Genevieve Wollenbecker, Visitor Services Manager, recently spoke with artist Ishmael Randall Weeks about his past and current work, focusing on his slide project currently on view in The Drawing Center’s Lab gallery.

Genevieve Wollenbecker: Much of your work explores place, ecology, and environment. How has growing up in Cuzco, with its rich history and powerful landscape, had an effect on your practice?

Ishmael Randall Weeks: Place, narrative, and history have played significant roles in my work, but I think rather than the specificity of one location, I have tended to merge cultural, ecological, and political landscapes from the cities and countries that I have lived in and visited. Lately, however, being back in Cuzco and using it as a studio base has led me to re-assess the importance of that location. I’ve been particularly interested in revisiting the Incan archaeological sites I explored in my youth, and rereading many of my father’s colleagues’ writings about Incan culture, cosmology, and architecture. I am now looking at ways to stress the particulars in my sculptural activity by merging my interests in Latin American modernist architecture, the Andean vernacular framework, and the sociopolitical arena at hand.

GW: Your practice seems to incorporate both architectural installation and sculpture, as well as work like your project for The Drawing Center, which involves manipulating recycled photographs and slides. What is the relationship of these two aspects of your work and how did they evolve?

IRW: Much of my sculptural work has been as influenced by architecture and urbanism as by the dramatically brutal Peruvian political environment of my youth. My works on paper have been pivotal in trying to understand many of the spatial problematics that I have been dealing with in my installations. In 2006, I made a show consisting of several separate installations that attempted to deal with our use of materials within architecture by assigning new roles to those materials. I think this led me to a desire for further research, as I came to see that there were holes in my understanding of recent past events that could form an ideological narrative regarding the construction and execution of public space. In the photo-transfer pieces, I’ve chosen works from each architectural movement in the past century and transformed them into visual products, adding annotations on top which continue the dialogue initiated in my previous drawings.

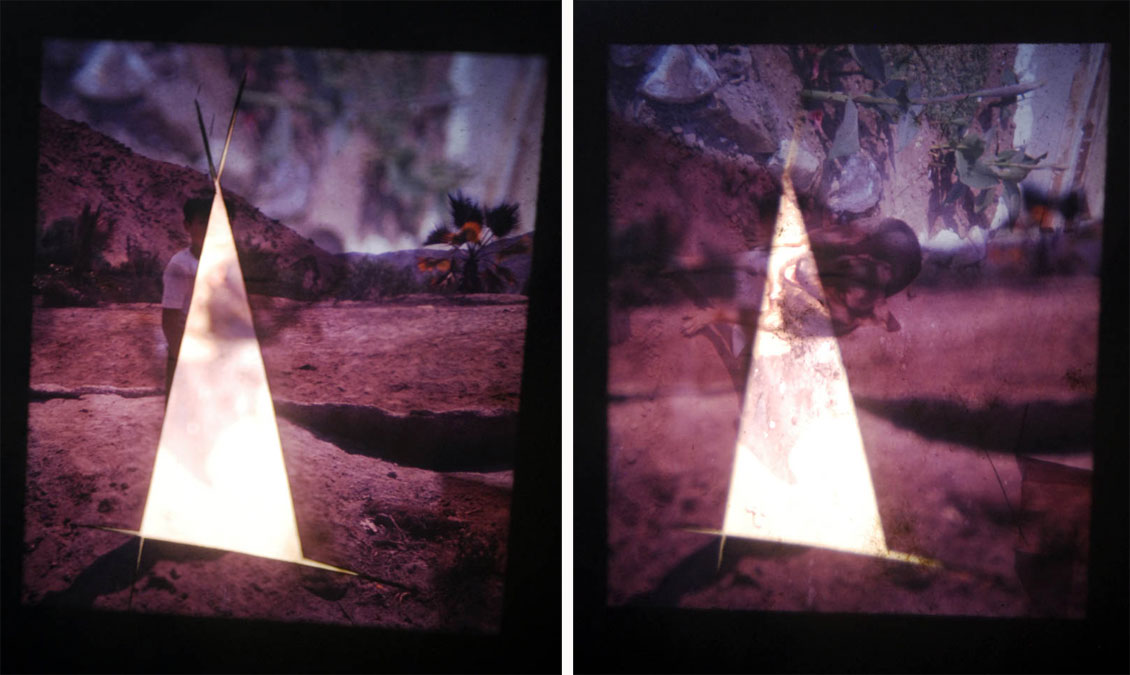

The slide project takes this research further. I started looking for information about the origins of the charged period in South America between the 1960s and 1980s, from an urbanistic and architectural viewpoint. I’ve searched archives, flea markets, and libraries for images of architecture from this dictatorial and socialist period, as well as those who were involved with and/or inhabited said structures. By cutting, burning, and puncturing these images, I feel that I have been able to convey a sort of fragility, mixed with freeing gestures that allow the past to be revisited while avoiding nostalgia.

GW: I’m glad you brought up the mark-making in this project. In these slides in particular, your manipulation of images resists the digital and embraces both visually and conceptually raw action on the part of the artist. The gestures in this project—cut, burn, puncture—have associations of violence, but it is interesting to know that they also preserve this “freeing” quality for you. What is at stake in the rough handling of these works?

IRW: Rough handling? I am not quite sure that I would consider this work to be rough. It is much more methodical, introspective, and meticulous. The slides as physical objects are quite small, and the marks, punctures, cuts made into them are relatively minimal. However, it is interesting that once they are projected and seen in a larger context with the rest of the carousel, they do have associations of violence and raw action.

GW: The slides often depict groups of figures and landscapes, and do not contain much architecture in the traditional sense of buildings and structures. Could you define your understanding of architecture in this suite of slides?

IRW: That is an interesting question—although I disagree with the suggestion that the slides do not contain much ‘traditional’ architecture. I think that my understanding of architecture has evolved into thinking about systems as a whole. I am as interested in Vernacular architecture—from the basic-needs perspective of structure (shelter, security, etcetera)—as I am in architecture’s technical, social, and environmental considerations in designing and constructing form and space.

GW: And on a formal level? You create geometric voids and obstructions that erase the subject and create a space, or structure, within the slide itself. How do these structures inform your understanding and reading of the image itself?

IRW: The carousels I am using hold 80 slides. Some are punctured, some are doubled-up, burnt, cut-into, drawn-onto, taped—and then there are many that have not been touched. To alter these images by marks through or on the surface is to study the image, to reflect on it. Sometimes I project the image a couple of times and change it again, and then again, until it feels right and has the weight and tension I am looking for. In the editing process many slides are discarded because the void takes over or because the image has no relationship to the cuts and marks. All this is circumscribed by the actual history and origins of each specific slide, which has been altered by a personal, gestural narrative.

Chloé Wilcox, Bookstore Manager, also contributed to this interview.

Ishmael Randall Weeks: Cuts, Burns, Punctures is on view in The Lab from January 17 through March 13, 2013.