Guest contributor Thom Donovan interviews San Francisco-based artist Colter Jacobsen about his idiosyncratic source material and using drawing as a medium for conversation.

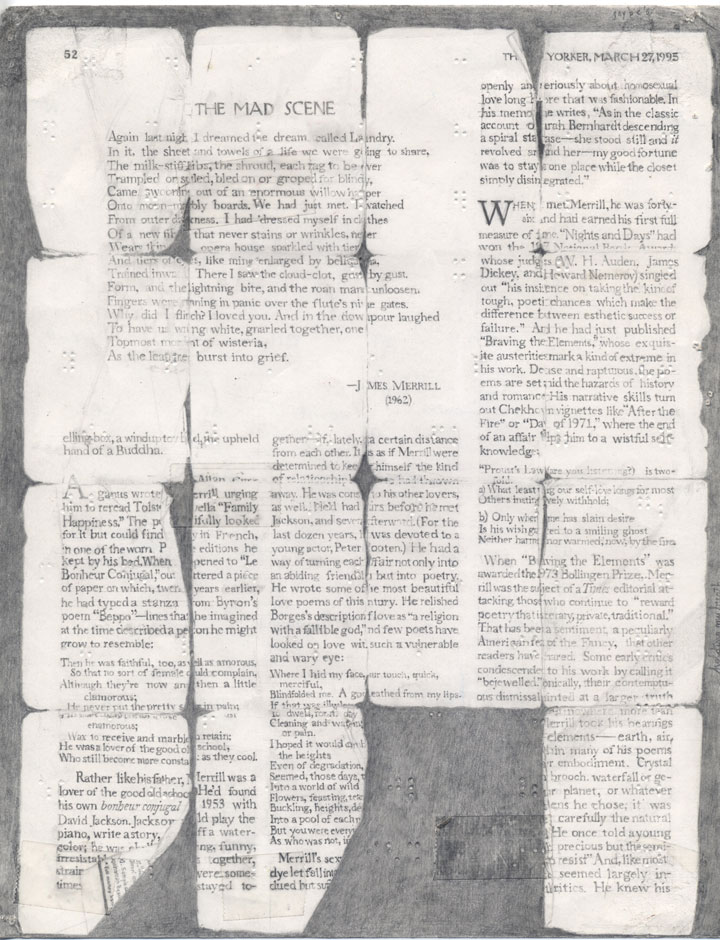

Colter Jacobsen, Holding My Breath, 2013. Graphite on found paper, 11 x 8 1/2 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

Thom Donovan: Your drawings seem to reproduce images found or sought-out in printed matter, so how do you choose what materials to draw upon?

Colter Jacobsen: It’s hard to really explain my criteria for choosing an image. It’s more like the image chooses me. Then it waits around till it needs to be manifested, and if it works, it begins to correlate with something in my present, something that I need to look at or focus on, and the drawing meets a certain piece of paper. I find that paper is very important to me as well, probably just as important as the image I’ll draw on it. Free book bins, trash cans and recycling bins, antique stores, garage sales, thrift stores, the street—these are the spots where my eyes are open a bit wider. I tend to gravitate toward discarded books (especially for their blank end pages), photo albums, old magazines, found (lost) photographs, record albums, poetry books, gifts from friends, or a casual picture my lover might send me through his phone. And then I sometimes find images on the internet. I like orphaned material, the unwanted, the discarded.

TD: Where do the source materials for your drawings come from?

CJ: Maybe I can best answer this question by explaining what I’m working on right now. I’m doing a drawing of a page that I had torn out from the New Yorker in 1995 when I was living in Baltimore. While I was working at the desk of a youth hostel there, I happened to be struck by an article about the poet James Merrill, whom I had never heard of. His life story really opened my eyes, especially his relationship with David Jackson and their using a Ouija board to write poetry. At that time, I was 18 and still in the closet, so the romantic sentiments of his poem “The Mad Scene,” printed in the article, really struck a chord with me. I folded it up and put it in my wallet and it stayed there for the next 15 years or so, snug against my right buttock.

As my taste in poetry changed over the years, so did my relationship to the poem. But it always bordered on abstraction just enough to elude me and tantalize. It had a certain kind of sorcery over me. Around the same time, there was an album by the band Lungfish, also from Baltimore, that I had been playing on repeat. One instrumental song on that album is mysteriously called “William Fuld.” I wondered who William Fuld was for a very long time. Finally, years later, while looking at knickknacks in an antique shop in my hometown, Ramona, CA, I came across an old Parker Brothers Ouija board and noticed William Fuld’s name at the top. He was the first to patent the Ouija board and eventually sold the rights to Parker Brothers. His story is pretty interesting.

TD: Do you have an archive? A research method or system?

CJ: I do have an archive of sorts, though it’s somewhat disorganized. Over the years, certain categories have emerged. I’ve got an envelope full of playing cards found on the street, envelopes of gold and silver foil from cigarettes and candy wrappers, envelopes of nearly obliterated found photos, mostly from the street. The list goes on.

My research systems tend to vary. One work I did a couple of months ago revolved around a sculpture on the University of California, Berkeley campus of one football player mending the leg of another football player. After researching this sculpture online, I went to The Bancroft Library and found an incredible archive about the sculptor, parts of which I drew from directly for the final work. An archive is so different from the internet or even a biography in book form. All the weird scribbles in the margins are nearly always left out and these are the things I find most beautiful.

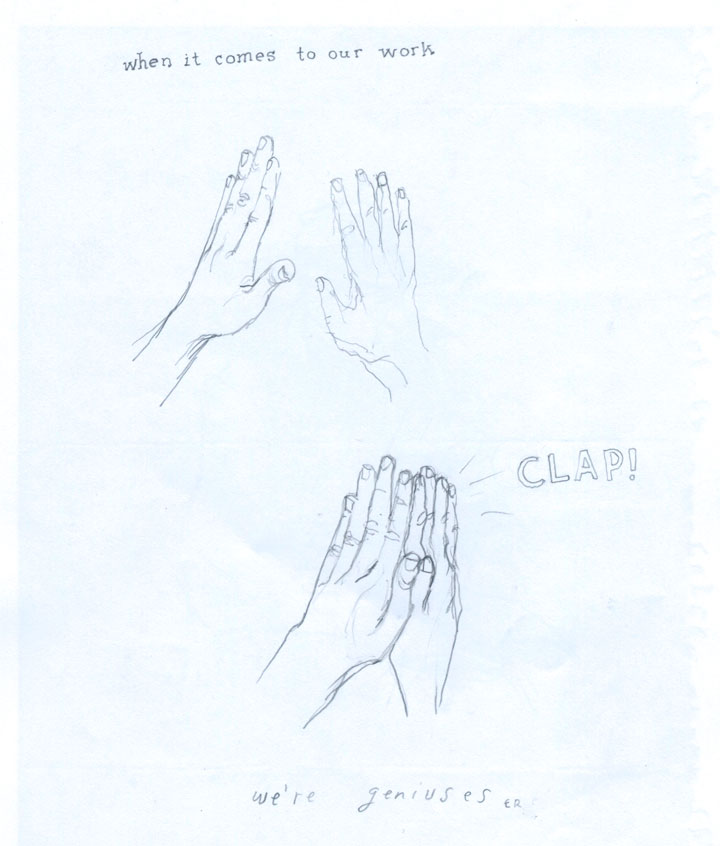

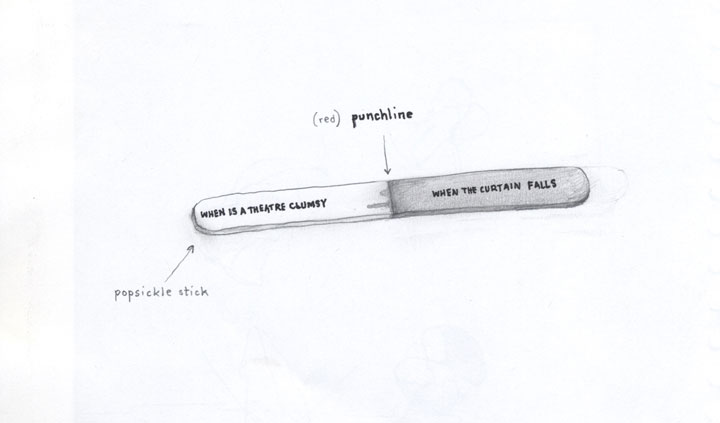

Colter Jacobsen and Matteah Baim, The Saddest Joke (excerpt), 2010. Published by Publication Studio. Image courtesy of the artist.

TD: What has your experience of collaboration been, and how does collaboration inform your work (if you feel in fact it does)? Your latest collaboration, The Saddest Joke (with Matteah Baim, published by Publication Studio) is so dynamic, like I’ve found few artists’ collaborations to be, filled with humor and incredible tenderness. I wonder if this kind of collaborative activity is typical for you and how you perceive collaboration as a moment of practice.

CJ: Most often when I collaborate, it is bouncing off of someone else’s work, as opposed to someone bouncing off a drawing I might make first. Maybe I should try that. I’d like to work on drawing hand over hand with someone. In collaborations I often feel that I am finishing someone else’s work, like in the Guy Davenport sense of finishing, as continuing to end it but at the same time polishing it. It’s like rubbing a pearl and the pearl is a story that just keeps getting more shiny.

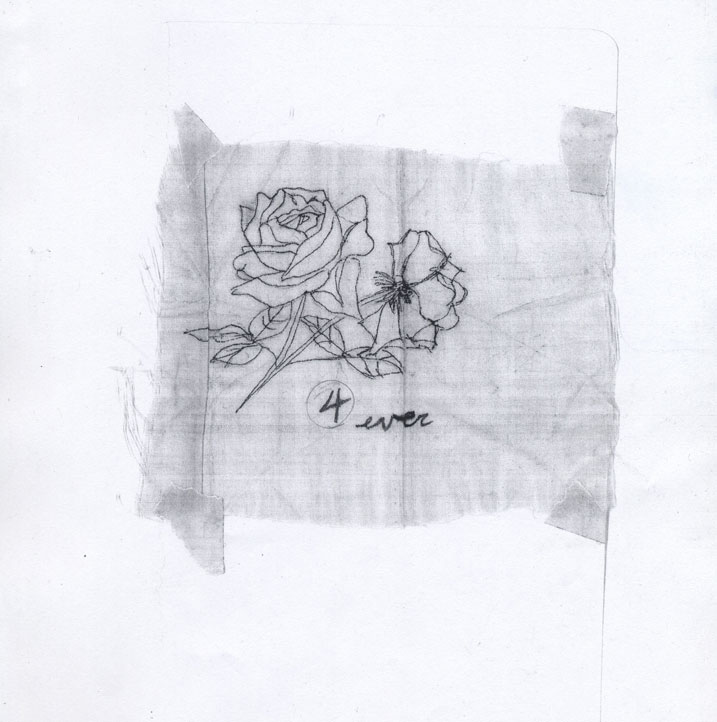

I might receive a poem from a friend and then respond to it, using it as material to play with. I made drawings from Kevin Killian’s poem “Is It All Over My Face?” which came out many years ago as a small book for the newsprint magazine Tolling Elves. I rewrote Cedar Sigo’s “’Poem for Ryan Kohl” as tattoos for the magazine Currency 4. I also did a book with Bill Berkson called Bill where he sent me a copy of a typewritten manuscript he made twenty years prior and I took two years to make drawings for each page. After I’ve worked with someone’s words like this, I’ve given their work a very close read. For me it’s the most active way of reading something.

Colter Jacobsen and Matteah Baim, The Saddest Joke (excerpt), 2010. Published by Publication Studio. Image courtesy of the artist.

With The Saddest Joke it was more effortless, more of a call-and-response or a back-and-forth. Matteah and I sent each other drawings through the mail for several years. I can’t remember how long we did this. I think the idea of it being a book started out as a joke, but then it became a real joke and then The Saddest Joke. We laughed a lot making that book. Maybe the saddest joke was the big distance of space between Matteah and me since she lives in Brooklyn and I live in San Francisco. We should live together in Kansas!

Colter Jacobsen and Matteah Baim, The Saddest Joke (excerpt), 2010. Published by Publication Studio. Image courtesy of the artist.

Like Matteah, I play music and collaborating with her feels very much like playing music. For instance, she just sent me an email about hobos. I told her that I had recently read a poem by Bernadette Mayer that says that the word hobo comes from ‘Ho! Beau!’ Matteah’s been reading up on hobo signs and symbols and whatnot and came across the term ‘California Blanket.’ So I think that’s the title of our new book. It’s as if these pieces are notes that then become chords when joined, and sometimes they vibrate and harmonize in the right way and then, whoa! Suddenly we have a song that we’re singing along to.

The Saddest Joke is available to view online here. A solo exhibition of Colter Jacobsen’s work opens at Corvi-Mora gallery in London on April 18, 2013.