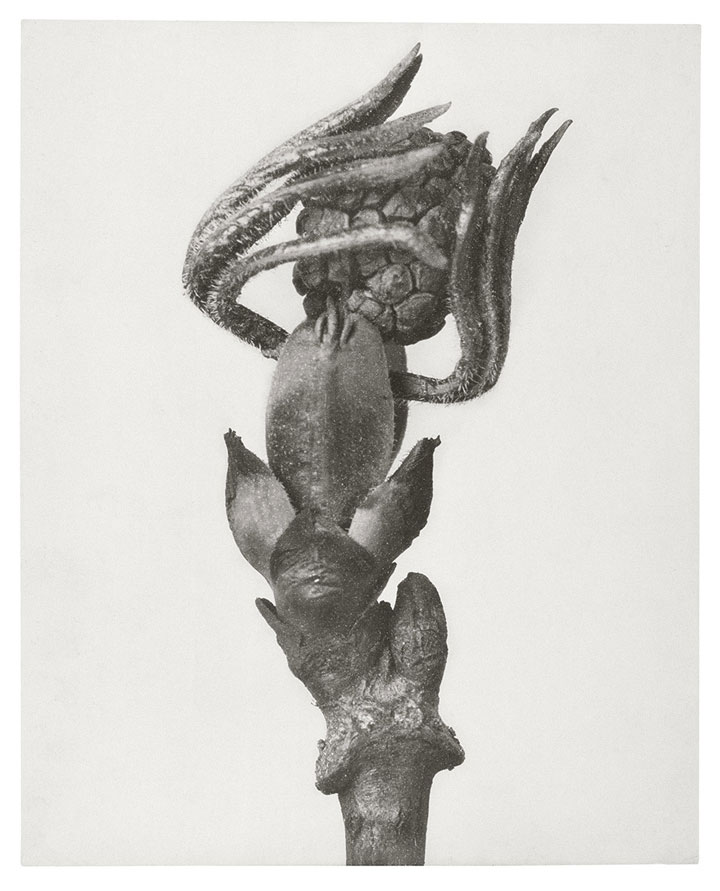

Karl Blossfeldt, Sambucus racemosa / Red Elderberry / Bud of Blossom, Undated. Gelatin silver print, 11 3/4 x 9 7/16 inches. Long-term loan from Berlin University of the Arts – Karl Blossfeldt Collection at Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne. Image courtesy of Whitechapel Gallery, London.

The exhibition Karl Blossfeldt, on view at the Whitechapel Gallery in London through June 14, brings together a wealth of material from the archives of the eponymous German artist. On display are more than eighty gelatine silver prints dated from 1900 to 1926, working collages for Blossfeldt’s famous photo-book Urformen der Kunst (1929), and ample documentation of its reception among avant-garde circles. The exhibition sheds light on Blossfeldt’s central role in reshaping the conditions of optical perception at a moment when the boundaries between unconscious, embodied, and mechanical vision were being fundamentally redrawn.

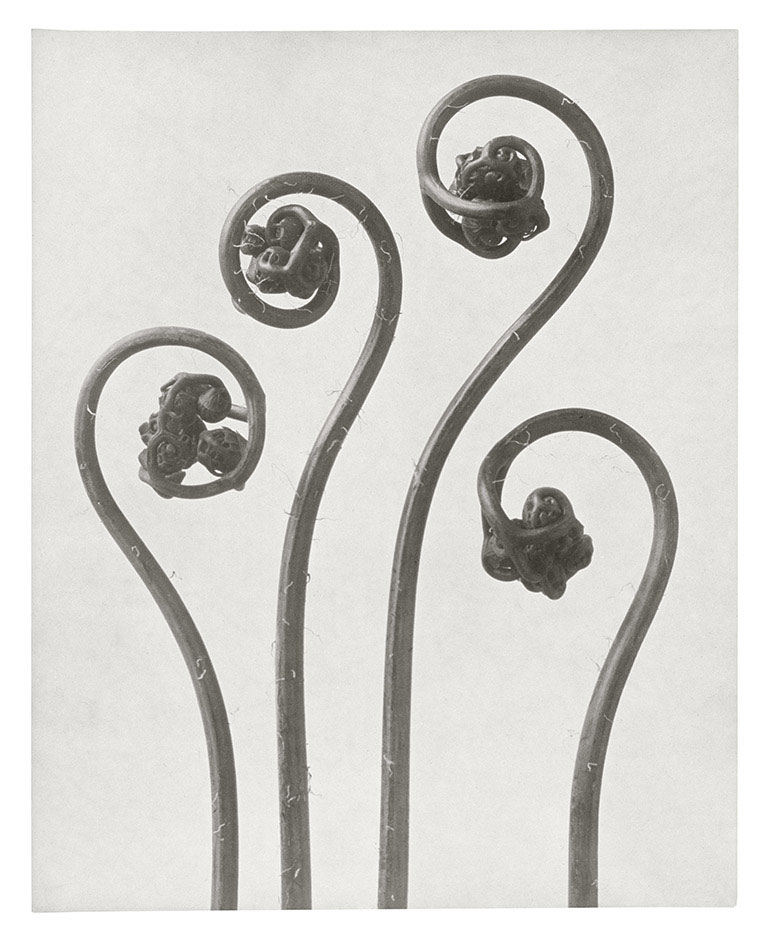

A sculptor, photographer, and teacher, Karl Blossfeldt has come down in history for his extreme close-ups of botanical specimens. In the early decades of the twentieth century, Blossfeldt devised a technique to magnify photographic details up to thirty times with the aid of a microscope. Initially, he had intended these floral enlargements for the classroom, as blueprints for biomorphic sculptural and architectural design. When he published them in the book Urformen der Kunst (1929), his name became an international bestseller almost overnight. Blossfeldt introduced the audience to a completely new and visceral order of vision. Hence, in his essay “Short History of Photography” (1931), Walter Benjamin used Blossfeldt’s close-ups to illustrate his idea of the “optical unconscious” opened up by photography and film.

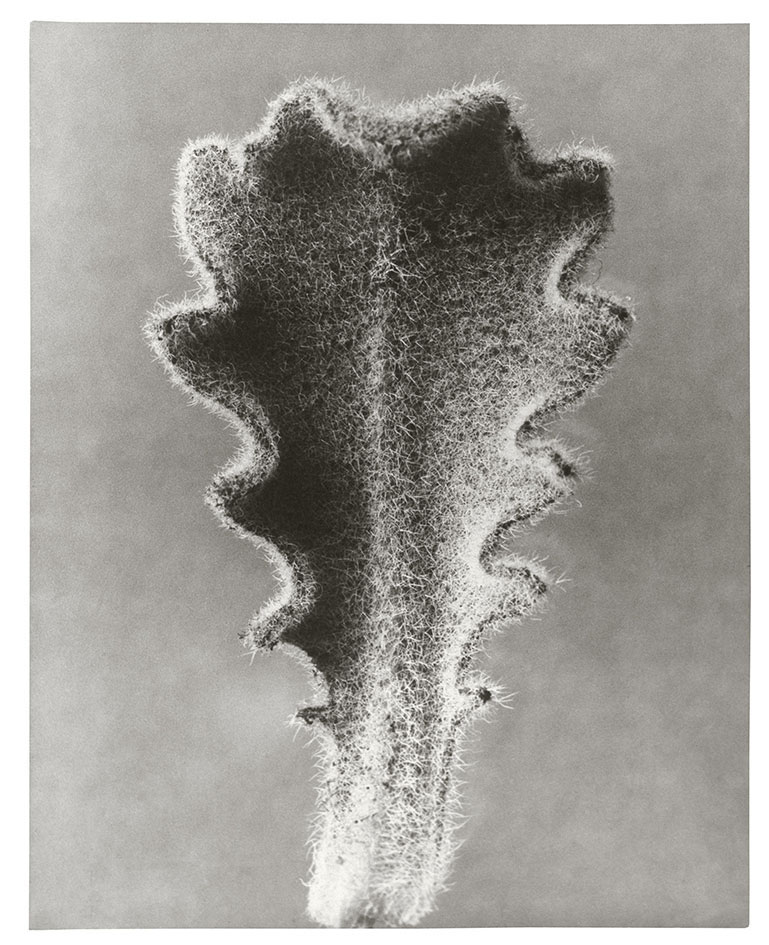

Karl Blossfeldt, Hypochaeris radicata / Hairy Catsear / Young Leaf , Undated. Gelatin silver print, 11 7/8 x 10 3/16 inches. Long term loan from Berlin University of the Arts, Archive – Collection Karl Blossfeldt at Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne. Image courtesy of Whitechapel Gallery, London.

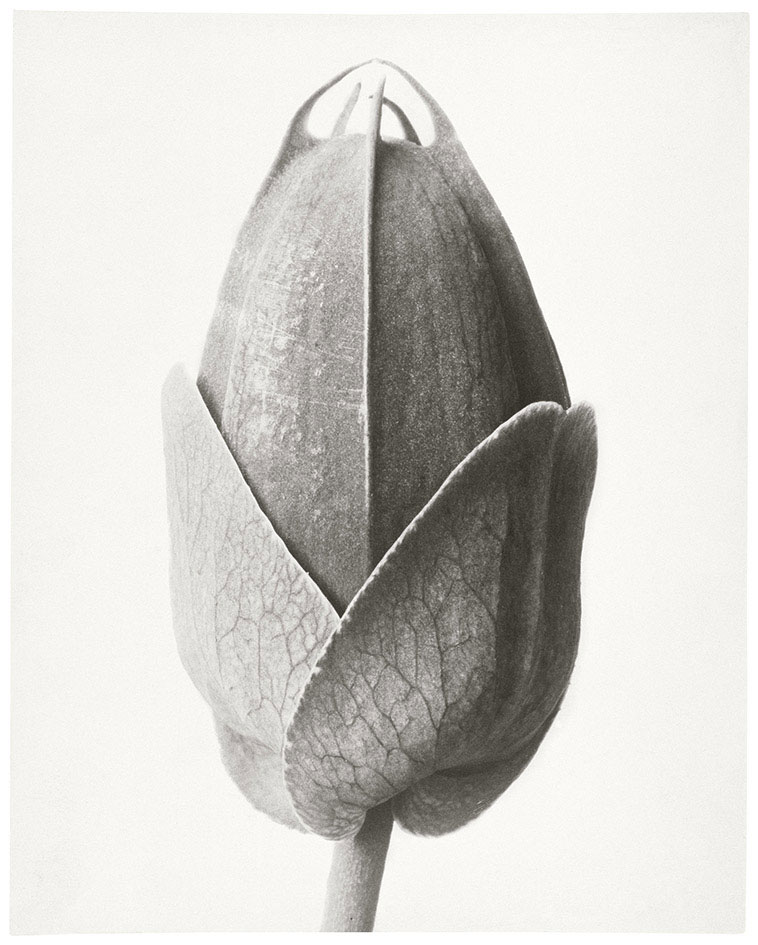

What immediately strikes the viewer upon entering the Whitechapel Gallery is that Blossfeldt’s photographs reproduce the anatomy of plants and flowers so graphically that, paradoxically, the works’ veneer of objectivity gets lost in the excess of detail. As one moves from one close-up of an artichoke to another, the status of these specimens starts to oscillate between animist totems, anthropomorphic assemblages, and carnal organs. In the process, the medium looses definition too. Blown-up foliage turns into the stone of gothic architecture. The fluffy texture of a celery stick rendered in black and white gives the illusion of frottage. It is not surprising that after seeing Blossfeldt’s prints in 1927, the art critic Franz Roh compared them to Max Ernst’s Surrealist rubbings.

It was in the context of French Surrealism that these photographs were most emphatically embraced for their uncanny eroticism. In the exhibition, a copy of Bataille’s essay “The Language of Flowers” bears witness to this history. Originally published inside Documents I (1929) with illustrations by Blossfeldt, the essay deconstructed the meaning of flowers as at once ideal symbols of love and sordid earthly shoots.

Karl Blossfeldt, Passiflora / Passion Flower / Bud, Undated. Gelatin silver print 11 13/16 x 9 7/16 inches. Long-term loan from Berlin University of the Arts – Karl Blossfeldt Collection at Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne. Image courtesy of Whitechapel Gallery, London.

The graphic quality of Blossfeldt’s photographs holds together Surrealism’s erotic imaginary and the extreme realism of Neue Sachlichkeit photography—from Albert Renger-Pazsch’s straight photographs of nature and industry to August Sander’s portraits of each and every German profession in the photo-book Faces of Our Time (1929). If some of the blossoms on display resemble uncanny anatomical drawings, their taxonomic organization also aligns them with Sander’s social typologies. The significance of Blossfeldt’s oeuvre lies in the tension between these different modes of vision—one embodied and striving for the irrational, the other mechanically precise. Benjamin captured something of it when he wrote that Blossfeldt’s prints stood at the junction of magic and technology.

Karl Blossfeldt, Adiantum pedatum / Northern Maidenhair Fern /Young Rolled-up Fronds, Undated. Gelatin silver print, 11 3/4 x 9 3/8 inches. Long-term loan from Berlin University of the Arts – Karl Blossfeldt Collection at Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur, Cologne. Image courtesy of Whitechapel Gallery, London.

–Giulia Smith, Guest Contributor