said it went well. Then she asked him “Is she going to give you a show?” Chris paused and said “hold on.” He turned to me and said, “My girlfriend wants to know if you are going to give me a show.” He had asked me the taboo question that an artist is never supposed to ask.

I laughed and told him I was planning to write about his work. He turned back to his phone without any regret and repeated my response. I heard his girlfriend on the other end laughing. She scolded him for not telling her I was standing beside him.

–Lisa Sigal, Viewing Program Curator