Raissnia is performing with Panagiotis Mavridis this Saturday at The Drawing Center during the Basement Performances, curated by John Zorn

By Amber Moyles, Curatorial Assistant

I had the pleasure of visiting artists Raha Raissnia and Panagiotis Mavridis in their studio Sunday afternoon where we discussed techniques for expanded cinema and Mavridis’ original hand built instruments. After a private viewing of one of Raissnia and Mavridis’ pieces, a thirty-minute series of black-and-white film loops intermeshed with drawing and live instrumentation, I had the opportunity to speak with Raissnia about expanded cinema and the influence of avant-garde film on her drawings and installations.

Amber Moyles: Could you describe the term expanded cinema and the meaning of this term for your work?

Raha Raissnia: I see expanded cinema as a live event in which the artist engages in creating cinematic works in the presence of the audience. It is, we could say, a dense exploration of light as it manipulates cinema’s structural elements with regards to space, time, projectors, and screens. My own work with expanded cinema is layered and permutational. It incorporates other areas of my practice, which are painting and drawing. I make use of both old and new technologies, and I rely heavily on what my hands can achieve.

The piece that you and Panos will perform at The Drawing Center as part of Basement Performances is titled Mneme. What is the significance of the title for this work?

Mneme in Greek means memory. In Greek mythology Mneme is one of the three muses. She is memory personified. Her two sisters are Aoide, muse of song and music, and Melete, muse of study. When I finished making this work and showed it to Panos, he said it made him think of the way our memory works. The work is made out of pre-existing materials that I cut, painted, and collaged together, making something entirely new. So, after reflecting a bit, I agreed with him that, yes, this is in fact analogous to the way our memory functions; Mneme puts together bits and pieces from the past and forms new meaning in the present.

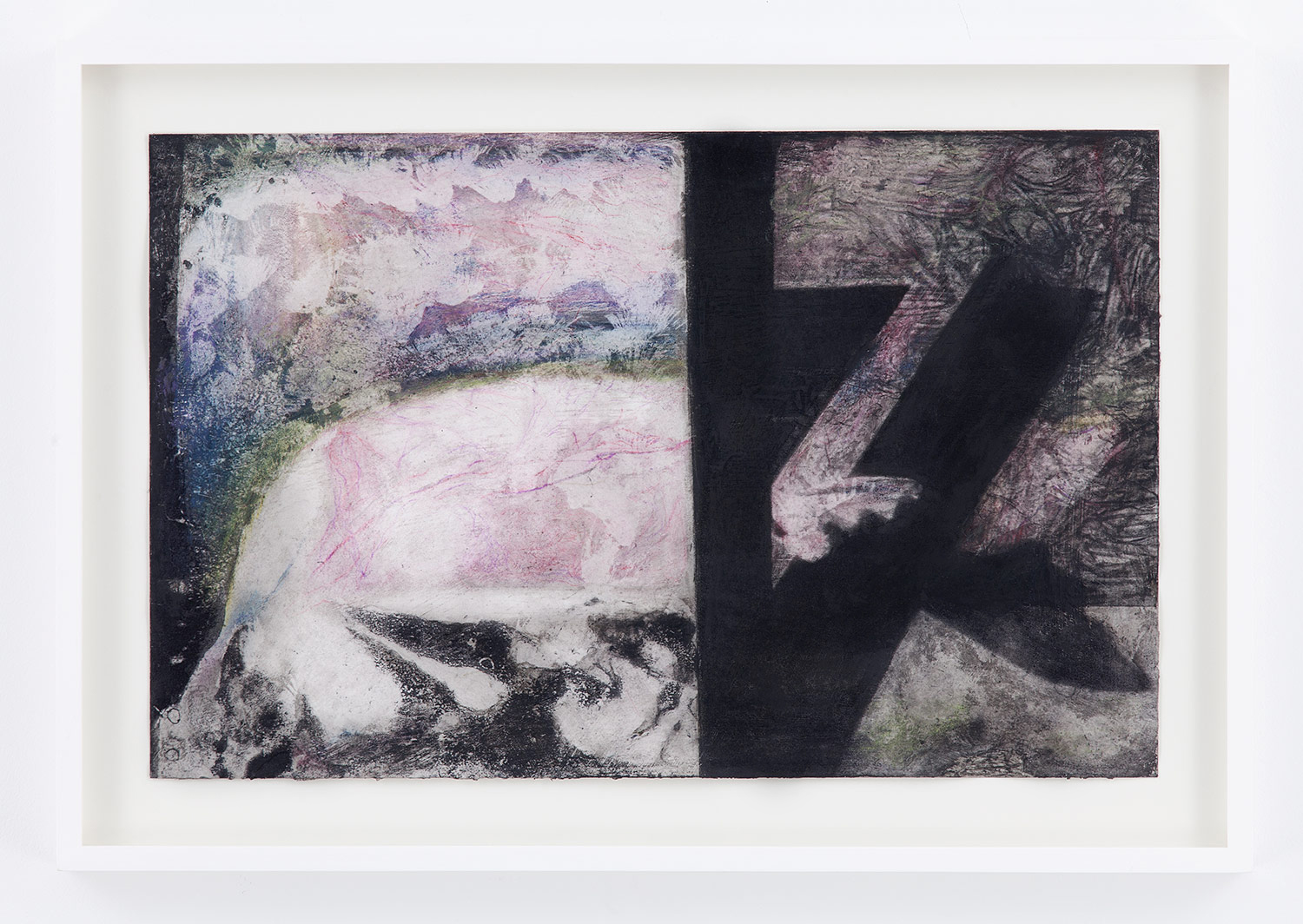

Raha Raissnia and Panagiotis Mavridis, Mneme, 2015. Projector and sound performance. Courtesy of the artist and Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York.

You worked at the Anthology Film Archives for a number of years. Can you describe the effect this experience has had on your work? Is there a particular film you came in contact with that has influenced your practice?

It’s been a long time since I worked at Anthology, but its influence on my work and life continues. Working there was an education, and through my experience I learned about the works of a number of significant artists who are known historically, but I also learned tremendously from the people who worked and showed there and who are now my great friends. Major influences have been works by Stom Sogo, Jonas Mekas, Harry Smith, Andrew Lampert, and Martha Colburn, to name just a few.

How has working with musicians and live instrumentation, and with Panos who constructs his own instruments, informed your work?

Music and sound play a major role in both inspiring and forming my works. In general, I aspire to the temporal and experiential condition of music‚ which are suggestive, abstract, and ambiguous. The work and sensibility of the musicians I collaborate with inspire me. Our collaboration is very focused but in a free manner in which we work independently. Rehearsal is key and it is becoming more and more important to me. I consider my projectors as my visual instruments that I play live, very similar to the way musicians play their instruments.

Movement, or the ability to embody motion, has been described as the essence of cinema. Your projection performances are both cinematic and still, combining characteristics of drawing (a static medium) and cinema. How would you describe the contrast between stillness and motion in your work?

Several aspects that belong specifically to drawing are used in my film works. One aspect is the direct hands-on manipulation of the photographic image on celluloid through both scratching or fading and the application of ink. The other aspect is incorporating pre-existing drawings done on paper through photography, filming, printing, and collage. And the final aspect of drawing used in my film is stillness. Because I mostly perform my film works, I can play with both stillness and motion. I can break apart the frames, create individual images as slides, make long strips of film that I can hand feed and manipulate. I can also slow down the frame rate from 24 frames per second to one frame per second and even pause on that for as long as I want. This is all done of course through the use of various types of projectors that are at times modified by hand.

There is a quote from Agamben that reads: “paintings are not immobile images, but stills charged with movement, stills from a film that is missing.” If the same could be said of your drawings, is it possible to describe the missing film from which your drawings would have been taken?

That is a nice quote, but there is no film missing from my drawings. They belong to the same world, with the same theme. What separates the two, drawings and film, is the overall composition. The drawings are a concentrated force whereas the films flow and transform. Each frame of the film longs for the next one to come immediately after.