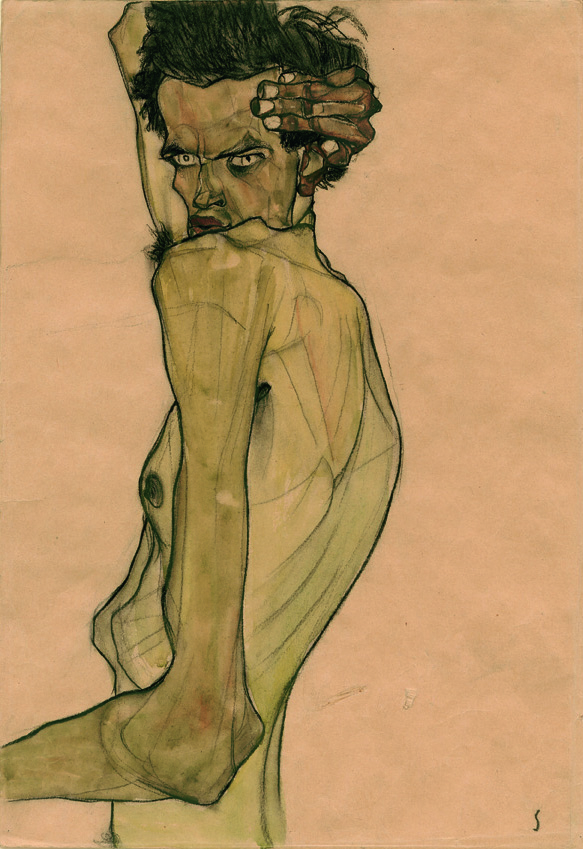

Egon Schiele, Self-portrait with arm twisted above head, 1910. Watercolor and charcoal. Private Collection. Image courtesy of Neue Galerie.

“The painter can also look. To see however is something more.”

—Egon Schiele

Does Egon Schiele ever go out of style? Certainly his fretful line and his provocateur’s attitude speak to everything we think of as “modern.” And with recent major exhibitions at London’s Courtauld Gallery and New York’s Neue Galerie, it seems like he’s everywhere at once.

The Neue Galerie exhibition, Egon Schiele: Portraits has been extended through April 20, 2015, and it’s definitely an exhibition to see before it goes. Although Schiele was one of a number of Austrian artists redefining portraiture at the beginning of the twentieth century, this exhibition, curated by Dr. Alessandra Comini, presents him as the artist most consistently engaged in overturning conventional portraiture to examine the psyche quivering underneath.

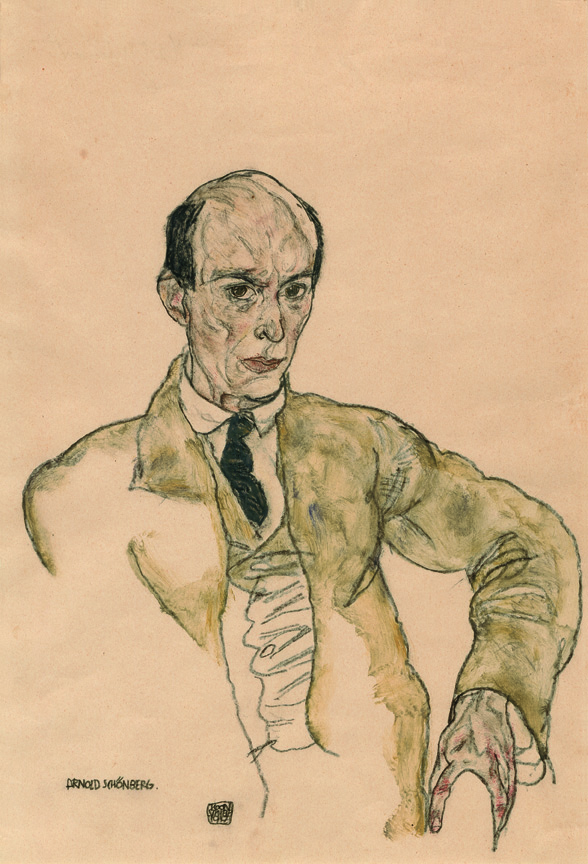

Egon Schiele, Portrait of Arnold Schoenberg, 1917. Watercolor, gouache, and black crayon. Private Collection. Image courtesy of Neue Galerie.

Organized in six thematic groups—Family and Academy, Fellow Artists, Sitters and Patrons, Lovers, Eros, and Self-Portraits and Allegorical Self-Portraits—the exhibition opens with a series of dutiful charcoal drawings from Schiele’s days at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. In the context of those drawings, three spellbinding portraits of artist Karl Zakovšek from the watershed year of 1910 are utterly unlike anything Schiele had done before. In two charcoal and watercolor studies, Zakovšek’s body is briefly sketched in contour line; the detail and focus is carried by the head and hands. Almost Mannerist in their attenuation, the gnarled hands and immense head show that Schiele was clearly not interested in realistic rendering—what you could look at—but in trying to see something more.

Schiele’s early Expressionist portraits place the sitter alone, in an unarticulated space, without any of the settings or props that might suggest her or his social standing, or even identity. Often the sitters are cropped, with hands or arms or bits of head cut out of the frame. In one extraordinary drawing of fellow artist Max Oppenheimer, the sitter’s whole body, save for one hand and one knee, is compressed into the top half of the frame. In some works, the slightest contour lines hint at a body, as in an arresting pencil drawing of Elisabeth Lederer and several drawings and watercolors of her brother Erich. All of the distorting, severing, excluding, seems to be consciously or unconsciously supporting the idea that Freud, Schiele’s contemporary, was exploring—that there’s more to anyone than meets the eye.

Installation view of Egon Schiele: Portraits, Neue Galerie, New York, NY (October 9, 2014 – April 20, 2015).

Schiele’s jittery, agitated, and anxious line epitomizes the decadent and crumbling Austro-Hungarian Vienna in which he lived and worked, but it also resonates with the impatience and unease of our own time. Egon Schiele: Portraits shows how he put that line in the service of a restless exploration of what portraiture can do.

—Champ Knecht, Deputy Director for Administration