A few weeks ago I visited The Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, a nine-week summer residency program for artists in Skowhegan, Maine. I have spent multiple summers there in different roles: Participant (or Student, as we referred to it back then), Dean, Librarian, Resident Artist, and Resident Artist’s spouse. Let’s just say I have special feelings for this art camp.

This summer I was particularly interested in meeting with artists that are involved with drawing because of my current position at The Drawing Center curating the Viewing Program. While there, I met with a number of interesting artists including Viewing Program artist Harold Mendez. I was curious about how being at Skowhegan, in a studio beyond the cow pasture, would impact his work and drawing practice.

On the walls of Harold’s studio an assortment of diverse works on paper, mostly in shades of gray to black, were tacked in a line circling the space. From afar the images have similar properties, but close up they are varied and function as puzzle pieces. The line of images proposes to be read like a line of writing.

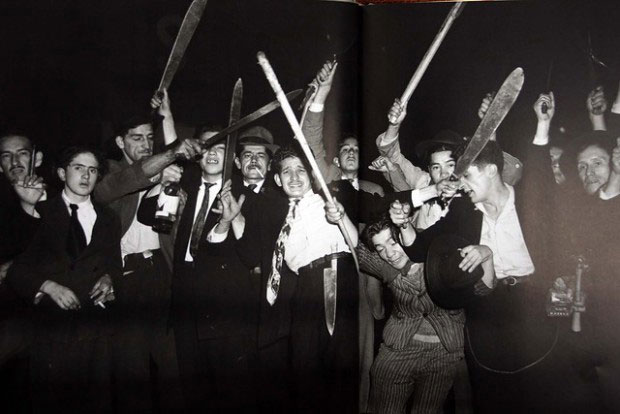

Some of the more explicit images come from an historical archive of photographs from La Violencia, Colombia’s ten-year civil war (1948–58). Harold has spent time in his mother’s childhood home of Medellin researching the archive and contemplating how to incorporate violent images from the days of Colombia’s drug cartels into his art.

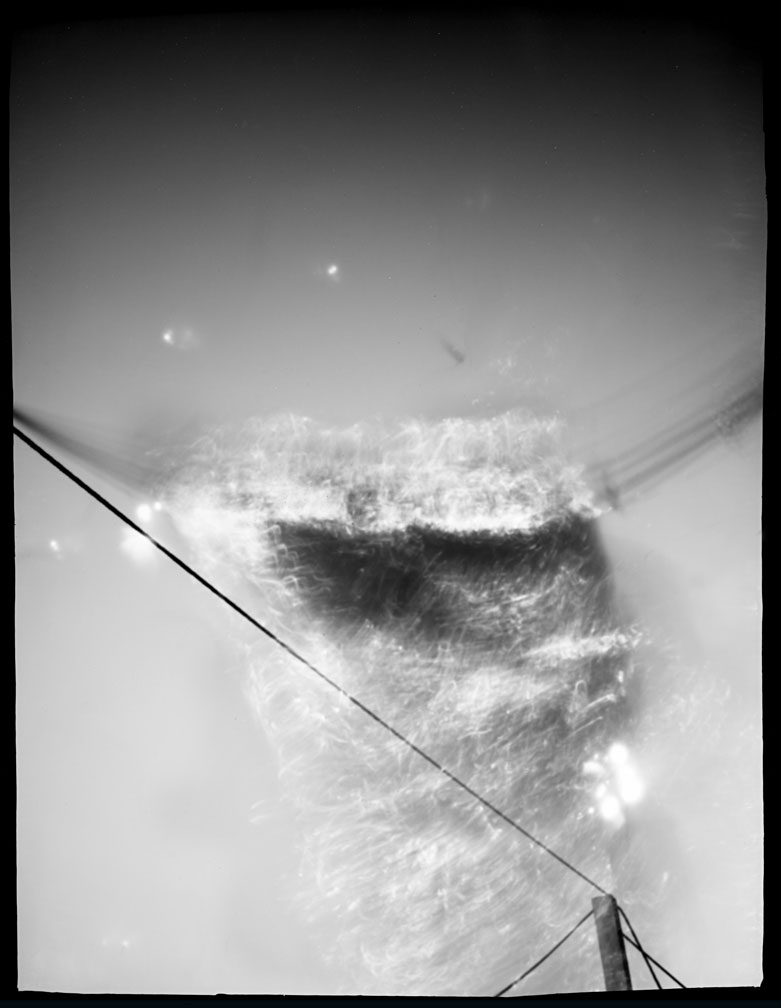

Adjacent to the photos in his studio there are semi abstract landscapes made with a pinhole camera. An obscured figure is reflected on and into the landscape. Harold calls these photos Specters. He has also been making dense pieces with layers of painted window screens, used dryer sheets, duct tape, and tinfoil. He transforms these mundane materials to a magical effect.

Black and white photographic negative from La Violencia archive in Medellin, Colombia. Image courtesy of Harold Mendez.

Harold Mendez, Work in progress from Specter series, 2013. Digital print transferred from unique pinhole photograph, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the artist.

Black and white photographic negative from La Violencia archive in Medellin, Colombia. Image courtesy of Harold Mendez.

Harold Mendez, Work in progress from Specter series, 2013. Digital print transferred from unique pinhole photograph, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the artist.

I was interested in contemplating how the archival images of La Violencia in combination with Harold’s abstractions suggest a narrative that links disparate stories across time and place. The grisly nature of the Colombian photos cast a shadow over his body of work, transforming the benign atmosphere and textured surfaces of his pinhole photographs into treacherous documents.

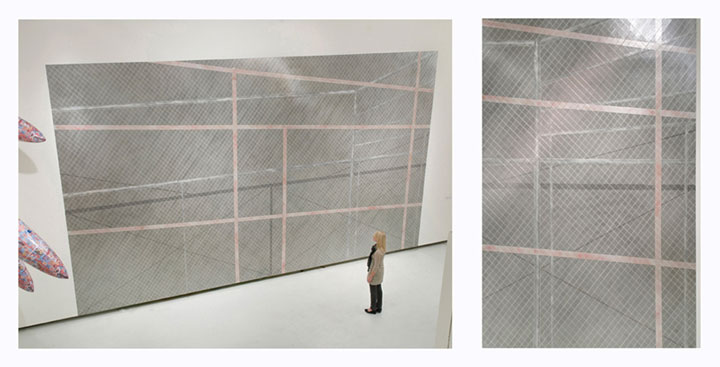

Harold’s drawing practice is most readily appreciated in To leave, to escape, is to trace a line, an installation which is featured in the Viewing Program’s online registry. In it, a wall’s surface is delineated with strips of duct tape, transforming a room into a drawing. The woven texture and width of the duct tape suggest slight outlines and divisions in the room. Depending on the viewer’s vantage point, these divisions could be seen as metaphorical and imaginary. However, in light of Harold’s other explicit, political images, responding to the tape drawings’ associations to real boundaries made by screens and fences seems justified.

Harold Mendez, To leave, to escape, is to trace a line, 2008. Mixed-media installation, acrylic paint, spray enamel, black silicon carbide, biaxially oriented insulation tape, and strapping tape, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the artist.

Using this same logic, I appreciated seeing Harold’s studio work at Skowhegan as contingent, with one piece referring to another for meaning. In some works like Let the shadows in to play their part, the drawing is texture created by veils of repurposed window screen. In other works the ‘drawing’ is an invisible diagram that links the historical photographs to the more process-oriented works in the Specter series.

Harold Mendez, Let the shadows in to play their part, 2012. Mixed-media installation, eucalyptus bark, black silicon carbide, water-soluble ink, marking chalk, spray enamel, and latex paint, 144 x 240 x 6 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

I came away from the studio visit thinking about the freedom that Harold has managed to cultivate in his art and how he has articulated diverse impulses with a consistent tone. Harold recently created an archive of his own work which he integrated with appropriated writing. The archive, which takes the form of a book but almost functions like a museum, seems to be a breakthrough for Harold.

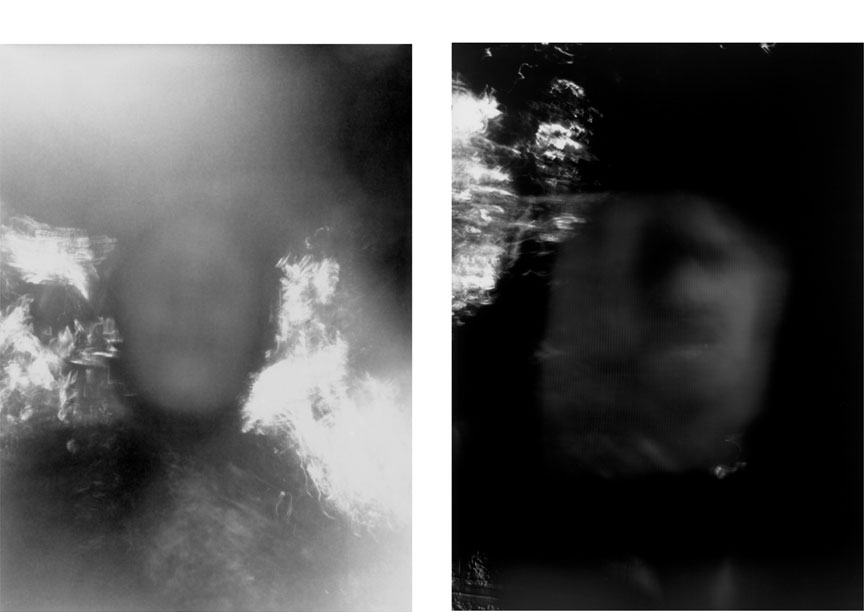

For instance, he used the archive as source material for a performance called Texts For Nothing / Textes Pour Rien, a fictional conversation between two characters: Braille Teeth, named after a phrase that Jean-Michel Basquiat used in paintings and street tags, and Nobody from the film Dead Man by Jim Jarmusch. The archive has given Harold the structure to link writing, performance, two-dimensional images, and his large tape/drawing installations into a physical and conceptual repository. I am curious about how his approach to drawing will continue to enrich and clarify his desire to create narratives that cross conventional borders of meaning and form.

Harold Mendez, I’m not always fitting (Portrait for Nobody (left); Portrait for Braille Teeth (right)), 2012. Diptych of chemically altered and processed pinhole negative paper prints, exposed from reflective mylar, 50 x 38 inches each. Image courtesy of the artist.

–Lisa Sigal, Viewing Program Curator

See more of Mendez’s work at his website.