On April 16th, The Drawing Center will present a listening session for Inevitable Music by the French composer Sébastien Roux. Roux’s electronic score was created by translating Sol LeWitt’s instructions for wall drawings into instructions for music. In the context of The Drawing Center’s exhibition Drawing Dialogues: Selections from the Sol LeWitt Collection, which opens April 14th, Roux’s music will highlight the link between drawing and musical notation demonstrated by a number of works on view.

This week, as Roux prepares for his performance, Curatorial Intern Allie Wilkinson takes a few moments to learn more about his process and the influence of LeWitt on his work.

Allie Wilkinson: Describe your first encounter with Sol LeWitt’s Wall Drawings. In that moment, did you know you would translate them into music?

Sébastien Roux: I first discovered Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings at Dia:Beacon in 2010. [Dia:Beacon’s] exhibition features thirteen wall drawings conceived between the late 1960s and the early 1970s. At that time, I was very interested in graphic notations (such as the first notations by Morton Feldman, Christian Wolff, Earle Brown, etc.) as well as “musical” paintings by Paul Klee, Mondrian, etc. This interest led me to develop the principle of “sonic translation.” Sonic translation consists of using an existing work (a novel, image, film…) as a score for a new sound piece. When I saw LeWitt’s wall drawings, I immediately saw graphic notations. On the train ride back to New York, I had the idea to make them audible.

What makes LeWitt’s artwork “translate” so well into music?

During one of our first conversations about LeWitt’s work, Béatrice Gross told me that LeWitt was a great music lover. He would spend his afternoons listening to music (everything from Bach to contemporary music). Moreover, he supported composers such as Steve Reich by purchasing their first scores (which, to this day, are in the LeWitt Collection). He also collaborated with Philip Glass for Dance by Lucinda Childs.

Thus, we can imagine that music influenced his work. For example, the formal structure of Bach’s The Well- Tempered Clavier, which rigorously explores all major and minor keys, is echoed in LeWitt’s Incomplete Open Cubes, in which he identifies all 122 variations of a three-dimensional cube with different sides missing. For these reasons, and many others, music is present in LeWitt’s work.

Steve Reich, First version of reductions from Drumming, 1970. Graphite on staff paper, 12 x 9 1/4 inches. © Copyright 1971 by Hendon Music, Inc. Revised, © Copyright 2011 by Hendon Music, A Boosey & Hawkes Company. International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Shown by Permission for the Exclusive use of The Drawing Center, 2016.

In your opinion, what is the link between artist and composer?

I think of what Alvin Lucier wrote: “I have often thought of LeWitt as a musician.” It’s an interesting analogy. Just as the composer writes a score that will be played by musicians, LeWitt gives a series of instructions to the draftsman who will execute his drawing.

How do you choose the sounds you use? Do you attempt to echo the form of a line with the form of the sound?

For a good number of his wall drawings, LeWitt uses simple forms and primary colors. To create a sonic analogy, I used simple electronic sounds, basic elements of electronic music vocabulary, namely: sine waves, saw tooth waves, square waves, and white noise.

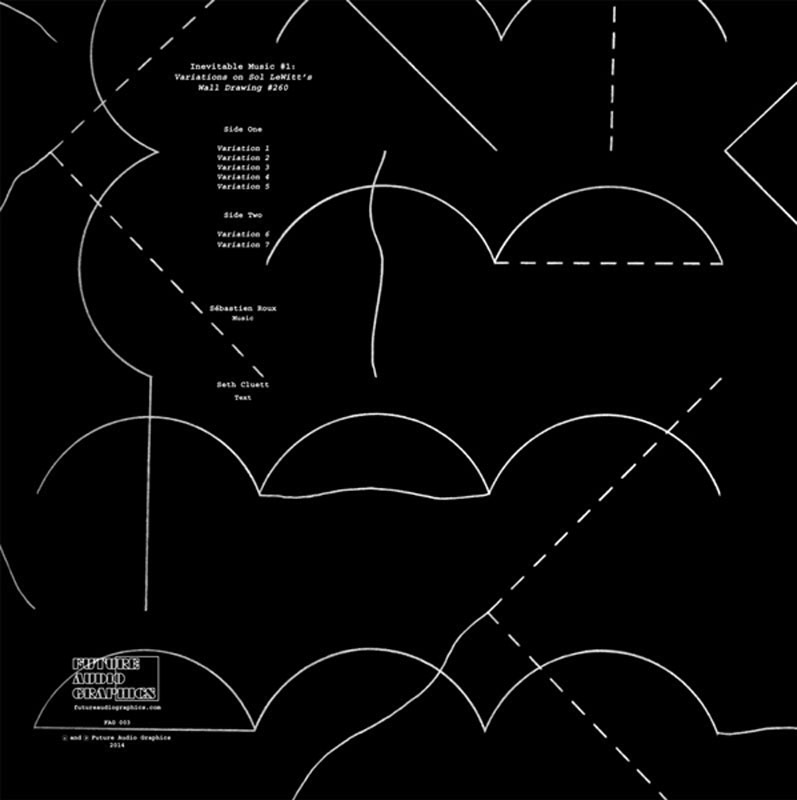

For Inevitable Music #1, a cycle of sonic translations of Wall Drawing #260, I took the analogy a little further. LeWitt gives the following instructions for executing the drawing: “All Two-Part Combinations of White Arcs from Corners and Sides, and White Straight, Not-Straight, and Broken Lines.”

The “straight lines” are continuous sounds, the “broken lines” are pulsed sounds, and the “not straight lines” are sounds with vibrato. The lines that go up are ascending sounds, the lines that go down are descending sounds, and the horizontal lines are stable sounds.

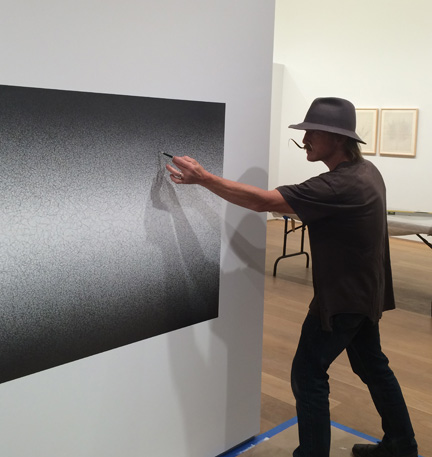

Michael Benjamin Vedder (pictured here) and Tim Wilson drawing Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #1271, Scribbles 12 at The Drawing Center for “Drawing Dialogues: Selections from the Sol LeWitt Collection,” opening April 15th.

Why did you choose to include a voice component at the beginning of each piece?

The name of a wall drawing by LeWitt corresponds to the instructions for executing the drawing. I wanted to keep this principle by presenting each sound piece with a pre-recorded voice that describes the score for the music. For example, the sonic translation of Wall Drawing #260 is “all two-part combinations of a stable sine tone, and ascending sine tone, a descending sine tone, in continuous, vibrato, and pulsed forms.”

Presenting the score affects the listener in two different ways. One the one hand, the listener might try to imagine the piece a priori and then compare that with what he or she hears. On the other hand, knowing that there is only one compositional gesture, the form of the piece given by the translation, the listener knows that there is nothing else to expect but this one score. The listener does not expect a succession of gestures or effects that will revive his or her attention. The listener can therefore fully immerse him or herself in listening to the sound, without trying to find compositional clues.

By presenting the score orally, sometimes even indicating the length of the pieces, the listeners know what to expect and can be at home with pieces that have a wide variety of run times (from 15 seconds to 15 minutes).

Finally, the intervention of the voice creates pauses for the listener, who can relax his or her “musical attention” for a few seconds.

Sol LeWitt created hundreds of wall drawings. Can you explain how you chose the wall drawings you reference in Inevitable Music?

For the listening session at the Drawing Center, I chose Wall Drawings #43, #260, and #422.

I chose these drawings for the beauty, simplicity, and quasi-mathematical rigor of their formulation, and for the admirable visual result.

As with most of the tracks of Inevitable Music, my starting point is the list of instructions given by LeWitt, rather than the drawing itself.

What interests me with Wall Drawing #43 is how the instructions, “All Two-Part Combinations of White Arcs from Corners and Sides, and White Straight, Not-Straight, and Broken Lines,” describe an ensemble rather than a drawing created sequentially: uniform dispersion, maximum density. Also, the use of simple motifs: straight lines, primary colors and black. Wall Drawings #260 and #422 are sequential; they aren’t ensembles like #43. They start with a set of simple forms and explore all the possible combinations. Then, #260 explores all the pairs, and gives rise to a uniform piece, while #422 proposes all the combinations, from the most simple (one-part) to the most complex (four part) and takes the form of an accumulation, a crescendo with an abrupt ending.

Drawing Dialogues: Selections from the Sol LeWitt Collection is curated by Claire Gilman, Senior Curator, and Béatrice Gross, Guest Curator and LeWitt scholar.

Allie Wilkinson, Curatorial Intern, is a New York-based artist, independent curator, and educator.