Curatorial Intern Gabriella Perez interviews New York-based artist George Venson about his wallpaper works, which combine drawing, painting, and installation mediums to challenge the juncture between fine art and design.

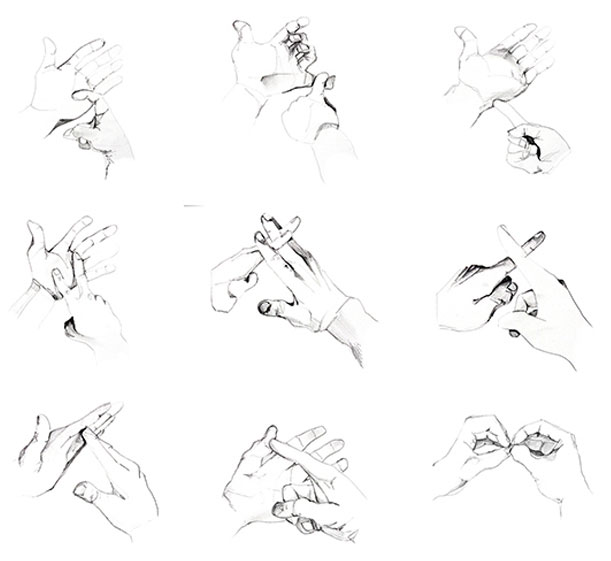

George Venson, Hands, white (detail), 2012. Nylon reinforced latex saturated wet strength paper and archival inks, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the artist.

Gabriella Perez: You first started designing wallpaper only a few years ago, in 2011. Can you describe your artistic practice prior to then? How did you arrive at wallpaper?

George Venson: Prior to 2011 I identified as a painter, but my paintings were designed as both drawings and sculptures: multi-panel screens with handles to fold and collapse, to be carried, stand on their own, or hang on a wall for viewing. I have always wanted to demonstrate the need to survive and remain mobile through my work. The year of 2011 was very frustrating: lost jobs, no money, no studio. Feeling unable to contribute, I was thus interested in becoming feral myself. So for one year during Occupy Wall Street I developed three street marches called Prototypes for the Dream (1.2.3). I now consider the videos of my street performances as paintings that require action. It was cathartic in retrospect, because I found a way to make something out of nothing.

I started thinking about drawing as sensual, free, and fun, which is what I would like people to think of when they see my wallpaper. I started sketching the raw human form with new friends in the design world, particularly illustrator Bruno Grizzo. While my artist friends were consumed by theory and trends, my designer friends had so much energy—but for commercial projects, such as magazine spreads, photo shoots, and illustrations. We would play dress-up and examine our work without heavy analysis. After I watched a movie on cave paintings it clicked—why not make hand drawn wallpaper like these installations in France! I could paint and draw on wallpaper for virtually no cost in very little space. I could then roll it up and travel like a salesman from house to house and cover large surfaces. Making original, handmade wallpaper felt subversive relative to commercial interior design, and yet it often appeals to decorators and others as very luxurious.

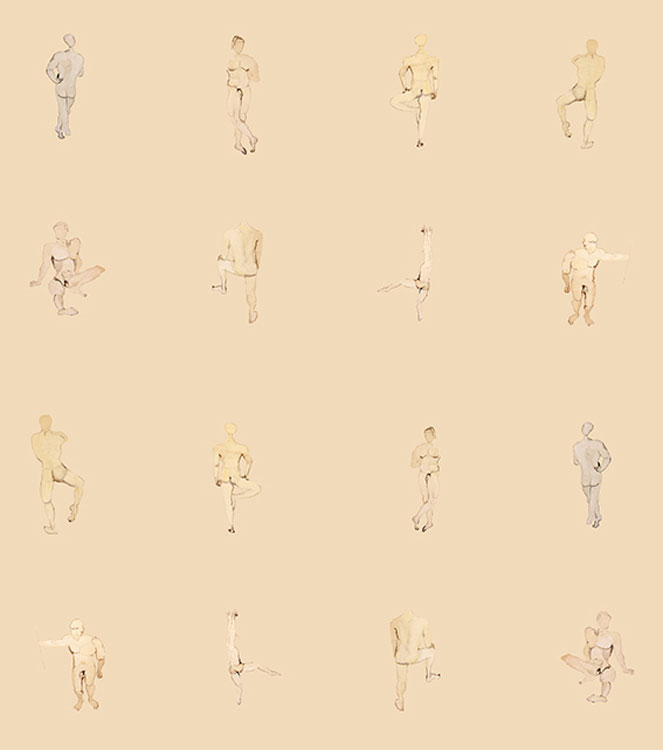

George Venson, Men, 2012. Charcoal, acrylic, and watercolor on wallpaper, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the artist.

GP: You have called your wallpaper both a “product” and a “conceptual skin,” suggesting that your work functions somewhere between a decorative commodity and a fine art object. Can you elaborate further on these designations?

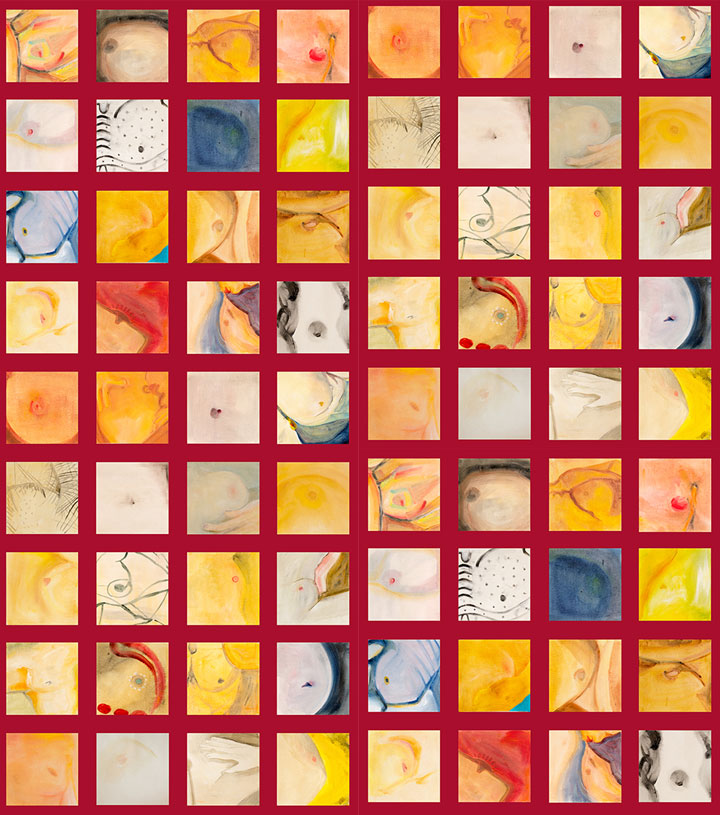

GV: The designations mean nothing to me, but are important for others. I can only say my clients view my work as both, sometimes one or the other, and sometimes neither. I like to think about wallpaper as a skin for the home (or store, hotel, etc.) rather than a paper. The paper I use for custom installations is very lightweight and nearly transparent, almost a bone tone. To call it a skin or underwear, suggesting the domestic container is a living thing, is interesting to me. I am very consciously addressing the historically domestic and decorative nature of wallpaper, and trying to do something opposite, something feral or institutional. This translates to choosing patterns or themes that are provocative when interpreted as wallpaper, especially within the context of wallpaper’s history.

My first collection referenced things like hands, ears, nipples, figures, and costumes, and later other things requested by commercial producers. Custom wallpapers give life to a room and there are no repeats, so this becomes a precious installation that gives a space an identity or an idea, rather than just a color or pattern. So far not one person has hung a painting on my wallpaper. There is some sort of tension there that I like; no one wants to give it scars. One time I was in an accident in my studio and blood splattered all over the paper and I thought for a second, good! It is no longer precious; it is alive.

George Venson, Unique mural commissioned by ASH NYC and installed in a Chelsea pied-a-terre (installation view).

GP: Your wallpaper is available as either hand-painted custom commissions or digital prints. How does your drawing practice inform each of these iterations?

GV: With wallpaper, the two layers of my business reflect two different approaches with respect to drawing. Hand-drawn commissions begin with architecture, scale, and preparatory diagrams. Each installation has no repeats so I must think about how the image of the wall will look and function with respect to the rest of the room, other walls, etcetera, as one continuous drawing. Paper in these instances merely becomes the tool with which I adhere my work to the structure beneath it. They are giant drawings and function as one body of interrelated pieces. Digital production requires the scanning and photographing of drawings, and then the creation of a pattern. The pattern becomes a contained drawing, so it is the opposite procedure: I make a small piece that can be flipped and repeated on a standardized paper endlessly to create a field of continuous imagery.

GP: Many of your designs are structured on a grid. Is this a nod to your twentieth-century predecessors or simply a formal organizational decision?

GV: The gridded arrangements allow me to organize my drawings. Hands, diamonds, people, and nipples are good examples. They allow the paper to function as a collection of independent yet equally important parts, as well as a collective, seamless population.

George Venson, Nipples, red, 2012. Nylon reinforced latex saturated wet strength paper and archival inks, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the artist.

For more information on Venson’s work, visit his website.