I am both an admirer and a skeptic of Thomas Hirschhorn’s monuments, which he erects in unpredictable public spaces to honor philosophers and political thinkers. In the past, Hirschhorn has constructed monuments for Baruch Spinoza (Amsterdam in 1999), Gilles Deleuze (Avignon, France in 2000), and Georges Bataille (Kassel, Germany in 2002). The most recent monument commemorates Antonio Gramsci, an Italian writer, politician, political theorist, philosopher, sociologist, and linguist who lived from 1891–1937.

The Gramsci Monument is a sprawling construction made from unpainted plywood and other construction materials—a temporary encampment that resembles an Occupy protest site from the recent past. Like Hirschhorn’s earlier monuments, this one has a mission: to bring art to an underserved population, the Forest Houses, a public housing complex in the south Bronx. However, the extent to which an artist’s project can serve the real needs of such a community, or even inspire its residents to engage with art, remains up for debate.

During my visit to the site I noticed that Thomas was hanging around so I approached him. I began the conversation by asking, “Would you object to my thinking of the Gramsci Monument as a ‘drawing?’” He looked at me blankly. I told him I had recently started working at The Drawing Center and I was interested in talking to other artists about expansive drawings that abandoned traditional tools. I shared my observations of the monument, noting many different ‘lines’ mapping a visitor’s (or “tourist’s”, the locals’ name for outsiders) experience through the installation.

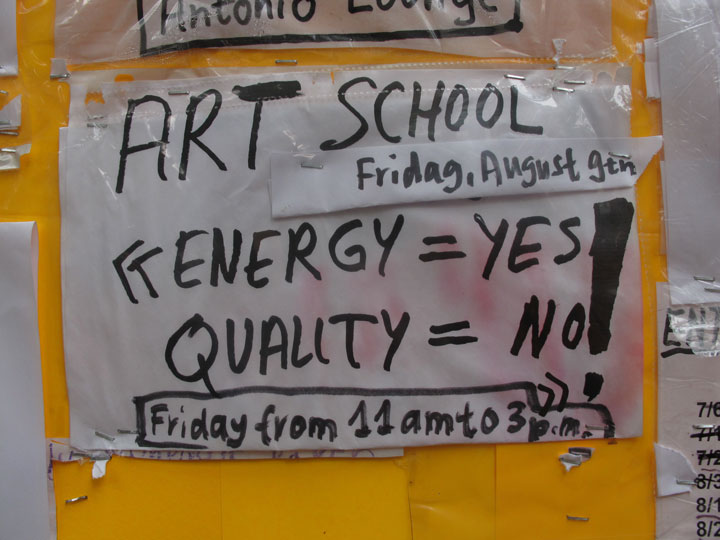

The rawness of the plywood platforms, the taped joints (a signature mark of Hirschhorn’s monuments), and the many handwritten signs echo the ephemeral and coarse gestures that characterize drawing studies and drafts. As the viewer makes his/her way through the monument, s/he has the impression of moving through a three dimensional sketch. I asked Thomas if he had any thoughts on the draft-like qualities of his structures. I wondered if the Gramsci Monument was in fact a reworked idea from the Musée Précaire Albinet, an earlier project he constructed beside a housing project on the outskirts of Paris in 2004. There, works of art were borrowed from the Pompidou Museum and exhibited in a makeshift structure that shared the aesthetics of the Gramsci Monument.

Thomas told me that I was welcome to think of his piece as a drawing, but he hadn’t—and clearly wouldn’t—consider his monument to Gramsci in any other terms besides his own, focused on “presence and production.” He said the monument would be a success if he were present there every day, and if it provided many different channels of production for the community to engage with: a daily newspaper, a radio station, art workshops, performances that included an open mike and a daily philosophy lecture, a computer lab with internet, a café, and a library. Thomas said that he reestablished his presence every day, though when I asked him to clarify, he spoke in circular ways about being present without judging the circumstances or the conditions of life in the public housing project.

Thomas Hirschhorn, Gramsci Monument (philosophy lecture), installation view. Photo courtesy of Lisa Sigal.

The piece is rife with contradictions. Does the cultural experience engage the people who live in the projects, or is it a platform for tourists fetishizing Marxist theory? What real or lasting benefits does it bring to the community? Maybe these questions are the drawing—an imperfect fiction, an abstraction of place, an ideal that nudges against the reality of the Bronx. I want to believe that the Gramsci Monument is inherently a visionary drawing, a testing ground for an idea that is not fully formed but has vast potential.

–Lisa Sigal, Viewing Program Curator

The Gramsci Monument was active from July 1 through September 15, 2013. Thorough documentation can be found on the project’s website.