Widely known for his erotic and exotic art, late nineteenth-century painter, Gustav Klimt (1862–1918) was a prominent and influential figure in Viennese cultural life. Along with other founding members of the Vienna Secession, Klimt produced a magazine called Ver Sacrum—“Sacred Spring” in Latin—a platform for drawings, designs, and literature that represented this style. The movement, which included Egon Schiele and Otto Wagner, allowed artists to explore beyond the constraints of academic tradition and provided a venue for unconventional artists to exhibit and explore their craft. Klimt and the Women of Vienna’s Golden Age, 1900–1918, on view at the Neue Galerie New York until January 16th, 2017, delves into the portrayal of women during the turn of early twentieth-century in Vienna. Divided into three galleries—“Decorative Arts,” “Klimt,” and “Drawings”—the exhibition features numerous paintings, drawings, and vitrines full of jewelry and decorative objects as well as vintage photographs of Klimt.

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Szerena Lederer, 1899. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Purchase, Wolfe Fund, and Rogers and Munsey Funds, Gift of Henry Walters, and Bequests of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe and Collis P. Huntington, by exchange, 1980.

The presence of fashion and design in fin-de-siècle Vienna supplement the exhibition in the Decorative Arts Gallery. Dresses produced by Han Feng, Shanghai-based artist and designer, and influenced by the designs of Emilie Flöge (Klimt’s partner), a prominent Viennese fashion designer, are juxtaposed with vitrines full of accessories that were typically used by high society of from the 1890s to the 1910s. An armchair designed by Koloman Moser, one of the artists included in Ver Sacrum, recalls the designs and architecture innovated during the movement. These decorative objects accompany several turn-of-the-century portraits in the room, for instance Klimt’s Girl in the Foliage (1896).

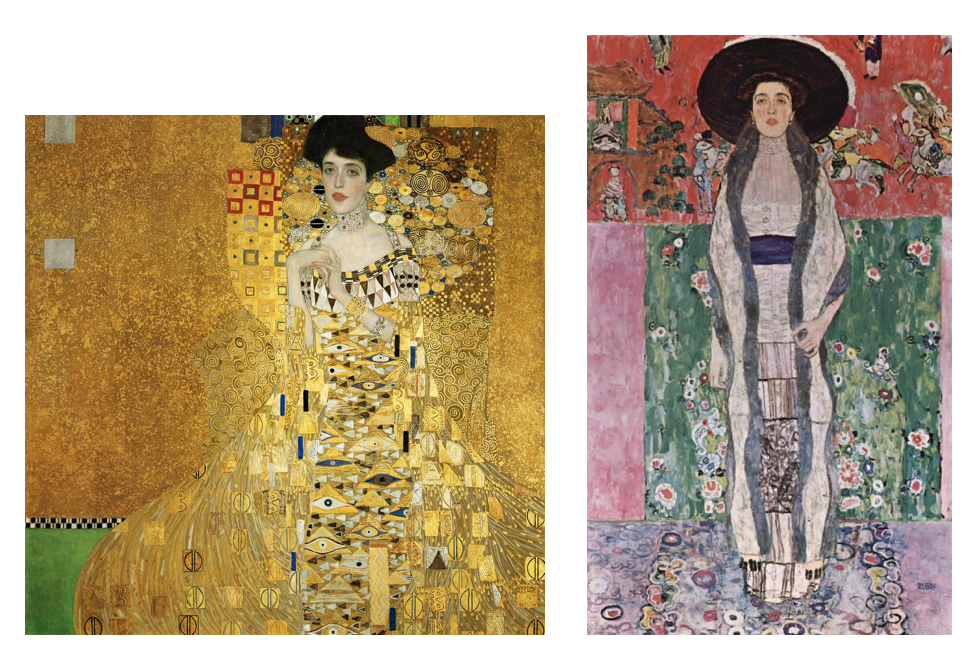

The majority of Klimt’s portraits of clients and patrons are located in the second gallery, including Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907)—also known as “The Woman in Gold”—and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II (1912), which are shown side-by-side for the first time in almost a decade. Klimt’s vibrant and vivid palette fills the gallery, and his influences from past art movements are noticeable in each of the sitters’ portraits. Moreover, stylistic changes in these portraits are more pronounced when comparing one to another: Portrait of Szerena Lederer (1899) showcases the influence of Symbolism, while Klimt’s “golden phase” seen in Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I. Klimt’s most successful “golden phase,” marked by his use of gold leaf, was inspired by a trip to Venice and Ravenna and particularly the mosaics in the Basilica of San Vitale. His portrayal of Bloch-Bauer clad in gold includes Byzantine mosaic elements as well as intricate patterns transformed from basic shapes.

LEFT: Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907. Gold, silver, and oil on canvas. Neue Galerie New York; acquired through the generosity of Ronald S. Lauder, the heirs of the Estates of Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer, and the Estée Lauder Fund. RIGHT: Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II, 1912. Oil on canvas. Private Collection.

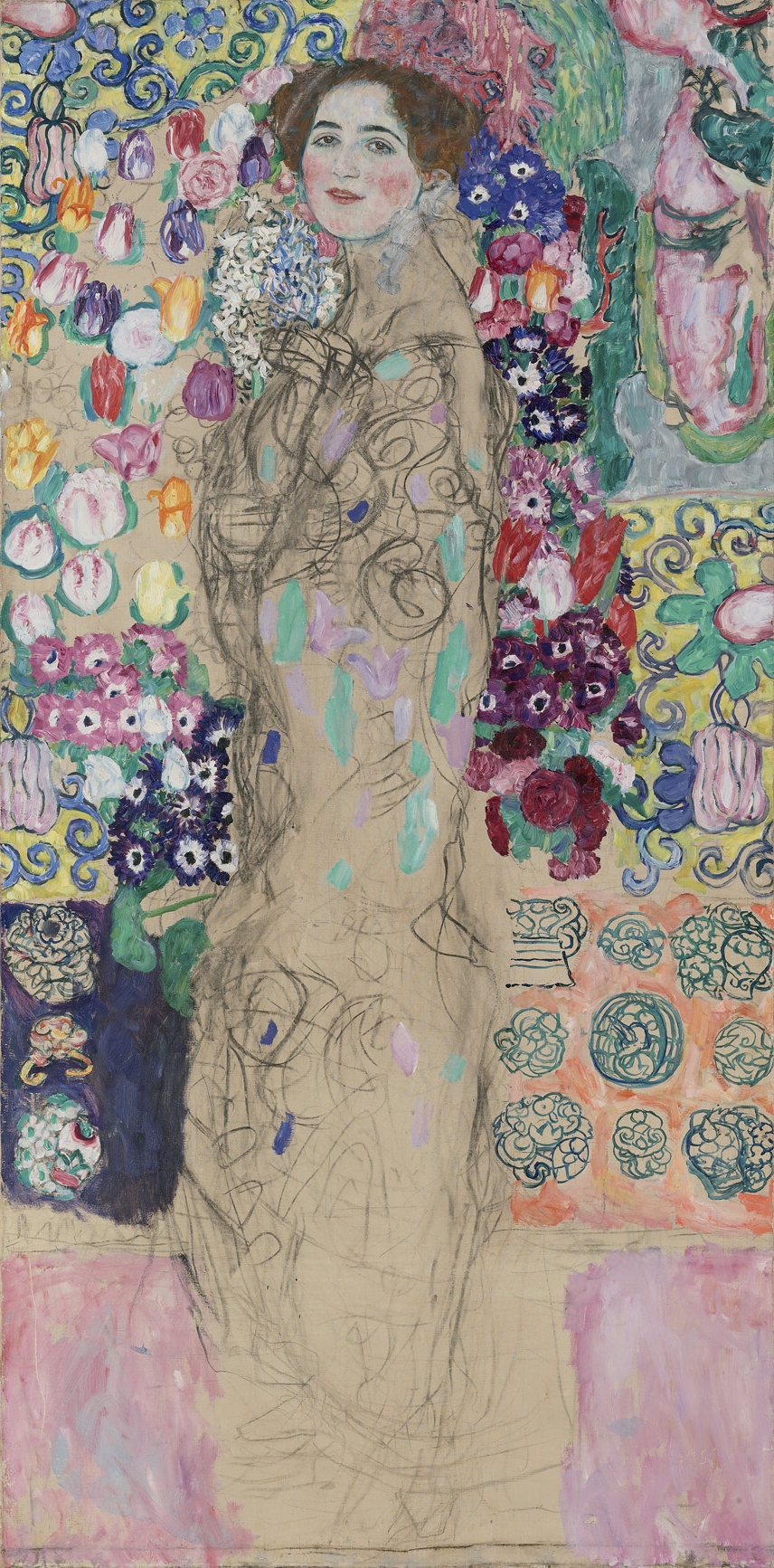

In the gallery of drawings, Klimt’s interest in the nude can be observed in the numerous preparatory drawings that line the walls. It is clear that Klimt’s close study of the contours of the human figure influenced several more detailed drawings of posed faces and hands that are on view in an adjacent room. Klimt’s series of drawings of Bloch-Bauer seated in an armchair depict a repetition of the pose that indicates the sympathetic nature of the relationship between the artist and the sitter. Klimt conveys movement by varying the thickness of his lines and draping clothing across the figures. Just as mesmerizing as the colors and patterns in the paintings from the previous gallery, the bareness and simplicity of the drawings of Bloch-Bauer also evokes an erotic and sensual quality.

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Ria Munk III, 1917 (unfinished). Oil and charcoal on canvas. The Lewis Collection.

The exhibition at the Neue Galerie provides an intimate view of Gustav Klimt’s relationship with his patrons. The Neue Galerie also introduces visitors to Klimt’s ability to derive influence from eclectic sources, including aspects of the earlier Symbolist movement and Byzantine mosaics—undoubtedly, this set Klimt apart from his peers and established a precedent for a new generation of artists. Positioning Klimt as a man of his time, above all, the Neue Galerie’s Klimt and the Women of Vienna’s Golden Age, 1900–1918 showcases how fin-de-siècle Vienna influenced Klimt, and how his drawings accurately reflect the opulence and eroticism inherent in the period.

—Carlos Bernabe, Development Associate at The Drawing Center