T.C. Cannon: At The Edge of America, on-view at the National Museum of the American Indian through September 16, 2019 features paintings, drawings, prints, poems, and songs by one of the most important Native American artists of the twentieth-century: T.C. Cannon. Born in Oklahoma to Kiowa and Caddo parents, Cannon started art school in 1964 at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA). The cultural climate of the 1960s bolstered collective action among native peoples and several organizations were formed to induce visibility and change, including IAIA, which was established in 1962 with Cannon as one of its earliest graduates. The progressive curriculum of IAIA included experimental approaches to art making, which was influenced by both traditional native practices and modernist movements like Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art.[i] Faculty also encouraged students to use the contemporary culture and socio-politics as part of their artistic practice.[ii] Cannon addressed the complexity of native identity in his interdisciplinary oeuvre by addressing specific U.S. and native conflicts, rebelling against stereotypes associated with native art, and examining his personal history as a Vietnam veteran.

Along with more than 42,000 Native American soldiers, Cannon enlisted in the US armed forces during the Vietnam War, serving as a paratrooper in the 101st Airborne Division from 1967-68 and earning two Bronze Star medals. Cannon was conflicted about being a soldier during Vietnam—a conflict that he interpreted as a reiteration of America’s colonial past. Yet Cannon was proud to enact the traditional warrior role that is a prominent part of Kiowa culture. After his discharge, Cannon was honorably inducted into the prestigious Kiowa Ton-Kon-Gah, or Black Leggings Warrior Society.[iii] The paradox of fighting for the US army as a Native American is the subject of Soldiers, which features a splayed figure with split halves: that of the native and colonizer. Cannon, who used writing as an integral part of artistic practice, noted in the 1970s: “…by the simple and beautiful virtue of being Native American, with the blood of mountain and bird motivation, we still have to be soldiers in our homeland.”[iv]

Writing, along with drawing, painting, printmaking, and songwriting, were all mediums that Cannon explored interchangeably, and are all featured in the exhibition. Cannon’s poems and song lyrics are printed largely on the gallery walls alongside his paintings. In his studio, Cannon would listen to Bob Dylan, and would write poems and then create paintings, or vice versa.[v] Cannon’s poem Beef Issue and the corresponding painting Beef Issue at Fort Sill are examples of his signature interdisciplinary mode of creation. The lyricism of Dylan’s music greatly influenced the political directness and folksy style of Cannon’s poetry and songwriting, which deal with specific conflicts that are indicative of wider socio-political trends. While in the studio, Cannon would play guitar, paint, and write—sometimes paintings would become the basis of songs, or vice versa. In Beef Issue, Cannon writes:

“everything must be used

then else returned to the earth

for even now

the grass is black with blood

the rainsmell fills the breeze

and the children are hungry

i can see that the sky

is yellowing again

the fuzzy face soldiers are laughing

and they are never hungry

the dogs are eager for the bones

the sky is burning down overhead

everything must be used

the grass is black with blood”

Both the painting and poem refer to a period of nineteenth-century government food rationing during which southern Plains communities were legally forbidden from using customary hunting grounds, and were instead sent rancid meat in order to fulfill treaty obligations. The lurid painting depicts a dead cow wide-eyed in terror with its innards spilling on the ground. The landscape has a distorted perspective and features a Native American man holding a knife in one hand and shielding his eyes from the sun with the other. He peers out across the floating grass directly at the viewer and frowns in discernment. Cannon used specific conflicts like these as subjects in his artwork, but also renounced the expectations of native art through sheer, unencumbered creativity.

During the heyday of modernism, native artists began to reject the stereotypical expectations that the artworld had of indigenous art. Yanktonai Dakota artist Oscar Howe, in 1958, wrote a strongly worded critique to the Phillbrook Annual, which had rejected his painting. “Are we to be held back forever with one phase of Indian painting that is the most common way? Are we to be herded like a bunch of sheep, with no right for individualism, dictated to as the Indian has always been, put on reservations and treated like a child and only the White Man know what is best for him …. One could easily turn to become a social protest painter. I only hope the art world will not be one more contributor to holding us in chains.”[vi] Cannon was an artist that strongly held to these beliefs through his wide and fearless exploration of his own identity and the culture that surrounded him.

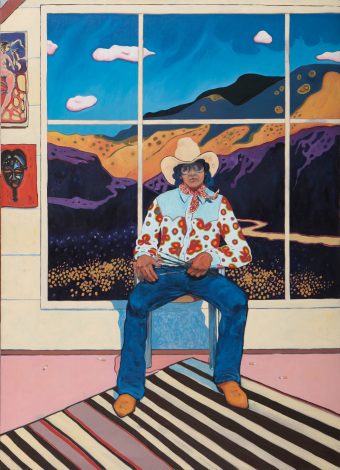

In Two Guns Arikara, the central figure, a Native American man, is wearing a bright, electrically colored U.S. military scout uniform with traditional Plains Indian accessories. Each piece of clothing is outlined in orange, blue, or purple lines that create a stunning clarity to the contours creating distinct shapes. The figure’s cascading lavender hair is overlaid on a darker, rich purple background patterned with gold hoops. The vivid and clear outlining creates flatness to the painting that looks to be made out of striking pieces of patterned fabric. The only dimensionality found is in figure’s face—shaded cheekbones, a serious furrow, and deep eyes that are seeing past something. “Arikara” refers to a Native nation related to Cannon’s Caddo ancestors, who suffered greatly during the Western colonial conquests in the nineteenth century.[vii] With his pistols pointing cross-directionally and sat upon a chair that looks to be part of the painting ground, this defiant and regally dressed man looks immovable. The strength of color and pattern, and the sitter’s powerful but humble presence is stoutly contrarian to the ethnocentric and romanticized black and white portraits of Native chiefs produced in the nineteenth century.[viii] These prolific photographs, taken by Euro-American men, position individuals from different Native American nations as homogenous people, and were staged with sitters wearing traditional garb as an inauspicious documentation of the so-called “vanishing race.”[ix] Cannon’s bright, self-made representation counterpoints the photographic portraits through a vital individualism and modernity.

The exhibition continues to showcase Cannon’s meandering oeuvre, including a hallway of intimate sketches and prints, and a reproduction of his sketchbook, which records his thoughts on art history, philosophy, and spontaneous sketches. In his poem, “Collector #3,” Cannon expresses the complex dynamics of nativeness, art history, and US politics.

“the world is at odds with itself

about situations like this

there is a lady in a room of no windows

there is a lady in a room purged of love

i am at odds with priests and worlds”

The encompassing exhibition even includes recordings of Cannon playing guitar which are played overhead. The artists’ voice sings out in a spirited croon like a troubadour searching for answers, and yet accepting the inevitability of inconclusiveness. T.C. Cannon died in a tragic car accident at the age of 31. His voice spoke truthfully about native issues and the complicated questions of identity that socio-political and cultural contexts create. Exhibitions that showcase peripheral artists like Cannon are importantly resurgent to artist’s efforts. Provoking the deeply troubling parts of U.S. history, Cannon’s work refocuses attention to the foundations of our country, and the difficult questions these facts give rise to. Contemporary viewers can look to Cannon’s works and words to walk parallel to him, and come closer to the edge on which he produced songs, words, and images.

“your tears will not be ready to recognize

the close paths we walked and will be

divorced from all night drunks and

following arguments contained by clocks

and empty bottles.

none will see my final grimace of pain

and smile of diamond clenched teeth bones

on that final bed of sand and cactus

out there where it gets lonely in the

early summer rain.

i will be in the desert

and you will be in the city when i die.”

-Kara Nandin, Bookstore Manager/Special Programs Coordinator

Poetry throughout by T.C. Cannon

[i] Besaw, Mindy N., Hopkins, Candice, and Well-Off-Man, Manuela, Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now (Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press, 2018), 9.

[ii] Wall text, National Museum of the American Indian, T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America, National Museum of the American Indian, New York, NY.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Besaw, Mindy N., Hopkins, Candice, and Well-Off-Man, Manuela, 8.

[vii] Wall text, National Museum of the American Indian, T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America, National Museum of the American Indian, New York, NY.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Voon, Claire. “A Rare Collection of 19th-Century Photographs of Native Americans Goes Online.” Hyperallergic. July 22, 2019. Paragraph 7. https://hyperallergic.com/434729/19th-century-photos-native-americans-american-antiquarian-society/.