Bookstore Manager Chloé Wilcox interviews librarian Andrew Beccone, founder of the Reanimation Library, a collection comprising books that have fallen out of routine circulation—including hobbyist and instruction manuals, general interest encyclopedias, textbooks and the like—selected for their remarkable visual content. The Drawing Center’s ongoing programming series Drafts derives from responses to images culled from the Reanimation Library by a sequence of cultural producers.

Shelf at the Reanimation Library in Gowanus, Brooklyn. Photo: David Lang. Courtesy of the Reanimation Library.

Chloé Wilcox: The Reanimation Library houses books which other research and reference institutions have deemed irrelevant or outdated, and thus discarded. Do you indiscriminately accept “outdated” books into the collection, or is there a vetting process—which books do you discard?

Andrew Beccone: I don’t really discard books because I’m fairly selective about what I acquire. I’m primarily interested in visual material, so that means that there are a lot of subject areas that I simply don’t collect. The library doesn’t contain much in terms of foreign policy or banking law, for instance. Of course there are many subjects far from art that do incorporate visual material—technology, the natural sciences, medicine, sports, to name a few—but even within those areas, I tend to be quite discriminating. The process is largely subjective and a number of factors can influence my decision to acquire a book, but I try to keep the overall balance of the collection in mind.

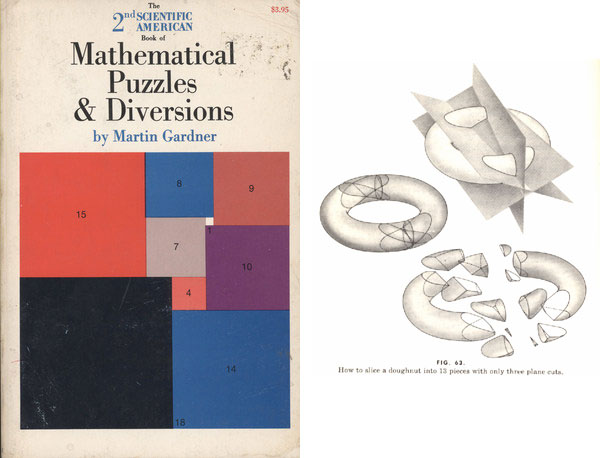

Martin Gardner, The 2nd Scientific American Book of Mathematical Puzzles & Diversions (cover and excerpt), 1961. Published by Simon and Schuster; New York, NY. Image courtesy of the Reanimation Library.

CW: How did this project originate? What initially interested you about “outdated” or “obsolete” books?

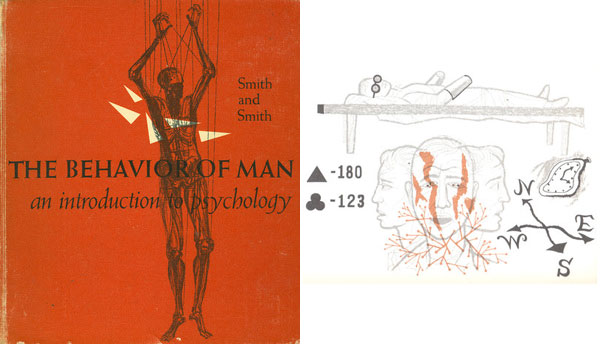

AB: The collection began after I came across a book called The Behavior of Man at a thrift store in 2001. At the time I was working at a library where, among other things, I spent a lot of time scouring its holdings for source material which I used to generate visual art. This library wasn’t particularly interesting from a visual standpoint, so once I encountered The Behavior of Man, I became determined to build a collection more suited to my aesthetic interests. After acquiring books for about a year, it occurred to me that the potential of the collection would become much more dynamic and unpredictable if I made it public; I suspected that it would appeal to other people, and that they would likely interact with it in ways that I wouldn’t, and in ways that I couldn’t anticipate. The library—somewhat to my surprise—began to synthesize two previously distinct elements of myself—artist and librarian.

I first encountered “outdated” books when I was quite young. My mother (now retired) was a librarian and she would occasionally bring home discards from the library where she worked. When I was 10 or so, she brought home a World Book Encyclopedia set from the 1950s that made a profound impression on me. I spent many, many hours looking through it. I’m not entirely sure why I was initially attracted to it, but the peculiarity of its visual material held genuine appeal. I remember being struck by the way that all of the paratextual content (the typography, layout, images, graphic design) worked in tandem to communicate its age—how it made the book look old.

Karl U. Smith and William M. Smith, The Behavior of Man: An Introduction to Psychology (cover and excerpt), 1958. Designed by Donald M. Anderson. Published by Henry Holt and Company, Inc.; New York, NY. Image courtesy of the Reanimation Library.

CW: Are you purely interested in what artists today can generate from the images and books in your collection? Or do you think these books and their visual programs maintain some kind of pertinence in their own right—insofar as they reveal how images make meaning and how we are affected by that?

AB: I think that books are captivating, complex objects not just because of the information that they contain, but because of how they also reveal the evolution of our thinking about particular subjects over time. They remain embedded with the language, assumptions, ideologies, and visual strategies of their times. We’re living in a moment of intense confusion about the continuing relevance of printed books, but I think that one way to consider their future is to think about their past. Electronic information is tremendously flexible—a characteristic that most people probably consider to be an advantage over print, but the relative stability of print has value too. I’m not quite ready to entrust all human knowledge to the cloud.

I started the library in part because I’m interested in the potential for creative, adaptive reuse of the books in the collection. I’m a huge proponent of the generative capacity of libraries. But I also think that there are many other good reasons to save and engage with the cultural materials of recent history. A book’s intended use is not its only use.

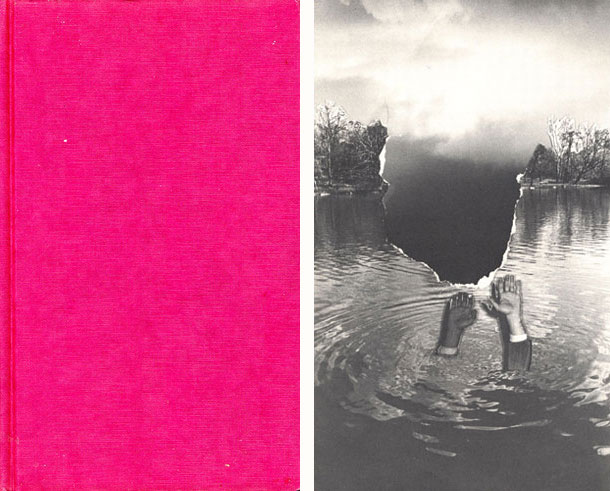

Daniel Cohen, How to Test Your ESP (cover and excerpt), 1982. Published by E. P. Dutton; New York, NY. Image courtesy of the Reanimation Library.

CW: You mention that this project has melded the librarian in you as well as the artist, two elements you had previously seen as very distinct. How have the larger artist and librarian communities received the Reanimation Library? Have you noticed different reactions to the blurring of traditional archival work and experimental projects?

AB: In general artists are more receptive than librarians. It’s worth noting that every branch library that I have set up has been in a gallery space rather than a library. That’s not to say that there hasn’t been any interest from the library world, but—to generalize again—this often falls along generational lines, with younger librarians being more receptive than older ones. I have 20 years of library experience, so it can be frustrating to encounter resistance from the field, but in some ways it doesn’t surprise me. The art world, on the other hand, has largely been receptive and supportive. To some extent, this can probably be explained by the art world’s embrace of interdisciplinarity, but I also think it has to do with the fact that many artists maintain collections of source material, so they often understand the library on an intuitive level.

There’s a curious internal tension in the library that is rooted in these two-fold components. On the one hand, the sum project of library classification is reductionist: a book—which obviously can be about many different things—must ultimately be situated on a shelf in relation to other books according to the logic of its particular classification scheme. It can’t be in multiple places at once. The library as a whole, however, plays with and resists this narrowing impulse; if it were a book, it would be difficult to catalog.

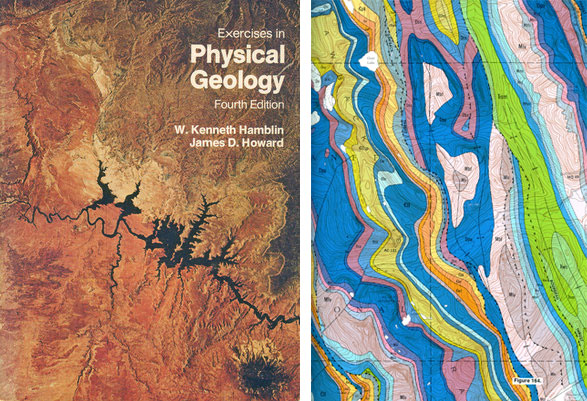

W. Kenneth Hamblin and James D. Howard, Exercises in Physical Geology, Fourth Edition (cover and excerpt), 1975. Edited by Robert E. Lakemacher and Ann Seivert. Designed by Dennis Tasa. Published by Burgess Publishing Company; Minneapolis, MN. Image courtesy of the Reanimation Library.

CW: On the About page of the Reanimation Library website, the German word for reference library, Präsenzbibliothek, is deliberately mistranslated into “Presence Library”—“something that exists in the physical world.” How would you distinguish the kind of “existence” or “presence” The Reanimation Library embodies as opposed to that of other institutions? Why is it important to emphasize these books’ presence?

AB: The obvious approach would be to scan all of the books, put them online and not worry about all of the time/space/money-consuming activities that are involved with housing a physical collection. But I’m interested in the tangibility of the books that I collect, and feel that it’s important to create a place in the real world where people can interact with them and with other people. I would never claim that the library somehow embodies presence in a way that is significantly different than that of other physical institutions, but I employ the phrase in order to emphasize its analog facets.

That said, I love the Internet. I spend far more time interacting with it than I’d care to admit. I’ve worked carefully to create a website for the library that reflects its offline sensibility without trying to replicate the experience of visiting the physical collection. Each medium has its advantages and its drawbacks, but I see no reason that one has to win out over the other and that they shouldn’t exist simultaneously.

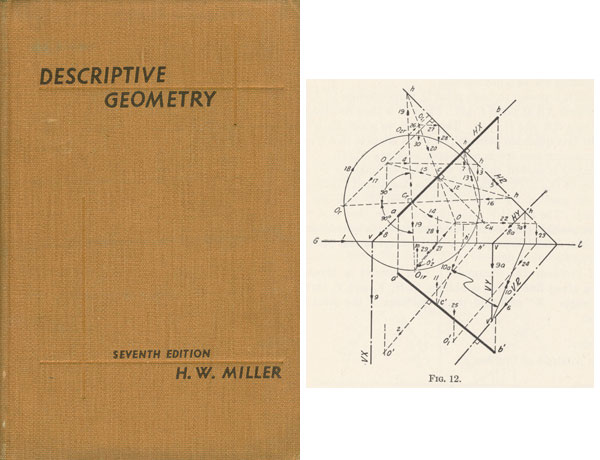

H. W. Miller, Descriptive Geometry, Seventh Edition (cover and excerpt), 1941. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York, NY. Image courtesy of the Reanimation Library.

CW: There seems to be an interesting tension between tangibility and visibility—in the recovered object of the book and the presence of the images online and in the library—with a sort of transience and invisibility, since not all the projects that use the Reanimation Library as a resource are explicitly visual. For example, The Drawing Center is currently doing a series of public programs called Drafts, which uses a shifting series of images drawn from the Reanimation Library as a starting basis to which artists, writers and performers respond in various works. The works that constitute the final programs, however, do not necessarily feature in a visually prominent way the images to which they initially responded. Do you think it is important that the images maintain centrality in the projects—or do you see them as something more flexible? Or, can you talk a little bit about how you see the role of the image archive as a resource for projects?

AB: One way the library continues to engage and surprise me is through the work that it generates. I realized very early on that if it was important to make the point that a book’s intended use is not its only use, then the same perspective should hold for the library as a whole. Though I was initially interested in the ways in which visual artists would use images in the collection, I suspected that these could encompass a wide range of approaches. Now that the library is being used as a springboard for non-visual works, that point becomes even more apparent and, I think, important. It’s very limiting to think that visual artists are the only kind of artist who use images as generative sources in their work. I know many writers who are highly visual. It’s a public collection; the last thing that I want to do is be prescriptive about who can use the library and how they should use it.

The online image collection serves two functions: it is a way to attach visual material to a book’s catalog record so that someone researching the collection remotely can get a sense of a book’s graphic content. But it also becomes a stand-alone resource in its own right. I think that Drafts is an ideal example of this—aside from Kaegan, I don’t think that a single person producing work for the series has set foot in the library! It’s amazing to me that the entire program has developed this way, and while I certainly encourage people to come to the actual space in Gowanus, I’m super happy that the website can generate events that engage with the library in such a substantive way.

See the Reanimation Library‘s website for more information. Drafts: Phase III will take place on Friday, May 10 at 6:30pm at The Drawing Center.