The Prinzhorn Collection: Traces upon the Wunderblock—a show presenting over two hundred works by mentally ill patients in asylums between 1890 and 1900—opened at The Drawing Center in the spring of 2000. It would be one of the last exhibitions of this unusual body of work before it finally settled in its very own museum in Heidelberg, Germany, almost exactly eighty years after the collection was founded.

The exhibition was accompanied by one of our most extensive Drawing Papers publications to date. The book is now out of print, and there are very few copies to be found even in the hundreds of boxes of old books I’ve opened since becoming Bookstore Manager. This collection has always fascinated me, but has always remained somewhat mysterious (college art history courses don’t usually cover the art of the insane in detail). So when I came across a copy in our library, I jumped at the chance to fill in the blanks and share some of its fascinating contents, which provide valuable historical, artistic, psychoanalytic, and theoretical context for the exhibition.

Browse the complete publication online here.

Left: August Klett, Portrait of Hans Prinzhorn, 1919. Drawn on a sheet of notes left behind by Prinzhorn on a visit, 8 1/4 x 6 1/2 inches. Right: August Klett, Untitled, 1915. Pencil, watercolor, and colored pencil on writing paper, 8 3/16 x 6 1/2 inches/

The collection was amassed in the early twenties by art-historian-turned-psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn. Prinzhorn published the drawings, collages, and paintings he gathered from asylums in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland in a book called Bildnerei der Geisteskranken (Artistry of the Mentally Ill) in 1922, and had hopes to open a museum for the work as well, until his plans were delayed by the rise of fascism and the outbreak of WWII. Though they didn’t find their way into a museum until 2001, these works were wildly popular in avant-garde and intellectual circles in Europe.

In his essay “‘No Man’s Land’: On the Modernist Reception of the Art of the Insane,” Hal Foster traces the ways in which modern artists, in particular Paul Klee, Jean Dubuffet, and Max Ernst, interpreted the art of the insane, each finding their own brand of conceptual inspiration from the artworks. Where Klee saw visionary creativity and insight in an “in-between world” (page 11), Dubuffet found radical social transgression—direct expression of violence, passion, and savagery unacceptable to civilized society, and Ernst perceived a mode of disrupting identity and recreating the primal experience. However, argues Foster, while formative for modern art, these notions were simply the projections of excitable modernists seeking inspiration and affirmation on the rims of society. He asserts instead that what the art of the insane really reveals is a desired return to order. The images demonstrate the patient’s crisis of reality, and a manic urge to reestablish stability—quite the opposite of the radical rejection of social order Dubuffet dreamed of.

Sander L. Gilman’s essay “The Mad as Artists” complements Foster’s piece by tracing the historical relationship between psychiatry and psychoanalysis and the art of the insane in Europe. Prinzhorn himself did not see the patients as artists, and was concerned about the conflation—one popular at the time—of the self-conscious artist, who actively crafted an outsider status, and the mentally ill patient who (as he understood it) produced creative works as a direct result of his/her illness. For Prinzhorn, these works were diagnostically important. He hoped to derive psychiatric meaning—insights into the mental world of the schizophrenic patients—through analysis of the drawings. Yet despite his concern about the confusion of artistry and illness, he himself conflated formalism with psychoanalysis, attempting to decipher the minds of his patients from composition and subject matter. His quest to use these images in his research—to map art onto experience—betrays his own modernist fantasy: that artistic production is necessarily expressive and introspective, necessarily meaningful.

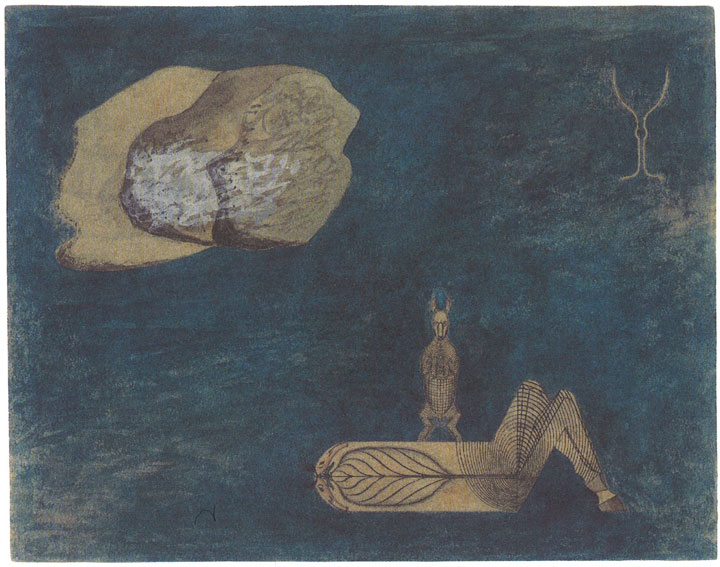

August Natterer, The World Axis with Hare (II), before 1919. Pencil and watercolor on watercolor board, varnished and mounted on grey cardboard, 9 5/8 x 7 11/16 inches.

Though artists, psychiatrists, and cultural critics of the time may not have agreed about what exactly the art of the insane had to offer contemporary culture, nor what it revealed about its makers, what is undeniably apparent is the hold these artworks—drawings, paintings, collages, and texts—had on their audience. The trials of categorization, deduction, and analysis catalogued in these essays attest to the brilliance of the actual images included in the Prinzhorn Collection. Fittingly, this installment of the Drawing Papers series is distinguished not only by the number of scholarly texts it presents, but also by the unusual quantity of color images reproduced in its pages.

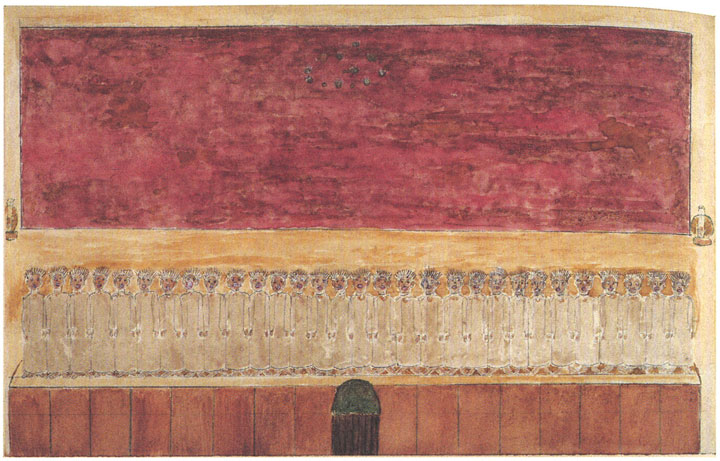

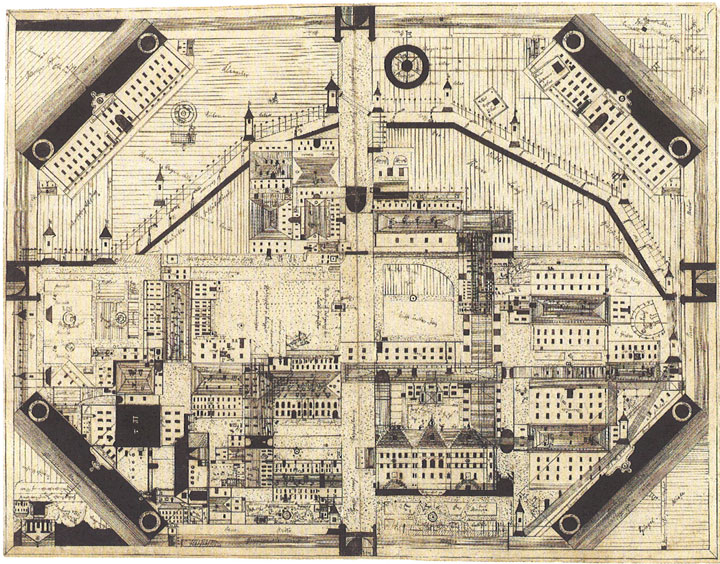

Many of the drawings are diagrammatic in composition, with texts and schema, graphs, grids, and maps. One image, for example, by Franz Joesph Kleber, a man diagnosed with “primary insanity in form of melancholia cum stupor” (page 45), shows an ornate and minutely rendered map of the institutional asylum where he lived. The image is endlessly complex: depictions of the floorplan, rooms, and buildings shown at different perspectives are layered on top of one another, creating an impression of shifting screens.

Franz Joseph Kleber, Plan of the Regensburg Institution, Kartause Prüll, 1880–96. Pen on cardboard, 18 13/16 x 24 1/4 inches.

The strong diagrammatic emphasis in some of the images seems to invite viewers to try to read or parse the complicated drawings, and thus to interpret and understand them, so it is no wonder that Prinzhorn saw them as decipherable evidence of the plagued interiority of their makers. Ultimately, however, it is impossible to unravel these images, and it is this frustration that inspires total fascination. Looking at these images is like the feeling of having something forever at the tip of your tongue. They are endlessly engrossing for they never satisfy one’s curiosity.

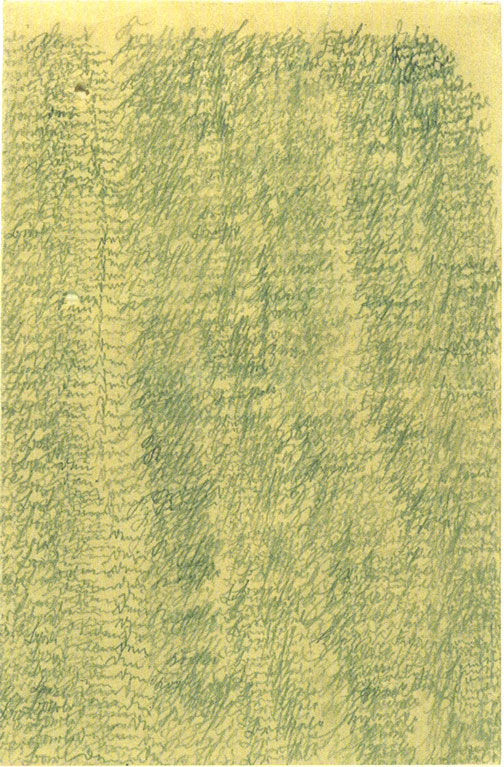

Other images in the collection are not diagrammatic at all. Many display beautifully saturated colors depict strange creatures, or stage bizarre encounters. These images also display deep pathos. Images depicting lonely figures and torn bodies, embellished with compulsive ornamentation and obsessive repetition—such as Emma Hauck’s letter to her husband in which she writes over and over “Sweetheart Come” until the page is covered in an almost indiscernible undulating line of script—remind the viewer of the physical and emotional suffering of their makers.

Emma Hauck, Sweetheart Come (Letter to Husband), 1909. Pencil on writing paper, 8 1/4 inches x 6 7/16 inches.

As manifestations of pain and loneliness—of illness, these images have an ambiguous status and challenge classification. When he first assembled this collection, Prinzhorn resisted the word for “art” (Kunst), choosing instead the word “artistry” (Bildnerei), aligning the drawings with craft. Present in all the discussions of this collection, then and now, is an anxiety about how to define art, and the consequences of such a definition for both the art and its makers. While the works of celebrated artists like Dubuffet, Klee, and Ernst are inextricably associated with their artists’ names, those of the insane efface their makers, representing the broad category of mental illness rather than individuals. And yet, despite the relative obscurity of the artist-patients, the Prinzhorn Collection helped to define and pave the way for the genre of “Outsider Art”, which is now commercially sold and widely viewed at events like the Outsider Art Fair. Thanks to the growing popularity of events like this, the public may now recognize as artists not only patients who lived a century ago, but also myriad people from a range of backgrounds whose creative activity was previously overlooked.

–Chloé Wilcox, Bookstore Manager