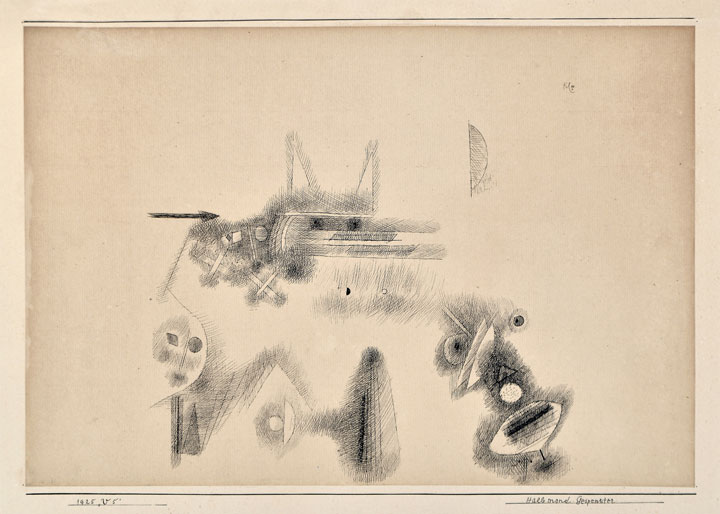

Paul Klee, Halbmondgespenster (Half-Moon Ghosts), 1925. Ink on cardboard, 8 1/2 x 12 1/2 inches. Image courtesy of Moeller Fine Art, New York-Berlin.

The work of Paul Klee (1879–1940), noted for its delicacy and wit, isn’t always honored with the distinction that it deserves. The Swiss-born artist, whose works loosely reflected his Cubist and Bauhaus affiliations, made playfulness a source for risk-taking and privileged drawing as a primary aesthetic feature in his art, even when working in paint. Through June 14, Upper East Side gallery Moeller Fine Art presents Paul Klee: Early and Late Years, 1894–1940, where viewers can take in small works from both the academic start and the grand finish to Klee’s career.

Despite the visible evolution in the exhibition, Klee’s hand doesn’t deviate wildly in its half-century journey. In his mid-career drawing Die Pflanze als Saemann (The Plant as Sower) (1921), the artist’s wavering interest in Surrealist imagery is occasionally visible. In the work, pots of soil are bases for plant-like figures. One pot dominates the drawing while the plant’s odd cantilevered arm drops seeds from claw-like fingers onto the earth below. Differentiated line weight and intermittent stippling, showing a break from the edge-to-edge buzzing of earlier and more resolutely Cubist works, forecast the bold assuredness of his late drawings, which bookend the show at Moeller.

Klee’s few writings on art are enlightening. In 1924, he wrote a short treatise entitled “On Modern Art,” which expressed his desire to make and see work that was formally situated—conscious of balance, color, and light—but also thoroughly rooted in an artist’s own sense of personal transcendence. He writes, “Presumptuous is the artist who does not follow his road through to the end. But chosen are those artists who penetrate to the region of that secret place where primeval power nurtures all evolution.”[i] Klee’s late works, hung in the entrance of the show at Moeller, achieve this state of fulfillment.

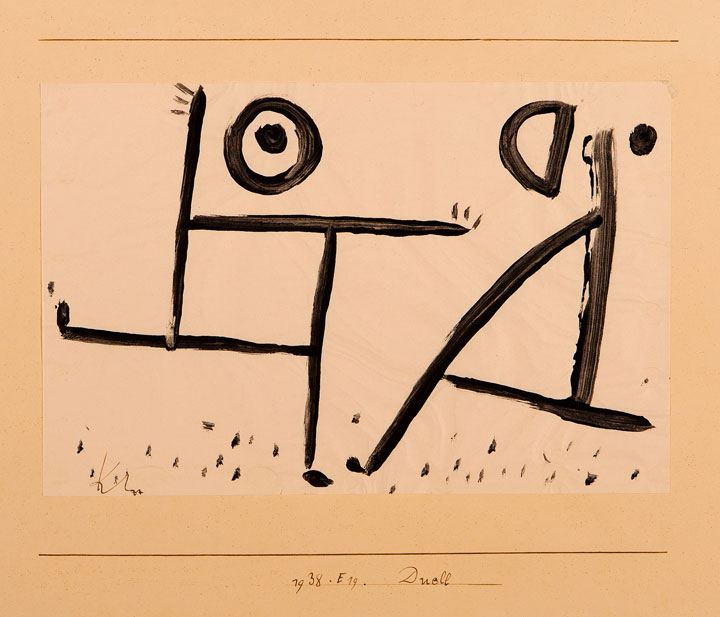

Paul Klee, Duell (Duel), 1938. Paste color on paper on cardboard, 7 x 11 inches. Private collection. Image courtesy of Moeller Fine Art New York-Berlin.

Created in paste color on buff or cream paper, the late drawings are unfettered and clear. Klee’s sense of whimsy is wide-ranging—full of bright expanses and dark corners—containing as much distant misfortune as instant optimism. In Duell (1938), made just two years prior to the artist’s death, figures, if present at all, never fully articulate themselves—nor do they lapse into full abstraction. By this period previous undercurrents of Surrealist imagery had dissolved and, with all previous modes of working depressurized, something emerged that was distinctly Klee.

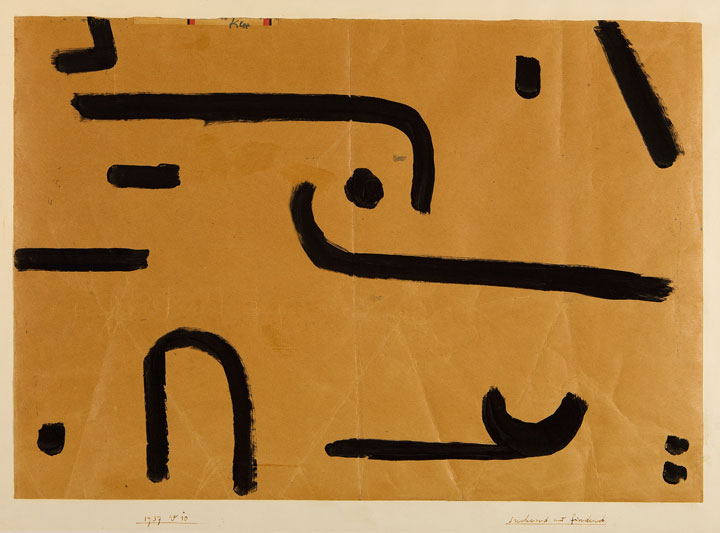

In deteriorating health, the artist made his last works free of canonized aesthetic traditions—unchaining himself from the hallmark traits of his lineages. The final drawings, like suchend und findend (Searching and Finding) (1937), embody a resolute energy on paper and, like his writing implies, allude to having found an unencumbered “secret place” after a life-long search. The place Klee found was airy, benevolent, and filled with generous invitation.

Paul Klee, suchend und findend (Searching and Finding), 1937.

Paste color on paper on cardboard, 13 3/4 x 19 5/8 inches. Private collection. Image courtesy of Moeller Fine Art New York–Berlin.

–Matthew Farina, Guest Contributor