On a trip to California in January I visited Viewing Program artist Dan Levenson, who recently relocated to Los Angeles from Brooklyn. We had many conversations leading up to this studio visit; the most memorable were his rants about Marx while getting lost on LA’s labyrinthine freeway system. These drives with Dan talking about freedom, labor, and art-making prepared me to appreciate his unconventional creative process.

Unlike many artists who self-impose limitations or restrictions on their work, Dan is drawn to the rules and constraints of real institutions. Dan’s multidisciplinary project Little Switzerland is built around a fictional community of artists living in Zurich in the late 90s. His work is theatrical and full of irony, exploring production in a few imaginary Swiss institutions including an art school, an art gallery, an art supply store, a publishing company, and a philanthropic tobacco company.

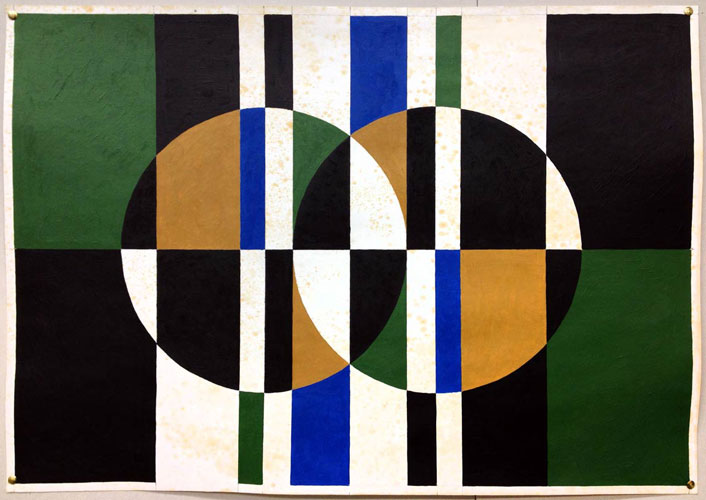

Each institution has a scripted work ethic which determines productivity. His drawings, paintings, design, publishing, and films are produced according to each institution’s protocol and serve as elaborate props or ephemera in his simulated world. Dan sidesteps authorship by removing himself from the traditional role of the artist; instead he is all the actors in his play. For instance, his delicate geometric drawings are the completed assignments of the fictional art students enrolled in the State Art Academy. Impersonating many different invented artists, Dan erases the possibility for a signature style in creating this unique body of work.

Dan Levenson, SKZ Student Painting Study (detail), 2013. Oil on aged blotter paper, 23 3/8 x 33 1/8 inches (A1 size). Image courtesy of the artist.

Dan is interested in different systems of production and how they coordinate. The dimensions of his paper follow the standard ISO paper sizes that are based on a single aspect ratio of square root of 2, or approximately 1:1.4142. The paper is treated to look worn and inscribed with number codes that correspond to the student exercises. He explained the importance of historical paper measurement to me and its connection to the metric system, which is tied to the speed of light.

His work comes alive with explanation, which makes it challenging for the unaided viewer to understand the subtext. The titles do not help: for instance, Student Painting Study. They are funny, dry puzzles. We spoke at length about presentation and how to give the viewer more clues for understanding the narrative.

Dan Levenson, SKZ Student Painting Study, 2013. Oil on aged blotter paper, 23 3/8 x 33 1/8 inches (A1 size). Image courtesy of the artist.

I asked Dan if he likes how the drawings look in the end. “What if they are not good drawings?” He responded, “The drawings will be beautiful if the art students follow the rules.”

–Lisa Sigal, Viewing Program Curator