The assemblage of more than 160 works currently on display in Drawing Surrealism at The Morgan Library and Museum serves as a fantastic primer on Surrealism through the evaluation of its techniques and mechanisms. Co-organized with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where the show was first exhibited, the New York installment features over seventy artists from fifteen countries and is an incredibly accessible international survey of the movement.

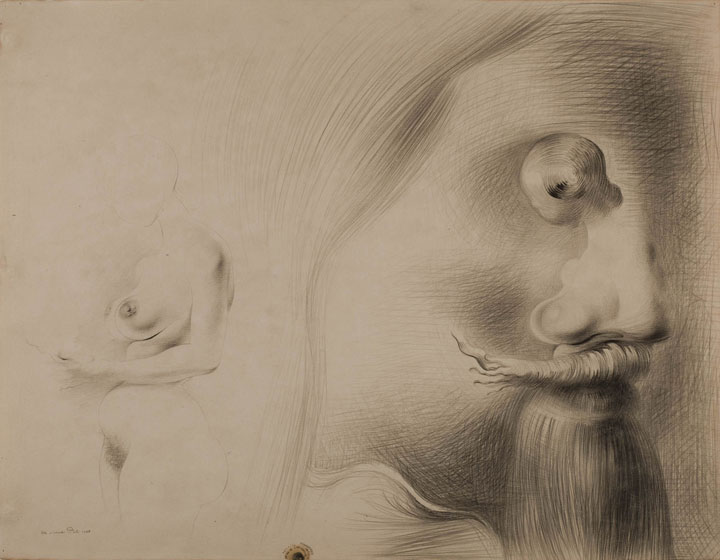

Salvador Dalí, Study for “The Image Disappears,” 1938. Pencil on paper. Private Collection. © Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2012. Photo: Michael Tropea, © 2012 Museum Associates/ LACMA.

After seeing many exhibitions focused on Surrealist paintings—à la Salvador Dalí and Yves Tanguy with their high level of finish, kaleidoscopic palette, and use of dream imagery—it was a breath of fresh air to view the concentrated bursts of raw energy found in many of the drawings at The Morgan. The show reveals the indebtedness of Surrealism to drawing and vice versa. It offers a surprisingly potent visual history that establishes the immediacy of drawing as a natural choice for artists and writers experimenting with expression of the id and the unconscious. Split between two galleries and organized by technique, the exhibition leads the viewer through a concise, fast-paced narrative of the phenomenal proliferation of drawings created by Surrealism’s champion artists and writers from 1915 through the 1950s.

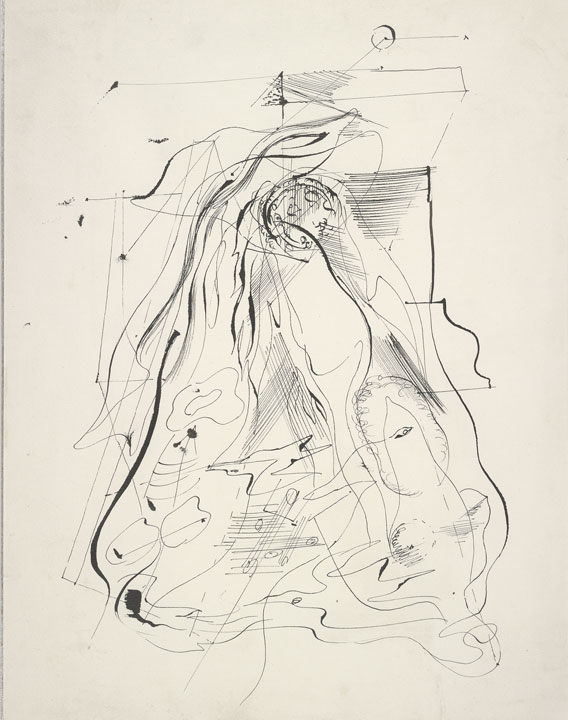

The exhibition starts with Andre Breton’s 1924 definition of surrealism as “pure psychic automatism,” and the poet’s words take form in Andre Masson’s remarkably vibrant automatic drawings. These attempts of the hand to evade the mind (with all its restrictions) show forms of mouth, breast, and genitals that dissolve into a flurry of lines. In Délire végétal (Vegetal Delirium), ca. 1925, shapes slip in and out of recognizable figuration, revealing the reality that “pure psychic automation” is hard to achieve. Masson would often go back into his drawings and rework them based on suggestions that arose, demonstrating the importance of interpretation in Surrealist works for artist and viewer alike.

André Masson, Allegories Feminines (Feminine Allegories), ca. 1925.

Private collection, courtesy of Jean-François Cazeau Gallery, Paris, France. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photo: Graham S. Haber, 2013.

The show continues to Max Ernst, a prominent figure in the exhibition, and his use of frottage, or pencil rubbings. The artist culls poetic suggestion from leaf, button, thistle, and husks and reimagines them into dreamscapes suggested from their textures. In The Start of the Chestnut Tree, 1925, a giant thistle balances a windblown chestnut-husk tree on a chalky ground. The range of lines and their saturation are so rich, the composition effortless and fresh, that one forgets the strength of Ernst’s observations is intertwined with the artist’s endeavors towards a more unconscious, mechanized technique.

Max Ernst, Le start du châtaigner (The Start of the Chestnut Tree), 1925. Frottage with graphite pencil, and gouache. Courtesy of the Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Gift of Walter Feilchenfeldt in honor of Eugene and Clare Thaw, 2011.28. © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photo: Graham S. Haber, 2012.

The first gallery also includes a glimpse into a small dissentient faction of Surrealist thought led by writer and philosopher Georges Bataille. A rare suite of drawings taken from his notebook reveal small diagrams of objects—the face chief among them—linked by a network of dotted and solid lines that appear as intense bursts of thought and process. Bataille’s dissatisfaction with Breton’s idealist leanings led to the publication of “The Big Toe,” an essay which explains that unconsciously or not, “humans possess a perverse attraction to the lowly and repulsive,” and that this is something to celebrate. What better way to illustrate the point than a large charcoal drawing by Joan Miró, Composition (1930), in which boldly delineated figure squats on the lowly appendage. The figure’s bulbous undulating outline is like a hangnail you can’t help but inspect further. Balancing this ribald celebration and resonating with Bataille’s notebook diagrams is the work of fringe Surrealist, Henri Michaux. Stemming from the poet-artist’s frustrations with the limitations of language, delicate, almost weightless, calligraphic forms in Narration (1927) flourish, composed as in a written story.

Joan Miró, Composition, 1930. Charcoal on paper. Courtesy of The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Gift of Oveta Culp Hobby. © 2012 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris.

The exhibition moves through Surrealist innovations like the exquisite corpse, a game of composite figuration, and reinterpretations of techniques like collage on an international scale, demonstrated by a large supply of arresting works by Czech and Japanese artists. Surrealists continued to push the device of spontaneity with decalcomanias, an adapted, originally decorative, form of ink transfer. Mesmerizing works by Oscar Dominquez and Georges Hugnet incorporate collage elements with deeply saturated ink patterns that are reminiscent of aquatic landscapes, part kelp forest and coral shelf. Psychoanalysis continued to inspire artists into the later parts of the movement, such as psychiatrist cum artist Grace Pailthorpe, whose Ancestors II (1935) offers uncomfortable, meaty twisting figures set down with thick frantic lines.

The latter part of the exhibition picks up speed as gradually more works challenge the movement and reveal the discontentment of many artists with Surrealism. By the 1950s, artists began to implement more strictures on the goals of their work—whether socio-political, psychological, or aesthetic—and increasingly complex compositions dominate the exhibition walls. More and more, one finds artists’ impulses toward the diagrammatic, with constellation drawings by Miró and Frida Kahlo, and visual theorems by Roberto Matta (Theory of Nature’s Strategy (Polypsychology), 1939) that further dislocate the viewer to the brink of abstraction.

While the exhibition comes to a dizzying end, Breton’s “pure psychic automatism” appears to never have been fully achieved. The attempts documented in this exhibition, however, prove well worth the effort.

–Genevieve Wollenbecker, Visitor Services Manager

Drawing Surrealism is on view at The Morgan Library and Museum, located at 225 Madison Avenue, through April 21, 2013.