Visitor Services Manager Genevieve Wollenbecker reflects on the drawings of Maria Bussmann, which were included in a 2003 group exhibition at The Drawing Center and in a recent solo exhibition at New York University’s Deutsches Haus.

Though people say we think in pictures, thought is also linked to language—so drawings are also language pictures. –Maria Bussmann

I first came across the work of Vienna-based artist and philosopher Maria Bussmann at her most recent exhibition at NYU’s Deutsches Haus, entitled Drawings Dedicated to Hannah Arendt (on view November 20, 2012–January 15, 2013). In the gallery, two suites of drawings staged an unusual confrontation between their viewers and quotidian objects. The first group, Lucy’s Toys—nearly two-dozen small pencil studies on white paper—presents baby toys that belonged to the artist’s newborn overlaid with philosophical terms. In Drawing on Hannah Arendt, the more recent group made in 2012, six pages of large, yellow presentation paper display the contents of the artist’s grandmother’s sewing kit. I found the energy of these richly detailed compositions of scattered buttons and sewing baskets mesmerizing. Though I am not a student of philosophy, this visual dynamism propelled me to investigate currents within the artist’s practice, in order to understand what the formal components of Bussmann’s work communicate to the viewer and how they address her source texts.

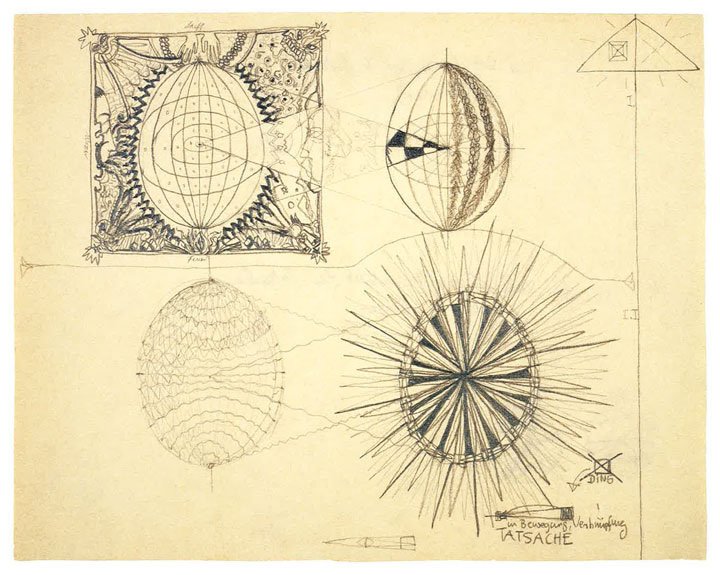

As it turns out, Maria Bussmann (b. 1966, Wurzburg, Germany) is no stranger to The Drawing Center. The museum hosted Bussmann’s North American debut in the group exhibition Mappings of Being: Selections Winter 2003. (Read Drawing Papers 41: Mappings of Being here.) The exhibition included selected works from the artist’s project Drawings to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus (1996–1999). [1] The series is an ambitious exploration of the philosopher’s seven propositions—with a healthy amount of sub-propositions—on the difference between language and reality (plus a few thoughts about science thrown in).

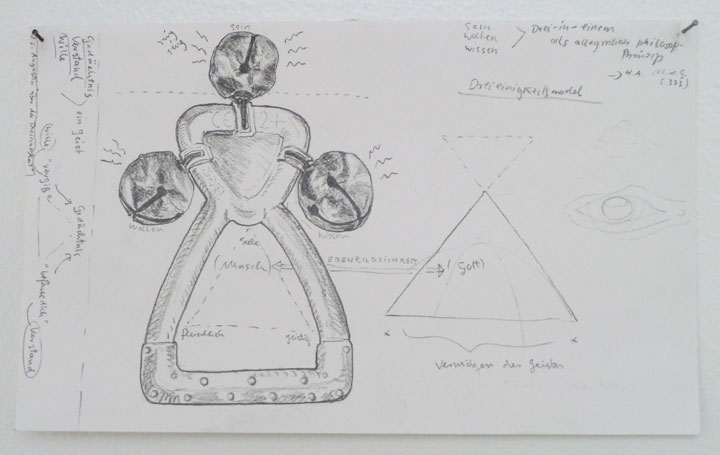

Maria Bussmann, Untitled (Proposition 1 and 1.1) from Drawing to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus series, 1996–1999. Graphite on paper, 8 ¼ x 10 5/16 inches.

In ninety-two graphite drawings on paper, each roughly the size of a notebook page, the artist builds a personal, visual lexicon of “sign-symbols” made from forms of everyday life: arrows point to and represent infinity; an egg-like circle corresponds to the world. The works are full of classical elements: friezes of figures in bacchanal poses dominate (2.04). Polygons have a large presence within certain works (a set of dark triangles appears to be marching into the distance in 2.1), and in others ellipses serve as viewing portals into other realities (1.2, 2.223). Many drawings contain flat and cursory sections alongside those that are highly resolved and skillfully rendered (2.16).

In all, the picture plane works as a grid with objects placed on coordinates and the faint lines of arrows serving as axes on a grid. At times these lines are pressed against the edge of the page, almost imperceptible; in other compositions (1 and 1.1, above) they create a large margin, revealing a void in the picture plane. The line acts as the separation between understanding and what we do not know, “what we must pass over in silence.”[2]

Throughout Tractatus, Bussmann’s forms congregate and transform into maps full of “sign-symbols” that investigate Wittgenstein’s text: the text evokes the forms. This process is inverted in the Drawing on Hannah Arendt series, where the artist chose quotidian objects with a latent symbolism evoking the domestic sphere and female presence (needles, spools, and buttons) to tease out Arendt’s “banality of evil.”[3] However, in many respects, the Arendt series can also be viewed as personal mappings of understanding, and the two series share many of the same formal hallmarks. In both the Tractatus series and the Arendt series, Bussmann doesn’t shirk the negative space of the page, but offers it the vitality of breath. Intricate compositions combine the neo-classical line work with the voodoo of a treasure map. The range of the artist’s touch—from heavy forms of saturated lines to the faintest tendrils of graphite—serves a visual feast for the lay observer. Add to that a drizzle of Bosch, and a healthy smattering of diagrams and schematic notes in German, to boot.

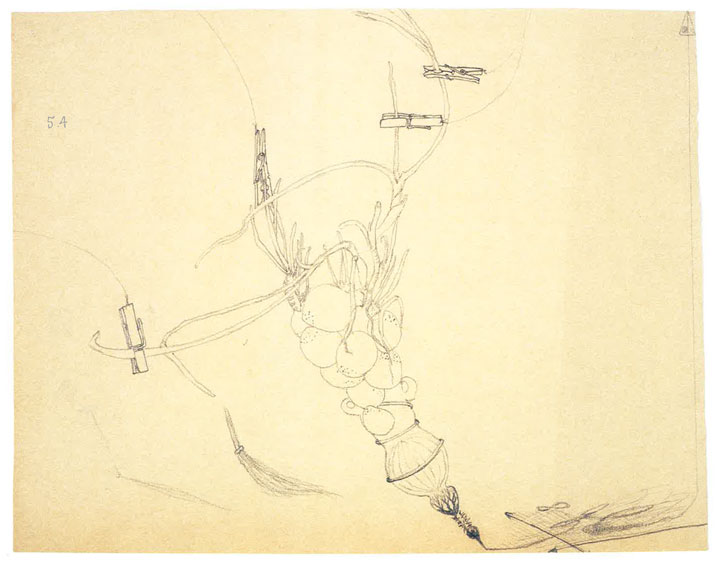

Maria Bussmann, Untitled (Proposition 5.4) from Drawing to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus series, 1996–1999. Graphite on paper, 8 ¼ x 10 5/16 inches.

Throughout both series, the artist’s humor plays on subtle and poetic chords. In Tractatus composition 5.4, a whimsical onion-and-glass fountain pen drafts infinity symbols as it swirls, top-heavy with beets whose roots are clipped with clothespins. Many of the compositions in Lucy’s Toys reveal the irony of using a toy collection to communicate philosophical vocabulary. One such index card reveals a particularly humorous stuffed caterpillar as it inches its way across a sunny landscape.

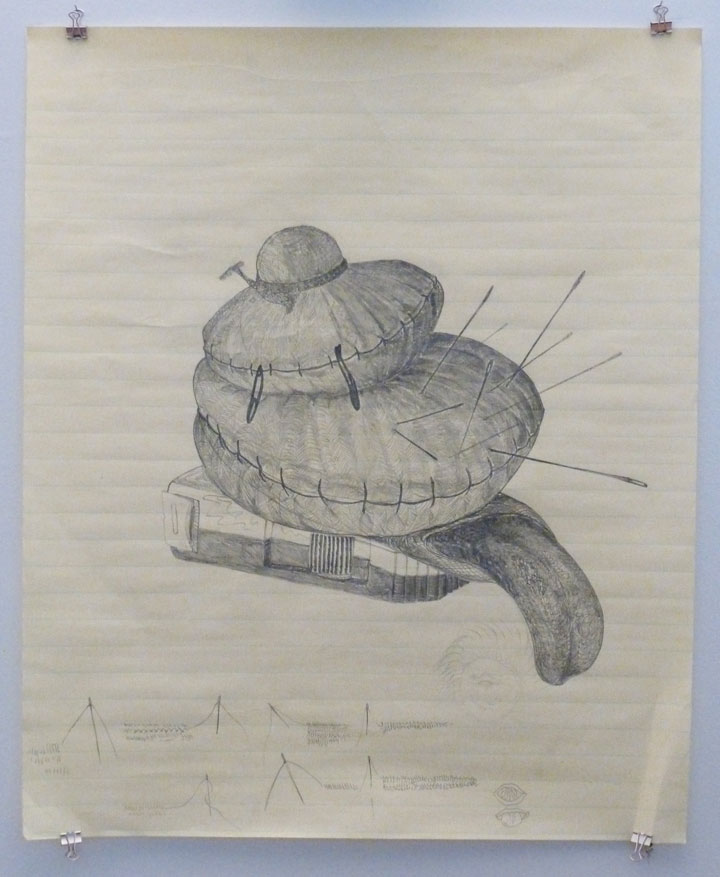

Most evident within the larger, later group of works is the kinetic energy that emanates from the detail of the rendering. A group of buttons, scattered across the large yellow page of Drawing on Hannah Arendt (Buttons), 2012, are each carefully observed and reveal their potential movement. In Drawing on Hannah Arendt (Sewing Kit), 2012, a sewing kit, comprised of bobbins, thread, and pin cushions, is composed in such a way that the viewer can revel with the artist in the rhythm found between spools of thread, or the cadence produced by the white tips of thread holders, leading the eye up and across the page of dark, heavy lines and translucent loops of string.

Maria Bussmann, Drawing on Hannah Arendt (Sewing Kit), 2012. Pencil on paper, 27 9/16 x 19 11/16 inches. Image courtesy of Hyperallergic.

In the group focused on the banality of evil, Bussmann pushes visual movement on the page to animate the subject matter. Through the magnification of the domestic sewing needle, central and poised atop an ethereal poof, the artist reflects on the potential hazard of this commonplace object. According to Bussmann, the needle refers to the sharpness of Arendt’s concept; moreover, on a visual level, the potency of the needle, a dark slice in midair, communicates danger. I wouldn’t usually think about pins in a pincushion as actively “piercing,” but in Drawing on Hannah Arendt (Pincushion), 2012, that gesture is evident. Through this metaphor and suggestion of latent, possibly menacing, energy, Bussmann conveys her ideas of Arendt’s concepts. There is a potential danger in these images that’s exciting.

Maria Bussmann, Drawing on Hannah Arendt (Pincushion), 2012. Pencil on paper, 27 9/16 x 19 11/16 inches.

–Genevieve Wollenbecker, Visitor Services Manager

[1] Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, April 26, 1889 – April 29 1951.

[2] From Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, Proposition 7: “What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.”

[3] German American political theorist Hannah Arendt, October 14, 1906 – December 4, 1975, wrote in her 1963 work Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil that the evil throughout history was not caused by fanatics or sociopaths, but by ordinary people who viewed their actions as normal.