Edgar Degas is a name that most often brings to mind pastel tutus, delicate dancers, and the slanting floorboards of ballet studios. A Google search of the artist’s name yields almost exclusively these images: compositionally innovative glimpses of the ballet. Edgar Degas: A Strange New Beauty, organized by Jodi Hauptman at The Museum of Modern Art (on view through July 24th), introduces a departure from the well-recognized Degas: an innovative, experimental, and often unseen aspect of his oeuvre: monotypes. The exhibition features approximately 120 monotypes, as well as sixty related paintings, drawings, pastels, and prints, all depicting a wide range of subjects: smeared portraits, brothel scenes, blurry landscapes, and luminous bathers shrouded in darkness.

Degas’ fascination with motion and modernity is evident throughout the exhibition, and this is one of the reasons he was drawn to monotype from the mid-1870s to the mid-1880s, and again during the early 1890s. Monotype is a medium wherein the artist manipulates ink on a metal plate and then runs it through a printing press, resulting in a single impression. This process afforded Degas the opportunity to bring spontaneity, experimentation, and even recklessness to his examination of the different aspects of modern life, all of which had one thing in common: ceaseless, almost chaotic movement.

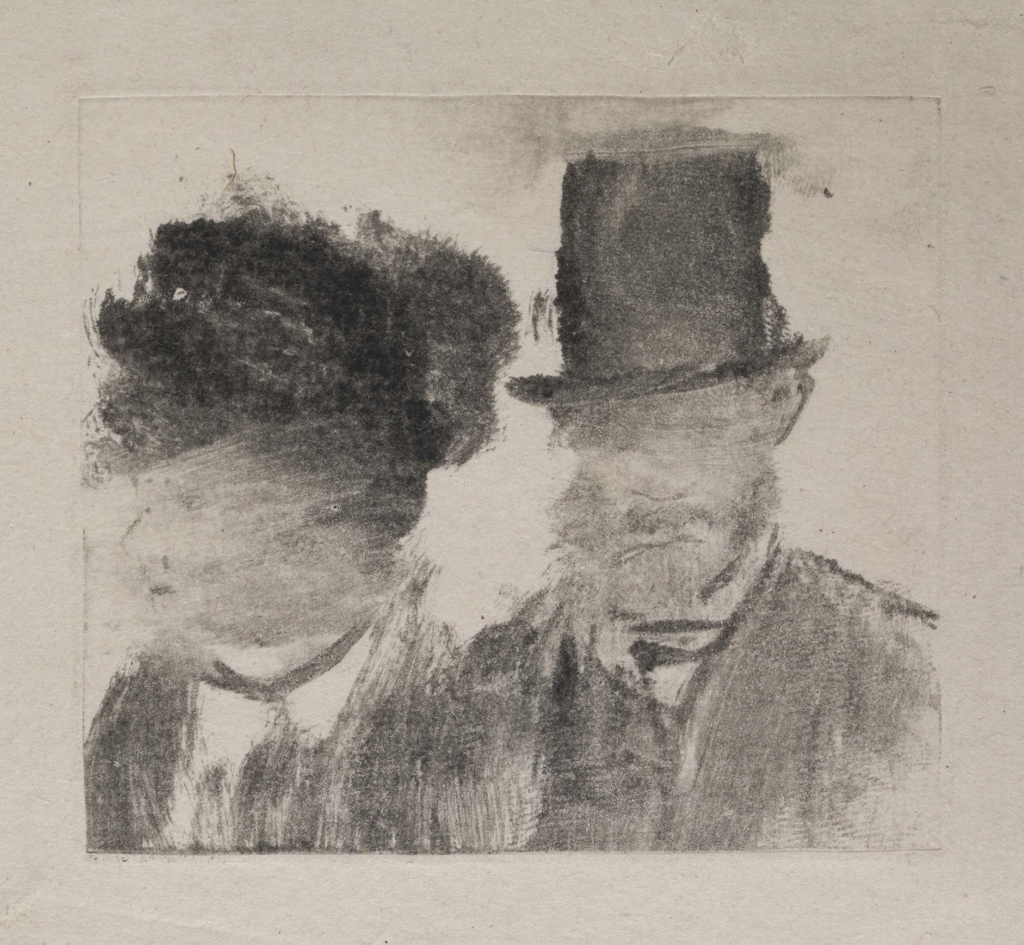

Edgar Degas (French, 1834–1917). Heads of a Man and a Woman (Homme et femme, en buste), c. 1877–80. Monotype on paper. Plate: 2 13/16 x 3 3/16 in. (7.2 x 8.1 cm). British Museum, London. Bequeathed by Campbell Dodgson.

One of the many highlights of the exhibition is Heads of a Man and a Woman (c. 1877–80). Although this work is prominently featured in promotional materials for the show, it is unexpectedly tiny; at about 3 inches square, this monotype features two subjects whose faces have been smeared in such a way that the viewer is plunged into the experience of passing strangers on a crowded street. This small piece is one of Degas’s many examinations of the frenetic activity of urban life. One gets the impression that, due to the size of this piece, Degas might have used a fingertip to smudge the faces before sending the minuscule plate through the press.

Indeed, throughout the exhibition, Degas’s range of mark making is put on display (there are even magnifying glasses available to anyone interested in going on a scavenger hunt for fingerprints). The flexibility of monotype, curator Jodi Hauptman has said, allowed Degas to expand his “drawing toolbox”; not only did he use brushes, but also rags, cards, fingertips, fingernails, and sponges to evoke movement on the metal plate, in turn transferred to static paper.

Edgar Degas (French, 1834–1917). Forest in the Mountains (Forêt dans la montagne), c. 1890. Monotype in oil on paper. Plate: 11 13/16 x 15 3/4″ (30 x 40 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Louise Reinhardt Smith Bequest.

Degas brought his exploration of motion through monotype out of the urban realm and into the countryside when he returned to the medium in 1890. Though the room dedicated to his landscapes seems at first like a respite from the scenes of modern life in the rest of the exhibition, upon closer examination one discovers that these pieces were created in order to capture the experience of watching hills and trees turn to blurs from the window of a moving train.

Forest in the Mountains (c. 1890) is one such landscape that beautifully illustrates Degas’ dedication to experimentation. For this and many other pieces from the early 1890s, he abandoned black printers’ ink for colorful oil paints, an unprecedented use of a medium not designed for printing. Oil paint also has a slippery quality that lends itself to smearing and blurring. However, as can be seen in the lower left corner of Forest in the Mountains, the wrong proportion of paint to plate sometimes resulted in large blots of color on the page. Degas was clearly not deterred by these accidents; he embraced their abstraction as part of the visual experience of the countryside flying by.

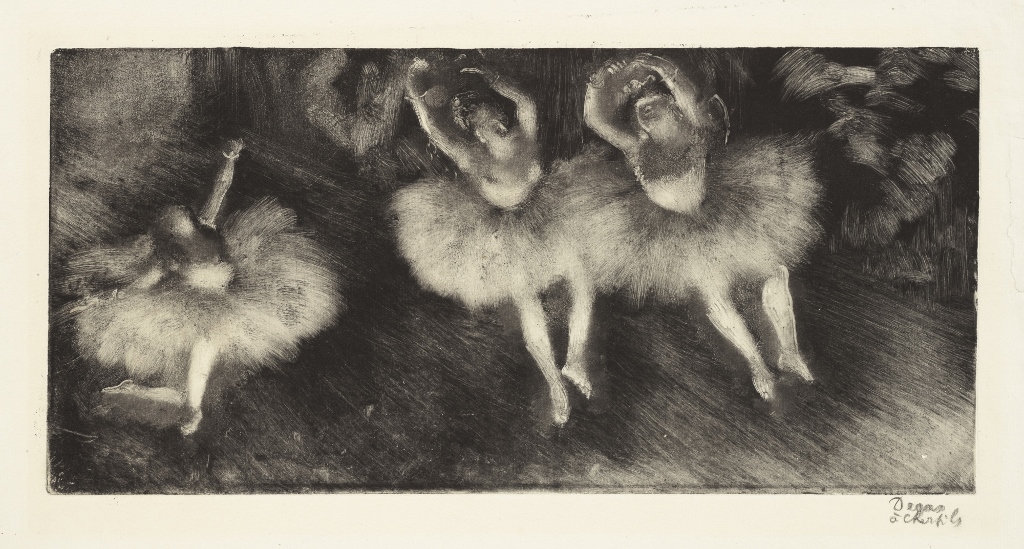

Edgar Degas (French, 1834–1917). Three Ballet Dancers (Trois danseuses), c. 1878-80. Monotype on cream laid paper. Plate: 7 13/16 × 16 3/8″ (19.9 × 41.6 cm). Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts.

A Strange New Beauty is not a complete departure from Degas’ more recognized work; the exhibition features monotypes of the ballet as well. However, the curators are careful to highlight the reason Degas was so often focused on these delicate, ephemeral figures: drawing ballet dancers was, according to Degas, “a pretext for rendering movement.”

—Allie Wilkinson, Curatorial Intern