I am fascinated by the old elevators of New York. Those heavy, unwieldy machines that lift one up to vintage factory-type places, possessed by the spirit of the industrial revolution. Betrayed by progress, gentrification, and global economy, or simply by the course of life, these spaces now serve all sorts of endeavors, while still embodying industrial promise.

Visiting them as art studios, these unequivocally modern places seem to be the remains of an ideal that is slowly passing away. No longer serving as paradigms of sophistication, these creaky artifacts still have the capacity to elevate extremely heavy loads – even unexpected contradictions.

Some of these elevators serve as testament to a major displacement. Instead of supporting serial production, they enhance the production of dissidence: conceptual displacements that help the queer to occur. In a similar manner, art can be a tool for dissent. This can be the case for any consciously autonomous practice of art, since the autonomy to create works against repetition.

Thus, as a fertile territory, the queer usage of an industrial structure can strengthen the practice of art, which is interested in creating imagery and narratives that help us understand the displacements of daily life. Articulating contradictions, linking the old with the current, erasing boundaries between ways of being, reconciling conflicts at any point; life seems to move out beyond our understanding.

Kerry Downey, Ajar, Single Channel Video and Stills, Collaboration with Joanna Seitz; Starring Pedro Osorio. 2013.

I am in front of one of those old elevators: its entrance opens at street level directly onto the sidewalk. There’s a sign to the right, “18th Century: 5th floor.” The fantasies created by my own excitement and the solitude of the streets make me think of another displacement, where I can actually enter another century once I reach the fifth floor. I am coming up, however, to another date: the one at the fourth floor.

I am here to visit the studio of Kerry Downey, one of The Drawing Center’s Open Sessions artists. She kindly comes downstairs to assist me getting on to the elevator. Kerry asks if I have a stick with me. I do not. She looks around on the ground, finds one, and opens the elevator. It is tricky to use, but still it is more comfortable than climbing the stairs. Here we are − the spirit of Modernity.

Downey’s studio is part of a collective space. “It takes some practice,” she says when I ask how it is to share such a space with others on a daily basis. Her studio has only three walls. In a way, it is always an open studio: a place useful to link “trash to loss, urine to the sublime, your grandmother to my girlfriend,” as she writes in her statement. I look around her studio and find myself in a calm atmosphere while we drink some tea. A beautiful, very long plant hangs from a corner on the ceiling.

“Invisibility as a way of the Queer,” she mentions at a certain point in our dialogue. I realize then that I somehow managed to overlook a set of drawings on the wall just to my right. These are drawings of movement: bodies and objects morphing into one another − coming across as flickering lines or expressive stains − proof of the failures when prosthesis of modern life falls apart. The faint light, the white paper over the wall, the unframed grey-toned drawings, the detachment from technical mastery: I find myself looking around her studio with the lens of a rigid structure ignoring my sense of curiosity. Right now, it is me who is being old fashioned.

Even though Downey has been a teacher of drawing, her work leads to an opposite direction from that of the expert’s figure of the “maestro”. Her practice seems to me to be a series of displacements, and of dissident landscapes that she has led from her own structures. I realize that I have been invited to abandon my own expectations, to displace my sight from the achievement to the happening.

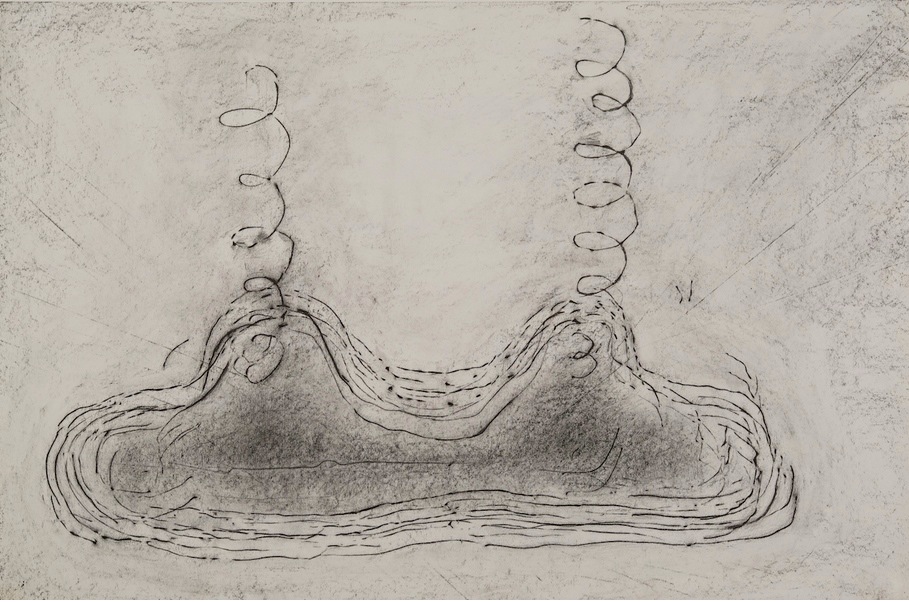

Some of her drawings particularly capture my mind. Territories is a series of drawings half-abstract, half-figurative, which are made with hot glue. Once the glue has dried, Downey uses the surface to mark the paper with graphite. Rubbing the paper to create the resulting image, the artist discourages the static structure of her own drawing and encourages the appearance of other traces and trails, which form other displacements. Her technique reminds me of Gyotaku, the old Japanese method of recording catches while fishing when they release the fish after rubbing them.

Permanently linking the body to the architectural, the modern to the organic, the heavy to the volatile, desire to indifference: her videos, drawings, and photography seem to me a prologue for a phenomenology of the dissident. It is about surrealism. It is a series of momentums to melt the clock; an impulse to twist what is straight. It is also expressionism: a system to record the stains left by the displacement of a paradigm. The result of using old structures to elevate what has already been abandoned by the heavy loads of time.

Kerry Downey, To Do list, Video and photography, in collaboration with Jen Rosenblit and Joanna Seitz. 2012-2013.

— David Anaya Maya